The Lure of American Freshwater Pearls: Revisiting the Latendresse Family

May 18, 2017

In 1987 Dr. E. J. Gübelin visited John Latendresse and his pearl farm in Camden, Tennessee. The following year GIA Education sent a team to visit the Latendresse family to witness and record the development of the American freshwater pearl industry. The valuable information and photographs obtained became part of GIA’s pearl course and a good reference for both the Institute and the trade. In June 2016 a GIA team revisited the Latendresse family. For more details about this trip and a pearl industry update, please see the article “Freshwater Pearling in Tennessee.” During this trip the team collected Tennessee River freshwater mussels, interviewed the Latendresses and took the opportunity to investigate the American freshwater pearl industry. They were also very fortunate to look at the family’s large and remarkable pearl collection.

daughter, Sabrina. Three generations of the Latendresse family work together to keep

the American pearl legacy going. Photo by Tao Hsu/GIA.

THE LATENDRESSE FAMILY

Like Mikimoto is connected to the Japanese cultured pearl industry, Latendresse is to the modern American pearl industry. John Latendresse was the one who first stepped into the pearl business. The father of American cultured pearls, he was also referred to in the gem and jewelry trade as “the Picasso of pearls.”

John Latendresse, born in South Dakota in 1925, left home at 13. He eventually became a very passionate and influential self-taught leader and educator in the American pearl industry. In 1949 he moved to Tennessee, where divers typically brought their pearl findings to buyers. At that time all pearls found in American waters were natural, byproducts of the more profitable mollusk shell business. He started his natural pearl collection by buying the discoveries of divers from Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Kansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin.

John settled in Camden, a small town next to Kentucky Lake in western Tennessee with a rich pearling history. Kentucky Lake formed after the construction of the Kentucky Dam from 1938–1944. The land that was flooded was once farmland and provided more than enough plankton to support the freshwater mussel growth. With the increasing mussel shell demand from Japan after World War II, John formed the Tennessee Shell Company, Inc. (TSC) in 1954. The business brought him fortune and the opportunity to be involved in the pearl industry.

By the early 1990s the company processed and shipped about 5,000 tons of shells to Japan annually, about 45% of the total amount exported from the United States. The shells were processed in Japan to become nuclei in cultured pearls. While selling mussel shells and importing cultured pearls from Japan and China, John was challenged by his Japanese colleagues, who told him that he could never culture good-quality pearls in America. An adventurous and curious Southern boy, John accepted the challenge and successfully conquered the related difficulties. John spent the rest of his life researching, experimenting, marketing, and promoting American freshwater cultured pearls.

John’s wife, Chessy, is a Japanese woman who supported him wholeheartedly in his pearl culturing experiments. Chessy’s mother was a certified gemologist and worked in Japan’s pearl industry. Chessy was a well-trained pearl stringer, but she was not very familiar with pearl culturing while in Japan. Later, in order to support her husband, she learned the culturing technique, translated numerous materials, became the head technician at the Latendresse pearl farm, and trained many local young people to be Technicians. Today she still strings pearls both as a hobby and for the family business, which according to her is the best way to relax.

to learn pearl culturing techniques so she could use them on American mussels. Photo

by Artitaya Homkrajae/GIA.

As a loving mother, grandmother, and cofounder of the family business, Chessy has witnessed the entire history of the American cultured pearl industry. She passionately shared her experience and knowledge with the GIA group. She would like to teach more young people the skills of pearl culturing and stringing.

Of Chessy and John’s three children, Gina Latendresse and Renee Latendresse have been highly involved in the business. Gina now runs the pearl business, American Pearl Company, in Nashville. The company was founded by her father in 1961. After John passed away in 2000, the family stopped their pearl culturing operations. Today Gina has downsized the business to four people including her and focuses on selling pearls and pearl jewelry. The business supplies loose pearls to retailers and jewelry designers as well as its own pearl jewelry to retailers. About 80% of sales are from the family’s natural pearl collection.

