Gemstone ‘Paintings’ Tell Story of a Master Craftsman, Gem and Jewelry Mentor

April 27, 2018

“For the first Christmas in 50 years, there is no intricate, shimmering picture woven of hundreds of gemstones to decorate the holiday display window of the jewelry store at 37 S. High Street on the ground floor of the Neil House. A tradition that gave a unique flavor to Capitol Square and warmed the hearts of generations of Columbus visitors and shoppers since 1927 has ended with the death of the artisan who painstakingly handcrafted gem paintings for all seasons.” – Columbus Citizen-Journal, 1976 obituary of M.D. Hohenstine

Aside from a few mementos available for sale on Etsy and eBay – a vintage rose gold brooch, a sterling silver spoon, a taxidermy butterfly serving tray – along with a handful of business directory listings and an obituary in the local newspaper, there isn’t much of an online record that tells the story of jeweler M.D. Hohenstine and his Columbus, Ohio retail store.

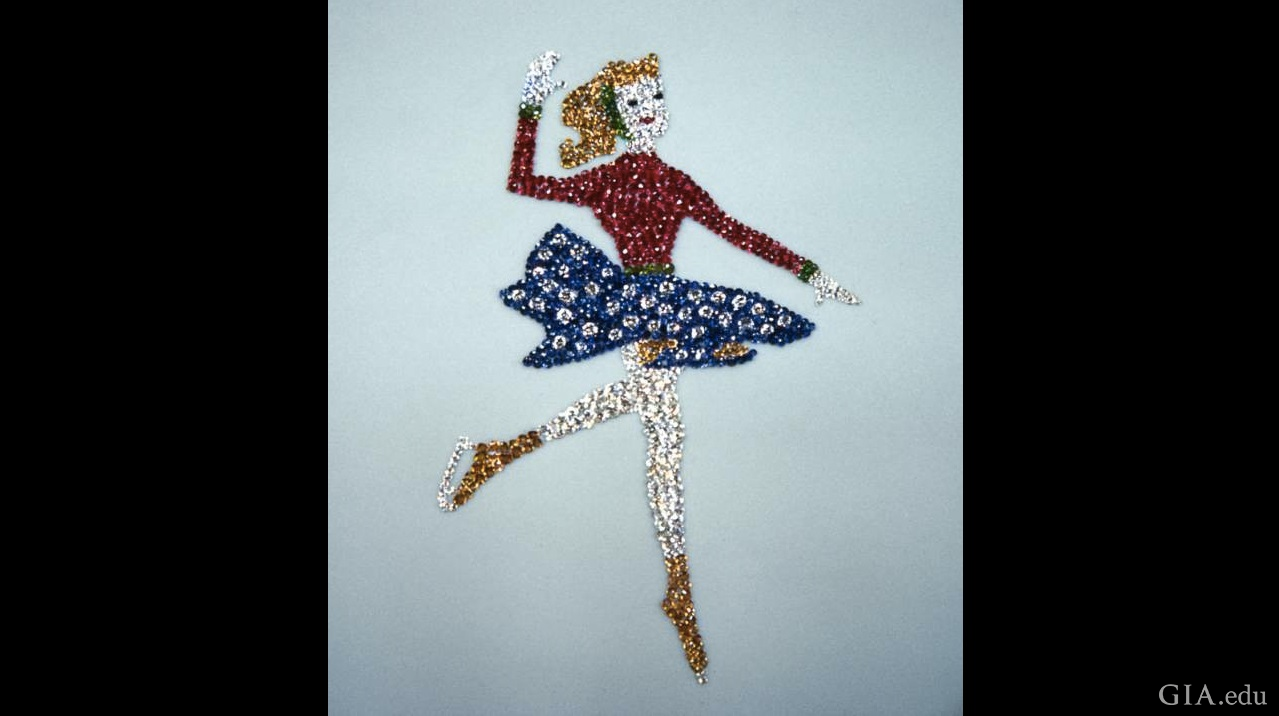

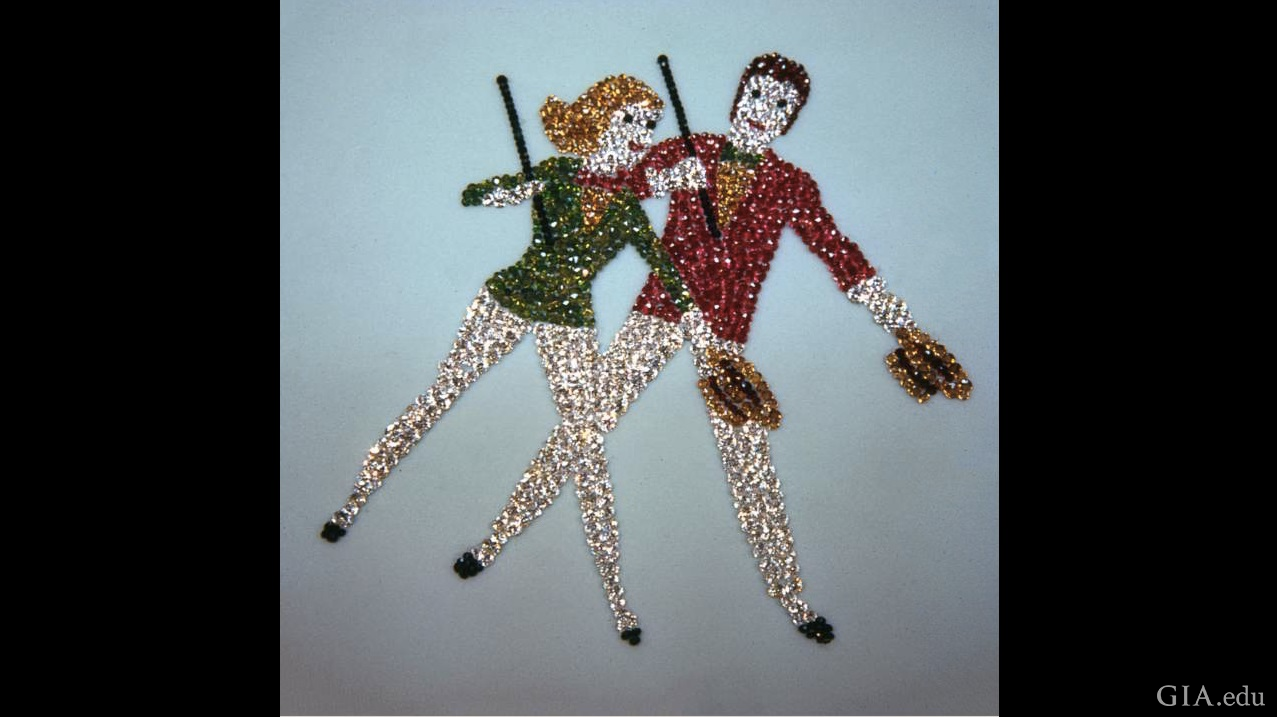

And yet, Hohenstine’s spectacular window displays, featuring elaborate, artistic arrangements of hundreds of loose gemstones, were a creative and logistical marvel that captured the imagination of Ohio’s capital city for decades.

“People traveled to Columbus from all over and made a point of going to see ‘the window,’” remembers former employee and longtime family friend Judith Allen Hall. “During the Christmas season, people would sometimes line up three and four deep, trying to look in. Over the years, so many feet stood in front of Hohenstine’s store window that the pavement in front of it had to be repaired because of depressions in the concrete.”

M.D. Hohenstine Jewelers sat in the heart of one of the city’s most bustling neighborhoods, where visitors toured, entertainers performed, and politicians and military personnel were welcomed with parades and fanfare. Its location in the historic Neil House hotel – across from the state capitol building, down the street from the iconic Lazarus department store and the city’s theater district – along with its dramatic curved windows and rich, oversized mahogany display cases, drew actors, big-band and jazz musicians, and entertainers, including the apex of jewelry-loving celebrities, Elizabeth Taylor.

“I’m sure whatever design was in the window was what drew her in that day,” says Hall, who notes that “Mr. H,” as employees called him, stayed in the back of the store and let staff have face time with the A-lister as she browsed the counters.

Family members, like Hohenstine’s grandchildren, still look back fondly on their visits to 37 S. High Street. “My favorite memories always included seeing his gemstone displays in the store window,” says Hohenstine’s granddaughter, Tracy Hagen-Smith.

