Tourmaline Quality Factors

One of tourmaline’s most sought-after and generally available colors is the pink/red variety known in the trade as rubellite.

Tourmaline's hue and depth of color can approach the range of ruby and pink sapphire. This 8.16-carat cushion-shaped rubellite and 10.78-carat emerald cut pink tourmaline are superb examples.

Green tourmaline’s pastel hues provide the market with pleasing alternatives to the deep, rich hue of emerald and the softer green of peridot. At their best, green tourmalines are transparent, brilliant, and clean, with attractive bluish green hues.Most green tourmalines are strongly pleochroic. Stones that show attractive colors in both directions—such as bright green in one and blue in another—are the most valuable.

Chrome tourmaline gems offer hues that are more saturated than most green tourmalines. Chrome tourmaline can be a lower-priced alternative to tsavorite or emerald. Both these gems are rare in sizes above two carats, but it’s not hard to find chrome tourmaline in sizes up to five carats. And, while tourmaline can’t match tsavorite’s luster or brilliance, it’s far less expensive than a tsavorite of equivalent size and quality.

Dark-toned stones—which are more common in the marketplace—aren’t very attractive. Some absorb light so intensely that they appear almost black from certain directions. Cutters typically fashion these stones with the table parallel to the length of the crystal. Gems cut this way might show a less attractive brownish or yellowish color through the crown. Dealers frequently describe these gems as “oily” or “olive” green. Their prices are much lower than the prices for fine green tourmaline or brighter bluish green tourmaline.

This 11.47-carat cushion-shape from Landanai, Tanzania, is a classic example of chrome tourmaline. Its high clarity, medium-dark tone, and strong green hue make it highly desirable.

This 8.76-carat emerald cut tourmaline’s medium tone and strongly saturated, slightly yellowish green hue make it very marketable.

High clarity, medium-light tone, and strongly saturated bluish green hue are the hallmarks of this 5.43-carat emerald cut tourmaline from Tanzania.

Blue tourmaline can range in tone from light to dark. The hue is often modified by green so you can have a blue color with just a little bit of green modifying color or a color that is very greenish but still blue. Some tourmalines have an even amount of green and blue to the color. Like green tourmaline the blue colors can be strong and vivid or less saturated and grayish.

This 1.80-carat rectangular step cut tourmaline from Russia is medium light in tone and has a slightly greenish blue hue with moderately strong saturation. This is a noteworthy combination for a blue tourmaline.

This 9.91-carat Afghan tourmaline hovers on the boundary between green and blue hues. Its high clarity and medium tone give it a pleasing appearance.

This 5.19-carat medium-dark, very strongly greenish blue emerald-cut tourmaline is from Namibia.

Since it was discovered in the late 1980s, Paraíba tourmaline’s striking neon blues and greens have electrified the gem world. The gem’s unique, vivid coloring instantly set it apart from other tourmalines. Initial worldwide reception to the gem was wild, especially in Japan, where demand for fine-colored stones was insatiable.Prices for this exotic newcomer—especially top quality in sizes between 3.00 and 5.00 carats—climbed rapidly to over $10,000 per carat. No tourmaline—even prized rubellite reds and chrome greens—had ever achieved such heights in value. Paraíba tourmaline’s rarity undoubtedly contributes to its high prices.

Fashioned Tourmaline can be found in large sizes. This magnificent stone weighs 45.31 carats and boasts natural, untreated color. Photo: Katharina Mint Ring © 2011 Fabergé Ltd.

The gem is an elbaite tourmaline that comes from one area of Paraíba state in Brazil’s northeast corner. Like many other Brazilian elbaites, Paraíba tourmaline forms in pegmatite. But researchers believe that its crystals form under very unusual conditions, with large amounts of trace elements like manganese and copper, which causes its color. Paraíba tourmaline is unusual because, although copper colors some other gems—notably turquoise—it’s not a coloring agent in any other tourmaline.In some specimens, there’s so much copper that inclusions of native copper—almost pure metal—highlight the gem’s interior. Scientists speculate that the native copper inclusions took shape in the early stages of cooling, after the gems started to crystallize.

Paraíba tourmalines appear in a range of greenish blue, bluish green, green, blue, and violet hues. Although buyers covet all these colors, blue and violet have the most appeal. Dealers use a number of names to try to capture the extraordinary quality of Paraíba tourmaline’s colors. Besides neon, they use terms like “electric,” “turquoise,” “sapphire,” or “tanzanite” blue, and “mint” green.