Gina grew up in the pearl business and is grateful that her father taught her so many things about pearls and passed on the pearl passion to her. She is also a very active educator and has traveled all over the country and the world to give presentations about pearls and promote American natural pearls. The Latendresse family has always been very supportive of pearl research by gemology laboratories, including GIA. Our wonderful research trip was made possible by the support and help of the Latendresse family, especially Gina.

FRESHWATER PEARL CULTURING IN TENNESSEE

It is not the pristine clear blue waters of Tahiti with half-naked women diving for pearls; rather it’s the muddy rivers of Tennessee. A little bit less romantic, but maybe more intriguing.

When John Latendresse accepted his Japanese friends’ challenge in the early 1960s, he probably did not realize that he would spend the next two decades searching and experimenting. Although natural pearls had been recovered by Native Americans in many water bodies in North America, culturing had never been attempted before.

The first critical problem was to find the ideal bodies of water for the farm. Although freshwater mussels are some of the most long-living organisms on earth, they are extremely sensitive to their living environment. John and his colleagues tested more than 300 bodies of water all over the country. More than 20 factors were evaluated, such as temperature, pH level, and local climate. Surprisingly, all tests proved that the reservoirs next to John’s home in Camden were the ideal locations.

Experiments were started in small water bodies, including a lake on the Latendresses’ land in Camden. Gina described the experiments they did here. Due to the lack of plankton, it was difficult for the mussels to get enough nutrients to survive. At the same time, they also experimented on tissue and bead nucleation of different mussel species. Chessy played an important role in transferring the Japanese techniques and researching the unique techniques applied to the American mollusks. In 1966 she returned to Japan to observe the nucleating process. She realized that many of the problems of nucleating American mollusks came from the biological makeup of the American species compared to the Japanese species. Therefore techniques needed to be developed specifically for the American freshwater mussels.

for culturing. Photo from the Edward J. Gübelin Collection.

In 1982 the pearl farm was established at the Birdsong Creek location on Kentucky Lake. This location met all the requirements of a pearl farm. The Latendresses negotiated with the Tennessee Valley Authority to gain a lease for exclusive use of this part of the lake. After 20 years of effort, the family harvested their first commercial pearl crop in 1983. John Latendresse had realized his dream of growing pearls in America as pristine as those in Japan and other countries. He continued to experiment with culturing different shapes of pearls and successfully marketed them to domestic and international customers.

even with these dry mussels. Each net can hold about a dozen mussels. Photo by Tao

Hsu/GIA.

a little cup on the top of each stick to hold the bead. Different holders are for beads of

different sizes. Photo by Tao Hsu/GIA.

As C. Richard Fassler described in 1991, “There were several hundred PVC pipes, each 40 feet long, lying parallel in rows, covering 9 acres. The pipes support nets which can hold up to a dozen mussels.” The nets were hung below the pipes with an optimistic distance between. The farm used mainly washboard mussels (Megalonaias nervosa) to culture pearls. Our diver and river guide on the tour, Don Hubbs, recalled that the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) allowed the Latendresse family to harvest 75,000 washboard mussels of 3 to 3.5 inches to use in pearl culturing each year. This was a special permit as the size was below the lower limit for commercial shell harvesting. Smaller mussels are younger; therefore they can secrete mother-of-pearl more quickly than older mussels. John Latendresse successfully demonstrated the technique and expertise of pearl culturing to gain the permit and license for the operation.

From 1983 to 2000 the pearl farm produced freshwater cultured pearls. Each year John saved about 20% of the harvest for the family collection. This is the pearl trading business’s main inventory that keeps the legacy going. After John passed away in 2000, the farmed stopped its commercial culturing operation. The farm was sold to its current owner, Robert Keast, who transformed it into one of the top tourist attractions in Tennessee. A small section of the pearl farm was maintained and is mainly used to demonstrate pearl culturing to visitors.

THE UNIQUE AMERICAN CULTURED PEARL

John Latendresse is called the Picasso of pearls because he used different shapes of beads in the mussels and cultured his unique fancy-shaped pearls. The culturing technique John used bridged the techniques used by the Japanese and the Chinese. He had plenty of resources to produce his own beads from the same species of mussels used to culture pearls.

