Gem Guide Delivers Education, Social Return to Artisanal Miners

January 21, 2019

Free educational tools provided to miners in some rural areas of Tanzania are helping them reap greater profits.

“[The miners] can sort, they know how to wash and add value into the material … They are really now getting more money than when they didn’t have this project. It has added a lot of value into their life using a book and using a tray,” said Salma Kundi Ernest, secretary general of the Tanzanian Women’s Mining Association (TAWOMA), speaking through an interpreter at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference, held in October 2018.

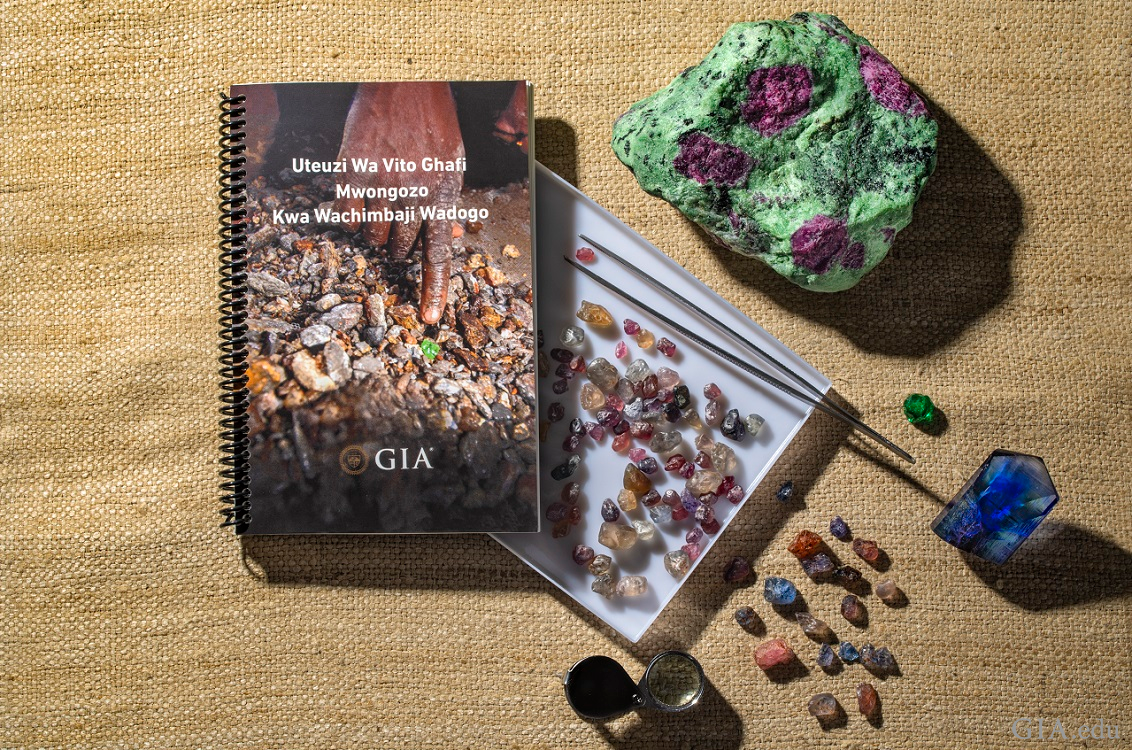

The artisanal miners gleaned this valuable knowledge from “Selecting Gem Rough: A Guide for Artisanal Miners,” an illustrated book developed by GIA (Gemological Institute of America) to help small-scale miners learn more about the quality and classification of the gems they recover.