The Paraíba deposit revealed a range of new tourmaline colors unrivaled for their strongly saturated hues and light to medium tones. Representing the color range are a 2.59-carat turquoise-blue triangle cut, a 3.28-carat electric-blue pear shape, and a 3.68-carat green pear shape.

Overall, prices for the best Paraíba tourmalines easily surpass other tourmalines due to their more attractive hues, higher color saturation, and greater rarity. A direct comparison with other tourmalines makes the difference obvious. Compared to any other green tourmaline, for example, a green Paraíba tourmaline will have a more saturated hue and lighter tone.Because of the rough’s high value, Paraíba tourmalines are almost always custom cut. They’re usually faceted into brilliant cuts, commonly pear and oval shapes. You’ll rarely see Paraíba tourmaline in sizes bigger than one carat. With Paraíba, however, color is the key factor, not size. So if a dealer has to choose between a larger stone and a more vividly colored one—all other factors being equal—the gem with the better color is a better choice.

Copper-bearing tourmalines that resemble the vibrant, intense colors of the gems found in Brazil’s Paraíba region have also been found in other parts of the world. An article in the Spring 2008 issue of GIA’s Gems & Gemology scientific journal describes the copper-bearing gems of Mozambique. Nigeria has been a source of these striking gems as well.

During Paraíba tourmaline’s brief history, dealers have often resigned themselves to the gem’s extreme scarcity. However, new discoveries elsewhere in Brazil and eastern Africa present the possibility that viable, commercial sources of this rare copper-bearing tourmaline might one day supply the trade with more material. Unfortunately, the new sources also raise questions about the use of the term Paraíba to name these treasured gems.

The discovery of significant copper-bearing tourmaline deposits in Mozambique

increased availability and broadened the appeal for this gem. This 14.53-carat heated

gem is mounted in a striking pendant with black and red spinel, yellow sapphire, tsavorite,

and diamond accents. - Courtesy Carley McGee-Boehm, Carley Jewels

increased availability and broadened the appeal for this gem. This 14.53-carat heated

gem is mounted in a striking pendant with black and red spinel, yellow sapphire, tsavorite,

and diamond accents. - Courtesy Carley McGee-Boehm, Carley Jewels

Sources in Nigeria produce a vivid array of copper-bearing tourmalines. These stones range in size from 0.31 carat to 1.04 carats. - Courtesy Barker & Co.

Watermelon, bicolor, and multicolored zoning occurs when the trace elements change in concentration or composition during a crystal’s growth. Liddicoatite can show striking and complex zoning, and gems are often fashioned to showcase exotic color combinations. Gemologists describe these tourmalines as parti-colored.

This 11.21-carat bicolor tourmaline is a supreme example of both the gem material and the cutter's art. The stone has intense colors, a clean junction between the zones, and the highest clarity. - Lydia Dyer, gem courtesy of John Dyer & Co.

This Brazilian crystal is a typical watermelon tourmaline, with a pink core surrounded

by a thin green skin. The colors are best shown in thin slices, which are well suited to

one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces. - Courtesy Brasgemas

Sometimes tourmalines are color-zoned across the length of the crystal: A crystal that starts off as pink might end up with a green tip. Or they can be zoned parallel to their length, so that a red crystal might end up with a green overgrowth. Dealers call these watermelon tourmalines because their colors resemble the rind and flesh of that fruit. Designers sometimes exploit the look of watermelon tourmaline by setting slices of the crystal rather than faceting the rough.by a thin green skin. The colors are best shown in thin slices, which are well suited to

one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces. - Courtesy Brasgemas