John also started with culturing blister pearls, the simplest among all shapes to grow. He admitted that perfectly round pearls are the hardest to culture. He then opened the door to a completely new category of cultured pearls by inserting different shapes of beads into the mollusks, which involved technical difficulties. The fancy-shaped beads usually have some sharp corners and edges in comparison to round or flat beads. This increased the rejection rate and the mortality rate of the mollusks. Special skills and care were taken to culture these pearls.

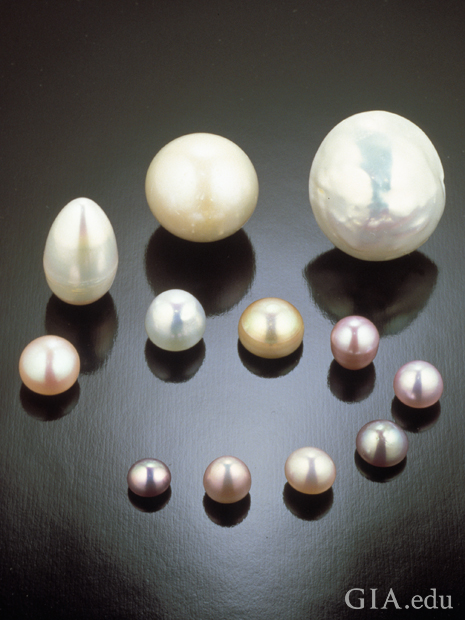

Shapes of American cultured pearl varieties include the Domé Pearl (cultured blister pearl) and fancy-shaped cultured pearls. Fancy shapes include the coin, rectangular, triangular, cabochon, marquise, teardrop, and navette. Some of the deep lavender cultured blister pearls from the pink heelsplitter mussel are spectacular. Many of these shapes are so unique that they can be used as an indicator for pearl identification.

American cultured pearls are mainly of white and silver bodycolors with a rainbow of overtone and nice orient. Less than 2% of each harvest is of blue or golden bodycolor. These rare colors may be related to mollusk condition, water quality, and other variables.

American cultured pearls have a wide size range, from 1 to 2 mm up to 30 mm. The coin-shaped pearls are usually 10 to 15 mm, and the navette shapes 10 to 30 mm. To better control the quality, the blister pearls were cultured for at least 18 months to two years, and the fancy-shaped pearls from three to five years. A period of three years can generally guarantee 2 mm of nacre.

THE REMARKABLE LATENDRESSE NATURAL PEARL COLLECTION

Although John Latendresse spent over three decades realizing his dream of culturing pearls, he never stopped collecting natural pearls from American rivers and lakes. His American natural pearl collection is the world’s largest. Some of its top items were once on display at the American Museum of Natural History. With natural pearl resources reaching exhaustion all over the world, this world-class collection is even more precious now. We were very fortunate to be able to see these natural pearls.

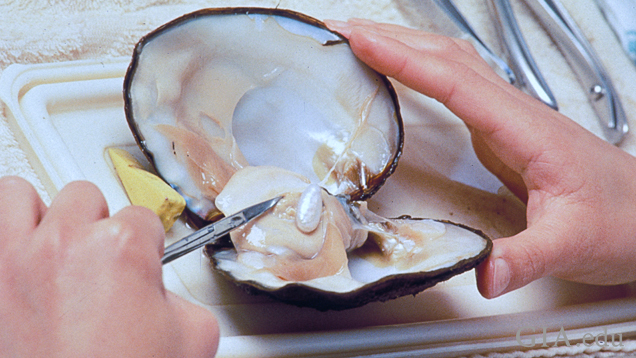

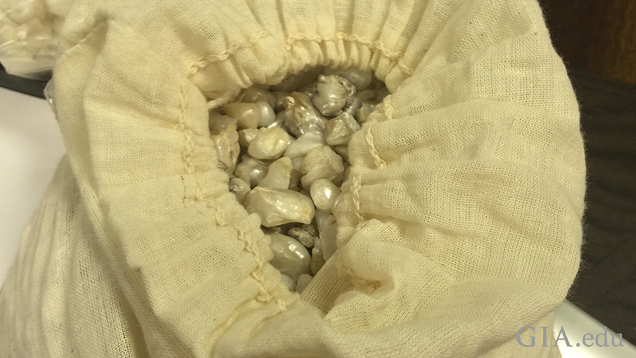

Gina selected representative American natural pearls from the collection to show us. She began with a jar of natural pearls she had purchased from a diver. According to the diver, he had recovered these pearls throughout his entire diving life. Gina said that this was a typical method for her father and the family to purchase natural pearls.