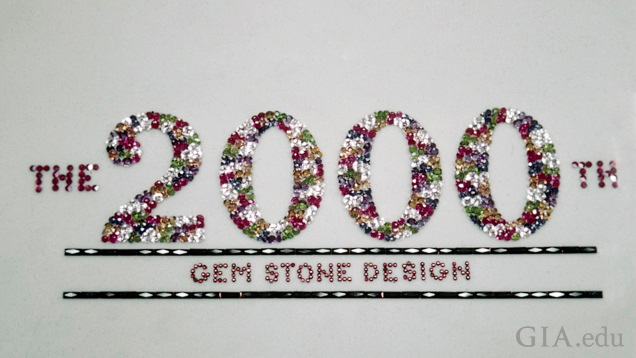

As much as Hohenstine’s intricate displays – all 2,000-plus of them, catalogued diligently in 35-mm slide photographs – drew public attention, he also quietly built a circle of inspiration and influence within the gem and jewelry industry. Hohenstine’s behind-the-scenes mentorship and willingness to pass on his extensive knowledge of gemology, bench jewelry and the logistics of business operations, has continued through generations of GIA-educated jewelers and gemologists long after the doors of his business closed.

‘Tuesdays Were Display Days’

Gems & Gemology featured Hohenstine’s 1,039th design on its cover in 1951, and noted his “effective window displays,” which started with his collection of hundreds of loose, natural gemstones.

“None were synthetic,” Halls says, “and none were for sale.”

Hohenstine kept the gems he used for his displays in the left drawer of his custom-designed desk, wrapped in papers scrawled with notes like “56 rubies” or “one 10-ct diamond.” He used a soft pencil to sketch designs, often celebrating a season, holiday, local sports team or charity organization, and meticulously arranged the gems over them. Each slide was marked with a number in one corner, and the gems’ identification in the other. The process took at least six hours, and customers walking by could look into Hohenstine’s secure diamond room and watch the craftsman at work.

The gemstone arrangements – unsecured in any way to the plates – were then photographed and carefully carried 100 feet from the diamond room to the window for dressing.

“Tuesdays were display days,” says Hall, who remembers many of the details of how Hohenstine created his window displays. “Every other Tuesday evening, from 1927 until his death in 1976, he trimmed the windows, and a new gem design went in the center of the left window facing the capitol – even on the Hohenstines’ 50th wedding anniversary!”

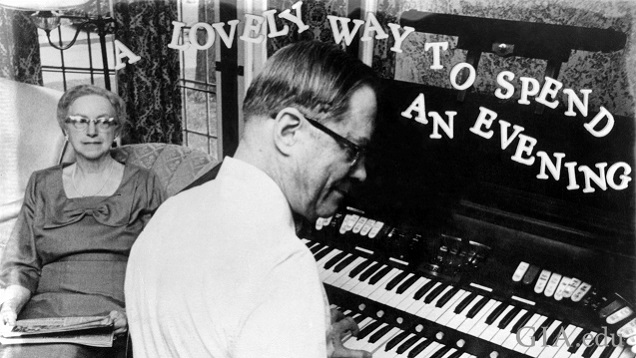

The slide photographs weren’t simply for posterity. Hohenstine used them as an educational tool for his frequent lectures to gem and mineral societies, as well as civic organizations, such as the Kiwanis Club, for several decades.

A Mentor in Jewelry, and Advocate for GIA Education

Hohenstine was born in 1891 and grew up in a relatively poor family in Columbus’ German Village neighborhood; after finishing eighth grade, he helped earn money for the family by working for well-known jeweler and watchmaker Edwin S. Albaugh. Hohenstine married Albaugh’s niece, Margaret Vause, and eventually opened his own small jewelry store in downtown Columbus. Business became so robust that he moved his store to the larger Neil House location in 1927, where it continued to thrive in a competitive area.

He helped differentiate himself early on. “When he learned about GIA courses, which were by mail at the time, he promptly signed up and became an early Certified Gemologist [today’s GIA GG],” Hall says. “He was so proud of that.”

Hohenstine hired Hall’s father, Lawrence Allen, who had also apprenticed under Albaugh and well-known local jeweler, Curly Miller, in 1935. Hohenstine became a friend and mentor to Allen over the next five years, as Allen also began to earn his Certified Gemologist diploma from GIA. Allen left to open his own store, Allen Jewelers, in nearby Mount Vernon, and become vice president of the Ohio Jewelers Association, but the two stayed in touch.

