Sapphire Mining Along the Upper Missouri River

The washing plant was fired up early in the morning, and the miners were all busy working. Cass Thompson, owner of Eldorado Bar mine, greeted the GIA team and introduced the history, the mining, the people, and the sapphires from this part of the Missouri River. GIA’s gem testing lab purchased a mine run in order to enrich the research sample collection with more Montana sapphires.

BRIEF HISTORY

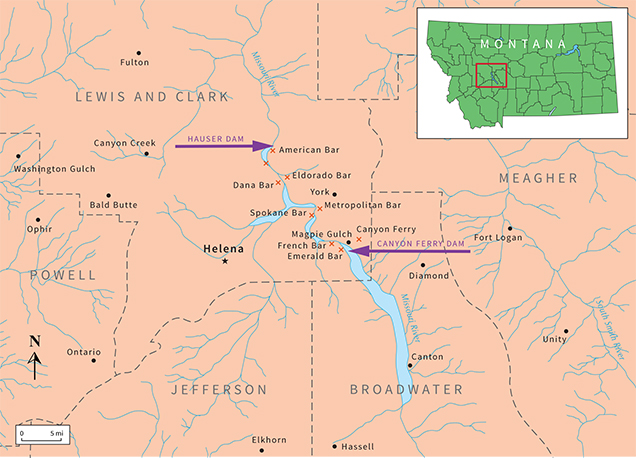

About 30 miles northeast of Helena, on the Upper Missouri River, is one of the main sapphire mining areas in Montana. These sapphire deposits include a series of terrace-like gravel bars along the riverbank. The discovery of sapphire here in 1865 was the earliest in the state. These gravel bars were once underwater, but erosion gradually cut the canyon deeper, and now the river is bounded by the gravel bars.

Sapphire has been reported from several of the gravel bars. Eldorado Bar is the most actively mined deposit even today. Some historical sapphire mining operation relics from the 1800s can still be seen. Rock hounds, jewelers, mineral collectors—anyone—can dig sapphires by paying a fee to the mine owners. This is now one of the best tourist attractions in Montana.

Sapphires from the Upper Missouri River gravel bars were first found as heavy crystalline stones accumulated in the sluice boxes of gold miners. They were not officially introduced to the public until 1873, when Dr. J. Lawrence Smith published an article on them in The American Journal of Science. He described the morphology of the sapphires and pointed out that the richest gravel was in the Eldorado Bar region.

miners built is still partially exposed. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

The corundum is found scattered through the gravel (which is about five feet deep), and upon the bed-rock…It is most abundant upon the Eldorado Bar situated on the Missouri River about sixteen miles from Helena; one man could collect on this bar from one to two pounds per day…My opinion is that this locality is a far more reliable source for gem variety of corundum than any other in the United States I have yet examined.

Large-scale mining in the Upper Missouri River region did not start until 1891. A British syndicate called the Sapphire and Ruby Company of Montana commenced mining operations on some of the richest gravel bars at that time, including Eldorado Bar and French Bar. Even though the company had broad support from the British wealthy class, the lack of demand forced it to close a couple years later.

bluish, greenish, and yellowish colors most commonly seen in Eldorado Bar. Photo

by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

In 1938 Owen Perry and John Schroeder took over the mine. A market was readily available owing to the demand from manufacturers of heat-resistant precision bearings for gyroscopes in bombsights and torpedoes required for defense purposes. This kept the operation running through most of World War II, until the introduction of synthetic sapphire in the mid-1940s. The current owner’s family purchased the land in the 1950s and has actively mined it since then.

CURRENT MINING OPERATION

Today the Thompson family runs two mining operations along the Upper Missouri River: Eldorado Bar and Spokane Bar. Eldorado is still the main focus, and mining usually lasts the whole summer. Mining occasionally takes place in winter, but it is not the main source of revenue.

From a cross-section exposed by digging, the sapphire-bearing gravels are clearly visible above the brownish shale bedrock and below a volcanic ash layer of various thicknesses. The thickness of the gravel layers is about 20 feet at this location. Due to the alluvial nature, pebbles are relatively well sorted in the gravel layer. Along with sapphire, topaz, hematite, gold, and fossils can also be found in the gravel. The miners recover as much as they can from the jig at the end of the day. While sapphire is the main target, byproducts like gold also help cover costs.