The significant items in this collection all have their own stories. Gina still remembers vividly that her father would pick up a pearl from his collection and tell her where he attained it and what was special about it. Chessy told us that all these pearls were his babies and he memorized every detail of them. Like father, like daughter—Gina inherited the passion and love of pearls, and dedication to the pearl business, from her father. She grew up surrounded by pearls. She looked at them, touched them, and sorted them.

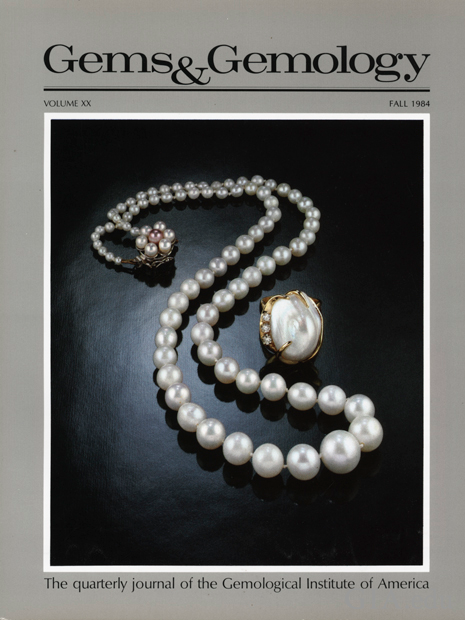

Of all American natural pearls, round and/or near-round are the rarest, accounting for less than 0.01%. A graduated strand of round pearls gathered from the Tennessee River over a 25-year period caught our attention immediately. This strand is precious and unique, the best demonstration of how rare natural round pearls can be. It was featured on the cover of the Fall 1984 Gems & Gemology containing John and James Sweaney’s article about the American pearl industry. Gina and Renee each wore this strand at their weddings.

natural pearl ring from the Latendresse family’s pearl collection. The strand took John

25 years to put together and was also featured by National Geographic in 1985. Photo

by Tino Hammid/GIA, courtesy of the Latendresse family.

Next to round and near-round, symmetrical shapes in natural pearls are hard to find. The collection put together over half a century has only a limited amount of them. The chance of finding a natural pearl of any sort in a mussel shell is about 1 in 10,000, and only a tiny fraction (estimated at less than 5%) have symmetrical outlines, such as button, pear, and barrel.

Photo by Tino Hammid/GIA, courtesy of the Latendresse family.

