M.D. Hohenstine’s Gem Displays: The Process of Creating Popular Window Art with Loose Gemstones

April 27, 2018

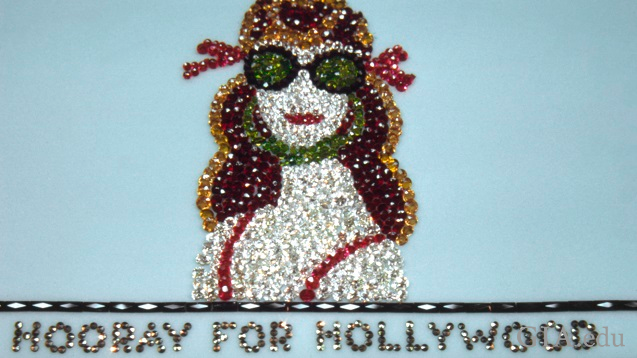

Editor’s Note: Jeweler M.D. Hohenstine’s spectacular window displays were a beloved tradition in downtown Columbus, Ohio from the 1920s until his death in 1976. The displays, consisting of hundreds of loose, natural gemstones arranged into a variety of shapes, patterns and figures, were changed every other week. Hohenstine photographed each of the 2,000-plus displays and turned them into slides that he used to educate fellow jewelers and gemologists. He gifted dozens of the slides to former employee and longtime family friend Judith Allen Hall when she began teaching. Hall donated the slides to GIA’s Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center in 2016.

Here, she remembers the remarkable process Hohenstine followed to create fresh window art for his store for decades.

Mr. Hohenstine made a dozen opaque glass plates with matte surfaces and gilded wood frames. Each was about 10-12 inches in diameter. Some were round, others square; some were white, others were pale green. A couple of them had a small hole drilled in the plate. Under the plate was some sort of a small motor, and on top of the plate was a post that held the 10-ct. diamond upright so that it rotated and glittered.

He would begin by drawing the design on the plate with a soft pencil, and then open the desk drawer full of loose gemstones. With tweezers and an optivisor, he would painstakingly start putting the gems in place. The tables of brilliant cuts would be turned in certain directions to give the illusion of depth. All of the gems were simply laid on the plate – there was nothing to secure them.

It took six or more hours to complete the design, depending on its complexity. Customers could look in the curved window in front of the diamond room window to watch him work.

He was very inventive and created a way to photograph every design. A camera was mounted facing downward in a cabinet behind his desk in the diamond room, and it was exactly the right height to put the completed gem design in focus. All you had to do was slide the glass plate on the shelf, push the camera button, and it was done. Each slide contained the number of the design and the number and type of gems included in the design.

Once the design was completed and photographed, it was ready for Tuesday night window trim after the store closed. The left front window was about 90 to 100 feet from the diamond room, which seemed like a mile if you were carrying the plate – which was ever-so-slightly tilted, with the unsecured gems in place.

The left window had one-inch thick, bulletproof glass and a huge I-beam under it, so that street and foot traffic would not jar the design. The back glass lifted up when unlocked to give access to the window. The old design was very, very carefully removed and put on the showcase behind the window. Care was taken so that if there was any calamity getting the new one in place, the old one could be put back in the window.

When the new design was in place, Mr. Hohenstine would put on his optivisor and pick up tweezers and move any gem that might have been displaced. Then the frame was put in place, along with a little typed sign that would read something like: “This is the 1543rd design and contains 200 rubies and 56 emeralds.”

The old design was then carefully carried back to the diamond room, and the next day he would take it apart and put all the little gems back in their respective envelopes.

Judith Allen Hall is a retired gemology instructor with more than 30 years of university-level teaching experience in South Florida. She was a family friend and former employee of M.D. Hohenstine.