Clarity

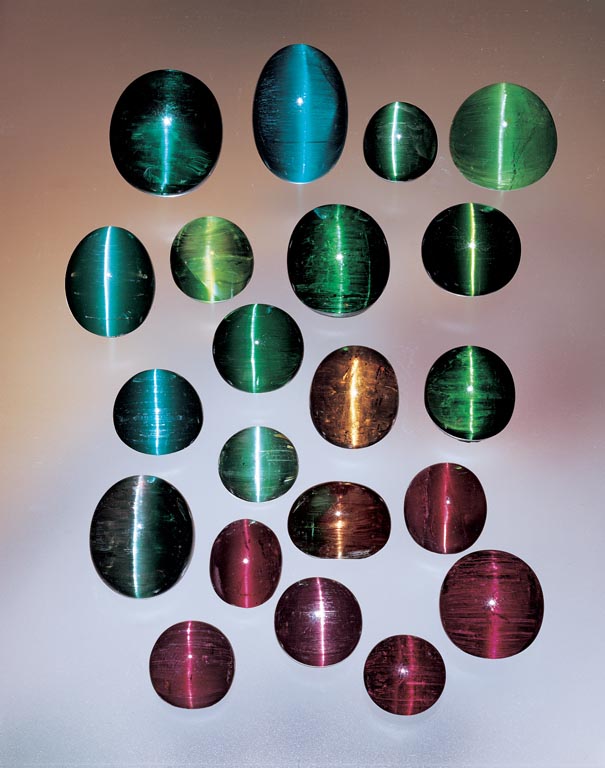

Colored tourmalines grow in an environment rich in liquids, and some of those liquids are often captured as inclusions during crystal growth. The most typical inclusions resemble thread-like cavities that run parallel to the length of the crystal. Under magnification, you can see that they’re filled with liquid or gas bubbles. Growth tubes—long hollow tubes often capped with minute mineral crystals—are also common tourmaline inclusions. If they’re numerous enough, and the rough is correctly cut, they can cause a cat’s-eye.

The gems in this remarkable suite of cat’s-eye tourmalines are all from Brazil. Inclusions

cause the cat’s eye effect and add value. - © GIA and Harold & Erica Van Pelt

Dealers usually tolerate red tourmalines with some eye-visible inclusions as long as the color is strong and attractive. Inclusions that reach the surface interfere with luster and polish and make gems harder to sell. And although liquid inclusions are less visible in stones of intense color, stones with prominent whitish inclusions—no matter how vibrant the color—are undesirable.cause the cat’s eye effect and add value. - © GIA and Harold & Erica Van Pelt

Inclusions are much more visible in gems with light tone and low saturation. Since these stones don’t have strong and attractive color to compensate for the inclusions, most buyers reject the ones with eye-visible inclusions. Many included tourmalines with good color are cut as cabochons to emphasize the color and minimize the appearance of the inclusions.

It’s not unusual for pink and red tourmalines to have eye-visible inclusions. Unless their size or the number of the inclusions is distracting, knowledgeable consumers consider the color to be the dominant value factor. Green tourmalines are expected to be free of eye-visible inclusions so distracting inclusions can lower the value of the green gems. For the other colors, tourmalines with no eye-visible inclusions are more valuable than those with inclusions that can be seen. The more visible any inclusions are, the more the value drops.

Cut

The elongated shape of many tourmaline crystals has a direct impact on the finished gem’s shape and proportions. As a result, there are many narrow, non-standard sizes available. Although some are very attractive, many gem buyers prefer stones with standard dimensions because they’re easier to set in standard mountings.

Jewelry designers create custom mountings to accommodate the shape of fashioned tourmalines. - © GIA & Tino Hammid, courtesy Chris Almquist

Cutters often fashion tourmalines as long rectangles. Making the cut parallel to the length of the rough crystal helps to reduce waste. But cutters also have to consider tourmaline’s optical properties.Tourmaline is strongly pleochroic, which means that it can show different colors in different crystal directions. One of tourmaline’s pleochroic colors is typically much darker than the other. In addition, many tourmalines absorb more light down the length of the crystal than across it. So a crystal that appears pale green across its length can be very dark green—sometimes almost black—when you look down its length.

Rather than cutting every tourmaline lengthwise, many cutters orient a fashioned gem based on its depth of color. To darken pale rough, they might orient a gem’s table so it’s perpendicular to the crystal’s length. To lighten dark rough, they orient a finished gem’s table so it’s parallel to the crystal’s length.

Carat Weight

Fashioned tourmalines in larger sizes rise considerably in per-carat price. Even though specimens can reach spectacular sizes, these are rare. Availability drops and prices rise sharply for facet-quality rough material. For fashioned gems of similar color and clarity, the price per carat generally increases as the gems pass the five-carat milestone.

Large tourmaline crystals are often fashioned by gem sculptors into special pieces for clients looking for the unusual. Renowned Idar-Oberstein gem cutter Bernd Munsteiner fashioned this 11.18-carat blue-green gem in his unique style.