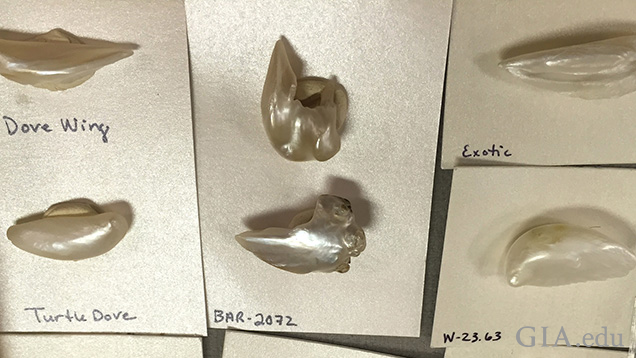

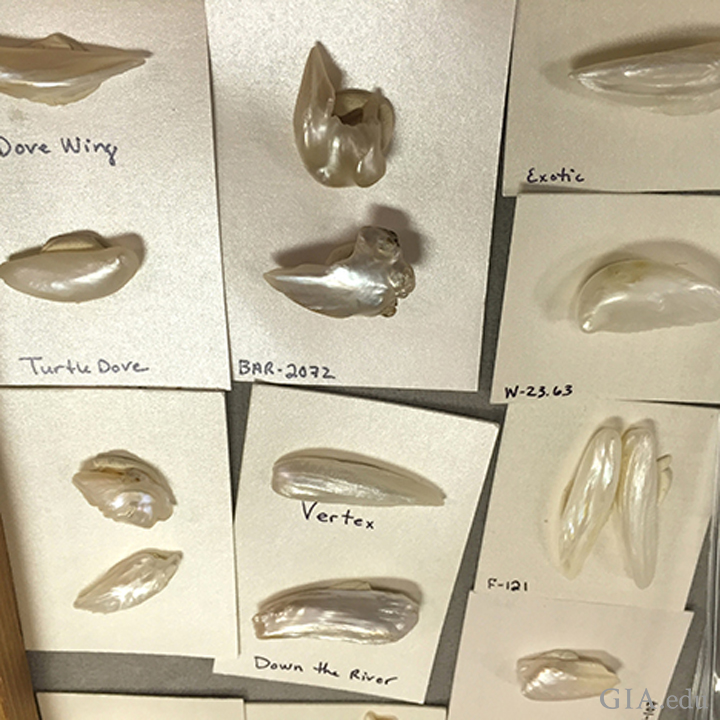

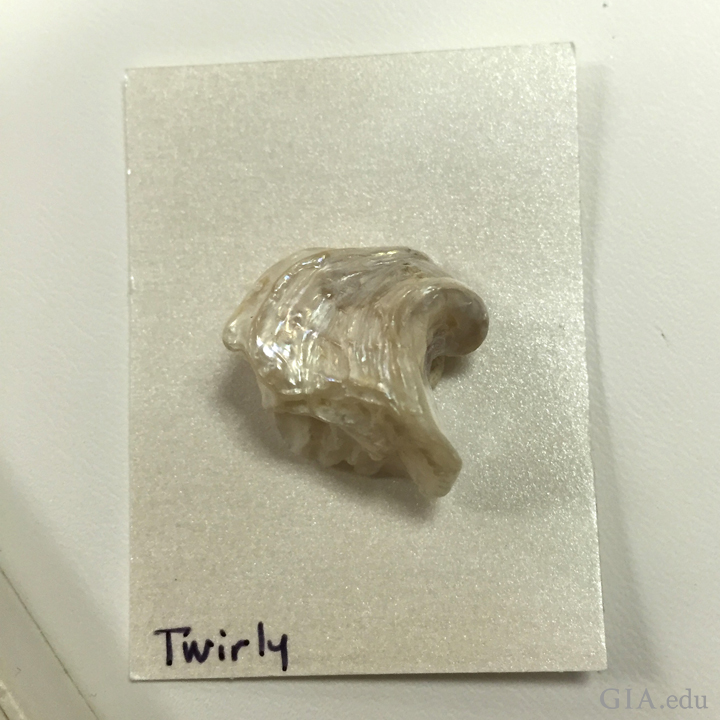

Other than the round, near-round, and symmetrical shapes, American natural pearls are mostly baroque shapes. Each baroque pearl is different, but some can be sorted into categories based on appearance. Among these baroque shapes, “wings,” “petals,” “rosebuds,” “turtlebacks,” and “snails” are commonly found. Their appearances match their names very well.

Wing pearls do look like bird wings. A rare pair of wing pearls is perfect for designer jewelry. The snail pearl is another interesting category. An X-ray of a natural snail pearl recovered from Indiana revealed a tiny snail (1985 National Geographic article). The Latendresse collection contains some magnificent wing pearls and snail pearls. The largest wing pearl in the collection is over 7 cm long. The two largest snail pearls are 89.93 and 80.43 cts., with white and fancy bronze lavender colors, respectively.

Some other large baroque-shaped natural pearls are so unique that they can hardly be sorted into categories. These are some of the best natural baroque-shaped pearls that jewelry designers can source on the market.