The Eldorado Bar operation is completely mechanical. Bulldozers are used to dig the open pits and transfer materials around the site. Freshly mined gravels are screened by a grizzly (a metal grille) to remove blocks larger than 2.5 inches. These bigger blocks can easily wear the sapphire-washing equipment and increase mining costs. Materials that pass the screening are fed to the washing plant for processing.

The on-site washing plant includes a trommel, a conveyor belt, and a pair of jigs. The plant can wash about 80 cubic yards of material within four hours. The mine run that the GIA lab purchased was from this amount of gravel. The rotating trommel works as a scraper and screen to clean the gravels and remove the waste. Then sapphire-bearing gravels with proper size range go to the jig. The jig works as a gravity separator with the help of water. Sapphires are concentrated toward the bottom of the jig. The water that supplies the washing plant is from the Missouri River and is recycled as much as possible.

Cass Thompson and his family always keep the environment in mind. To maintain the beauty of the area, the miners make sure to restore the land after mining. They do not exploit the deposit because they wish to leave enough resources for future generations.

HARVESTING

At the end of the day, the most exciting moment for every party is cleaning the jig. The miners, together with the GIA team, recovered as many sapphires as possible from the jig. The rest of the gravel was packed in multiple buckets for the team to take off-site for more detailed searching. Everybody enjoyed the excitement when big stones were discovered in the jig. The smiles on the miners’ faces mirrored our experience at Eldorado Bar.

The GIA team went through the rest of the material on a light table at Fine Gems International’s office in Helena.

THE STONES

Sapphires from Eldorado Bar have a larger size range than stones found in other sapphire mines in Montana, according to Cass Thompson. The most common colors are greenish blue and bluish green. While the whole spectrum of colors has been recovered from this mining site, stones with green and blue hues are the majority. While these stones have better size and clarity, they do not react well to heat treatment.

A total of 1,045.05 carats of sapphire was recovered from this mine run. The largest stone weighs 16.776 cts., and there is a pink stone weighing 7.858 cts. All these stones are now in the GIA corundum collection in Carlsbad.

BUSINESS MODEL AND FUTURE

According to Cass Thompson, the overburden at Eldorado Bar is relatively thin compared to some other sapphire-bearing gravel bars, which makes mining in Eldorado Bar profitable and others not. Several factors are critical for sapphire mine owners to carefully consider when starting a mining operation: fuel cost, labor cost, machine maintenance, overburden thickness, water resource, and readily available market are the major ones. Whether a mine is profitable is determined partially by its nature and partially by the business model.

Like many other sapphire miners in Montana, the Thompson family now directs the Eldorado Bar operation more toward the tourist market. Ninety percent of the mining and business is done during the summer months. Their store offers the visitors paid gravel washing and carries inventory such as rough sapphires, mineral specimens, and some jewelry. The majority of the sapphire production is offered to the tourists. Gravel washing and mine run are the two main channels the rough sapphire is sold through. Purchasing a mine run means that the client will receive the production of a full day’s work.

As the third generation in the family business, Cass Thompson now runs it. He and his father still enjoy talking about the early days of his mining career, when he was a kid. From their conversation we could see the pride they hold for their beautiful family, the land, and the sapphires.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology. Andrew Lucas is manager of field gemology for education, Shane McClure is global director of colored stone services, Nathan Renfro is analytical manager of the gem identification department and analytical microscopist of the inclusion research department, and Kevin Schumacher is digital resources specialist at GIA Carlsbad.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors would like to thank Robert Kane, CEO of Fine Gems International, for arranging this visit, and the staff at Eldorado Bar. Thanks also go to Mr. Jonathan Muyal, Research Stone Collection Gemologist at GIA Carlsbad, for preparing the stones and taking sample photos.

Smith, J. Lawrence. (1873) Notes on the corundum of North Carolina, Georgia, and Montana, with a description of the gem variety of the corundum from these localities. American Journal of Science, Series 3, Vol. 6, pp. 180–186.

Mumme, I. A. (1988) The World of Sapphires. Port Hacking, New South Wales, Australia: Mumme Publications, pp. 112–118.