The Stories Behind the Photos: A Gigantic Aquamarine and ‘Gaudy’ Nature

July 28, 2020

Robert Weldon has traveled the world in pursuit of the most fascinating and beautiful gemstones as a gemological photojournalist. He has climbed into mines, trekked miles to the next location and waited patiently for the perfect light. He is as enthralled with the people who mine and deal with gemstones as he is with the places and cultures where they are found.

Weldon has traveled to some of the world’s major gem sites, including Burma, India, East and South Africa, Colombia, Bolivia, Brazil, Russia, and several other gem sources. His photographs are published in scores of international gemological, jewelry and consumer publications, illustrating his own and other authors’ articles, and in several books. They have also appeared regularly on the cover Gems & Gemology since 2008.

Every one of Weldon’s photos has a story to tell — whether it is how he conceived the image, how he chose to show the gem at its best, or how he decided to show the context of the locality where the gem was found. Over the course of three decades, he has photographed some of the world’s most important gems and jewelry.

He combines art and gemology in a way that makes us even more appreciative of what we see.

“The industry that we are all a part of and love so much is very much a visual one. Everything really relies on our senses, but particularly our eyes and what we see and feel,” he says. “On the basis of a good image we often make decisions in an instant that transfer millions of dollars across the world.”

Here are some of his favorite gem stories.

Don’t Make a Habit of This

Weldon was given the opportunity to photograph the 10,363 carat (ct) Dom Pedro Aquamarine, a 14-inch tall obelisk carved by master gem sculptor Berndt Munsteiner, at a Tucson show more than 20 years ago.

Unable to fit it into his small portable studio, he and gem dealer Evan Caplan decided to take it out to the desert. They placed it carefully on a rock with the iconic Mission San Xavier del Bac serving as the backdrop. The ancient mission, constructed between 1783 and 1797, juxtaposed against this modern, angular gem sculpture, created a dramatic image.

“Evan crouched inches away, ready to dive for it — and save it — as it swayed slightly in the breeze,” Weldon recalls. They got the shot and spirited the sculpture to safety in Caplan’s booth.

Months later, Munsteiner marched towards Robert, who was “transfixed, mortified and scared” as the legendary carver approached him.

Then he beamed. “Robert, that was a great picture,” he said. After a pause, he added: “By the way Robert, do you know what the value of this stone is?”

Luckily, the photo was a success and was featured in JCK magazine; Munsteiner says a copy hangs in his living room.

“This is something you should never do! It is much too dangerous and too much of a risk,” Weldon says. “Never, never would I do that again.”

The Dom Pedro is “the largest single piece of cut-gem aquamarine” according to the Smithsonian Institute, where it has been on display since 2012. It so breathtaking that the Smithsonian said it is “one of the few objects in the world that can hold its own in a display case just 30 feet from the Hope Diamond.”

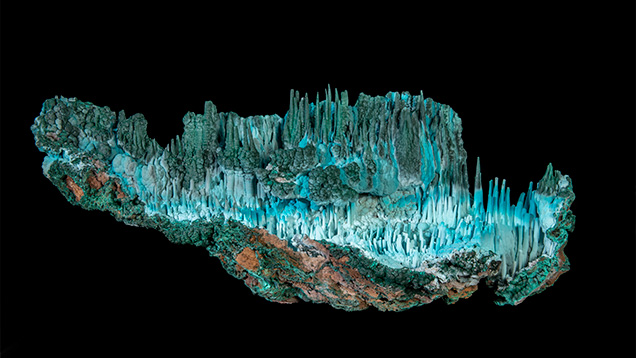

A Stunning Stalactite

This malachite and chrysocolla specimen, found in a cave in the Congo, weighs 80-90 pounds and is a meter and a half in length.

“Interestingly, it is on display upside down. But we didn’t want to photograph it [or display it] the way it formed in nature, because such positioning would break those beautiful stalactites,” Weldon says.

The GIA Museum acquired this “stunning” malachite and chrysocolla specimen at the 2020 Tucson shows. It has been nicknamed “Atlantis” for its resemblance to the exotic underwater realm. See a video presentation and explanation of its formation.

If you look closely, you may see a small hole in the center of each stalactite. Solutions dripped though these straw-like tubes and caused the downward growth of the stalactite. If a tube opening was not there, the solutions ran down the outside of the stalactite, making them thicker.

Stalactites normally develop under the influence of gravity and should form straight growth. Some of the stalactites in this specimen are oddly curved and bulbous, which suggests an outside influence such as air or water currents that caused more growth on one side.

“You really begin to understand the formation of gemstones just by looking at this. You can see how drip by drip mineral-rich waters gave rise to those colorful stalactites and this is what you see today,” Weldon says. “It is a spectacular display of how only nature can be as gaudy as this. Wow, what a piece — it’s just absolutely stunning.”

Watch a GIA Knowledge Session where Director of the RTL Gemological Library Robert Weldon, Senior Manager of Research Dr. Aaron Palke, and Supervisor of Field Gemology Wim Vertriest offer an exclusive look at GIA field gemology expeditions through previously unpublished photographs.

Amanda J. Luke, a senior communications manager, has been an editor and writer at GIA for 19 years.