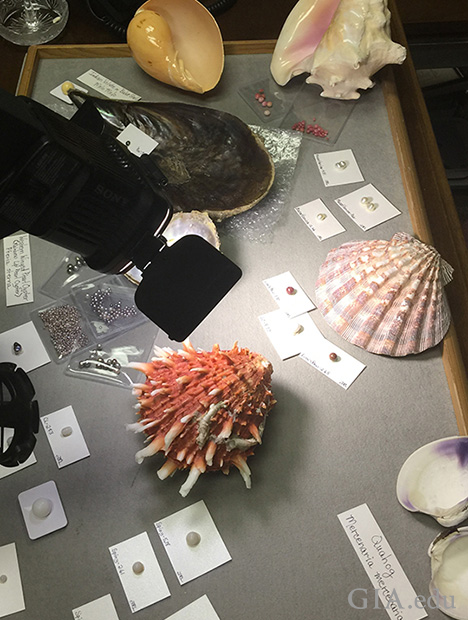

The collection contains saltwater natural pearls as well. Gina put together a display of oyster and snail shells with the corresponding natural pearls, including the largest natural abalone pearls we had ever seen. There were pen shells, quahog, Melo melo, spiny shells, horse shells, and more. Gina traveled the world to collect all these natural pearls and shells, even handpicking some of them during vacations.

oysters. This is also part of the collection. Photo by Tao Hsu/GIA.

While we were all amazed by the natural pearls presented, Gina reminded us that she had pulled out only a small fraction of the whole collection, which can literally fill a room. She showed us some vintage bags full of natural pearls that had not yet been sorted. All the bags were handmade by Chessy decades ago. We finally understood the size of the collection is and why American natural pearls still circulate on the market.

The unique American pearl, natural and cultured, provides some of the best materials for jewelry designers all over the world. Their exotic shapes and top-quality colors and lusters can fit into all different designs. The American Pearl Company still focuses on supplying natural and cultured American pearls to large retailers such as Tiffany and Mikimoto, as well as jewelry designers. Although the company also sources pearls from other countries, the family collection’s inventory is still the majority. Gina also designs and manufactures pearl jewelry and a leather jewelry line.

In addition to pearl trading, being a pearl educator is an important part of Gina’s life. She gives lectures to trade organizations, schools, and other interested groups. Like her father she believes in the power of education. To facilitate her teaching, she put together a display collection that she affectionately calls “Pearl Circus” for demonstration purposes. She cut open natural and cultured pearls to show students and consumers their internal growth patterns. She feels that educating the public is one of the best ways to popularize American pearls and attract customers.

EPILOGUE

With the help of the Latendresse family, especially Gina, our Tennessee pearl trip resulted in rich information, high-quality research samples, and precious memories. Pearl, the queen of all gems, symbolizes purity, refinement, glamour, and wealth, but it can only reach people’s hands through hard work and persistence.

John Latendresse’s American pearl dream came true after 20 years’ hard work. Three decades have passed since the Latendresse family harvested their first crop of American cultured pearls. During this time the global pearl industry experienced dramatic changes. The Latendresses still hold tight to their pearl dreams and further John’s legacy with the pearls he spent his whole life collecting. To most Americans these pearls are gems that they can be proud of; to the Latendresses, they are more like family members. We truly felt the love of pearls and hope that this American pearl legacy is passed to future generations.

freshwater natural pearl in 14K gold. Photo by Tino Hammid/GIA, courtesy of the

Latendresse family.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology at GIA Carlsbad. Dr. Chunhui Zhou is pearls research scientist and manager of pearl identification in New York. Artitaya Homkrajae is a staff gemologist at GIA Carlsbad. Both Joyce Wing Yan Ho and Emiko Yazawa are staff gemologists at GIA New York. Pedro Padua is video producer at GIA Carlsbad.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors would like to thank Gina Latendresse for her support of this trip and help in the field. They also highly appreciated the guidance and help of Don Hubbs from Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

Fassler C. R. (1991) “The Return of the American Pearl.” Aquaculture Magazine.