Hall visited Hohenstine’s store with her father as a toddler, and at 12 years old, began to work alongside him at Allen Jewelers in 1948. “I sat next to him every day at the bench,” says Hall, until she started high school.

Tragedy struck the Allen family shortly after Hall’s graduation in 1954, when her father passed away unexpectedly at 41. Hall, only 19 years old, took the reins of the family store and managed it for a few years until their landlord sold the building and the family shuttered Allen Jewelers permanently.

Hall and her sisters – all trained in the trade – moved to Columbus and joined different jewelry stores. Her father’s old friend M.D. Hohenstine welcomed Hall to his business with open arms. He proudly displayed her Registered Jeweler certificate from the American Gem Society, which she had earned while running the family store, on the wall of M.D. Hohenstine Jewelers – right alongside his own. This was notable, Hall says, as women’s roles as professionals in the gem and jewelry industry were not yet fully accepted in some circles.

She worked alongside Hohenstine for eight years, handling sales, assisting in his window display dressings, and eventually with his encouragement, dipping into the world of gem education. Hall lectured and gave presentations on behalf of M.D. Hohenstine Jewelers until the store was bought in 1966 by fellow jeweler Thomas Hawk. Hohenstine continued to work there, still creating his biweekly gem displays, as Hall moved on to Florida, to teach gemology at multiple schools, including the University of South Florida in Tampa.

A Legacy of Sharing Knowledge

Hall, who took gemology and design classes at GIA through the years, launched into teaching and reached out to her mentor in 1974 with a letter requesting copies of the window design slides.

“At first I asked him because I was trying to fill up 30 hours of class time,” she laughs.

Hohenstine wrote back that he would not send her copies, but originals – though he had previously refused every other request for them from others.

“I am sending 40 slides from my collection as a gift,” he wrote, “with the understanding they are to be used for educational purposes.”

From that point on, Hall never taught a class without them.

“People were always excited to see them,” she says, “and fascinated that someone would have that big of a collection that was not for sale.”

Over the next few decades, Hall encouraged her students – many working jewelers and pawnbrokers – to continue their studies at GIA. In a profession like pawn brokerage, she explains, professionals have to make decisions quickly, with nothing more than a loupe in hand and gemological knowledge in their heads.

“I convinced many of them to take GIA classes,” Hall says. “I explained that having that foundation of GIA knowledge is what allowed me to identify gemstones quickly in the first place.”

One of those students, Shane Socash, was a working jeweler looking to expand his gemological knowledge.

“Judith exposed me to the history, lore and beauty of gemstones that I wasn’t getting in other parts of my jewelry education,” says Socash, who went on to earn his Graduate Gemologist diploma and become the owner of David Reynolds Jewelry & Coin in St. Petersburg, Florida. “It allowed me to broaden my knowledge, and I knew since she studied at GIA, that I wanted to explore that direction in my life, too.”

When Hall retired from teaching in 2016 at 80 years old, she began to think about the best home for Hohenstine’s slides, including those sent to her by Hawk upon Hohenstine’s passing, and the first edition of Richard T. Liddicoat’s “Gem Identification” book that he gave her.

“In the process of deciding where the best permanent home for them would be, I concluded that GIA is the connecting thread that links us together,” she says. “It’s the vehicle through which and by which we not only receive education, but we also can use to pass on our passion and knowledge of gems and jewelry industry history.”

Hall inquired whether GIA’s Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center would be interested in a donation to further gemological education. She was “thrilled” when librarians said they would be honored to safeguard the slide collection that Hohenstine had entrusted to her so many years ago.

“For me, that connecting thread was that Mr. Hohenstine, who was an early GIA graduate, taught my father, who also became a GIA graduate,” she says. “My father inspired me to study at GIA, and as a recipient of two generations of jewelry industry education and knowledge, I taught for 30 years and was able to inspire graduates like Shane Socash, who passes on his knowledge to his clients, and even his daughters.”

It’s been just shy of a century since M.D. Hohenstine installed the first of his “handcrafted gem paintings,” and 40 years since he created his last. But because he invested in the next generation of the gem and jewelry industry, his legacy of knowledge, craftsmanship and creative excellence will continue to inspire jewelers in the years ahead – far beyond the borders of the town where he created such unique and memorable art.

Jaime Kautsky, a contributing writer, is a GIA Diamonds Graduate and GIA Accredited Jewelry Professional and was an associate editor of The Loupe magazine.