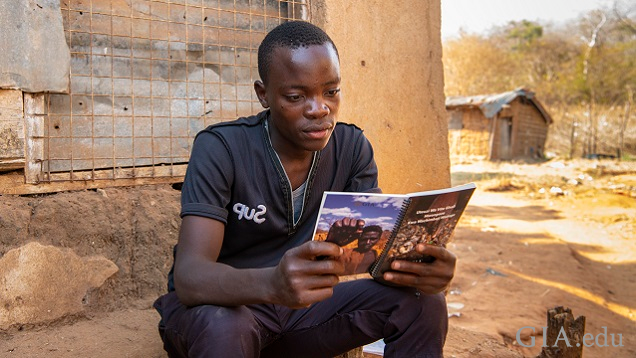

Artisanal small-scale (ASM) miners, working in small teams using only hand tools, mine many of the colored gemstones from Tanzania and other areas around the world. They often live and work in remote areas where there are few other opportunities to earn a living and have little or no access to information about the stones they recover. Having even simple information about gem quality and an understanding of market needs puts them in a stronger position to negotiate with buyers.

The “GIA Guide for Artisanal Miners” is a photo-rich booklet written in Swahili with photos of the rough gemstones found in East Africa, including tourmaline, corundum, various types of garnet, topaz, spinel, zircon and tanzanite. Since most of the miners have little formal education, the information is presented primarily in pictures, with limited text. Accompanying the water-proof booklet is a durable plastic translucent tray that can be used to sort gems and do other basic gemological evaluations. The pictorial instructions guide the miners – including those who cannot read – on how to evaluate the quality of the rough.

Other illustrations show how to use the tray to view the rough gem material using both direct and transmitted light to best evaluate the gem’s characteristics and how to clean it. A section at the end shows the stages of gemstone cutting from sawing to pre-forming and faceting, and then how a stone is mounted into jewelry. This information gives the miners a better understanding of the market value chain.

GIA contracted with Pact, a Washington, D.C.-based non-governmental development organization with offices in Tanzania and extensive expertise and experience in the region, to conduct two pilot studies – one in 2017 and one in 2018. The first pilot trained approximately 400 artisanal small-scale miners in the Tanga region near the northern border of Tanzania, which GIA and Pact selected because of the diversity of alluvial gemstone deposits in this area. The initial participants were members of TAWOMA.

“We were keen to involve TAWOMA because female miners have faced even more challenges than their male counterparts: sex discrimination, exclusion from some mining sites, less mining knowledge, less access to capital and less education in general,” said Cristina Villegas, director of the Mines to Market program at Pact. “When it comes to education, why not start with women?”

The second pilot distribution reached approximately 750 additional miners in the gem-rich regions of Tunduru, Songea (in southern Tanzania) and Morogoro (in central Tanzania). The Tanzanian government was informed about each of GIA and Pact’s visits and endorsed their efforts. Norbert Massay from Pact provided travel logistics, government contacts and information about mining localities.

GIA staff, including Robert Weldon, director of the Richard T. Liddicoat Gemological Library and Information Center at GIA and co-author of the guide, and GIA Graduate Gemologist (GG) Marvin Wambua from Kenya, trained artisanal miners in how to use the guide and translucent tray. All of the miners, who were surveyed several months after being trained, said they developed a solid understanding of the gemological concepts presented. The survey results also revealed that they gained confidence in evaluating the quality of rough they found, which dramatically improved their bargaining power with local buyers.

Wambua, who is also a gem cutter, noted the higher quality of the rough offered from the mining groups. “Prior to the program,” he said, “we didn’t see anything worth cutting. But as we progressed, quality in the samples improved. On our follow-up visit in Tanga, I saw gems worth working on.”

One miner noted that learning how to wash gemstone rough properly made it possible to evaluate the quality of the color and clarity of her finds. Another said that this ability enabled him to separate gems by type and quality, which got him much higher prices in the market.

“I have sold my garnet for 70,000 Tanzanian shillings (about $30 US) after the training. Before I would have received a maximum of 10,000 shillings,” a female miner from Kalalani (near Tanga) told Pact.

Pact calculated that the the knowledge gained from GIA’s $120,000 initial investment in the project – funded by the GIA Endowment fund – generated a 12-fold social return on investment (SROI) to the miners and would continue to help them in coming years.

Massay reported that benefits from the gem guide extend far beyond the miners themselves. “I can see how this is changing things here. People have more money, more kids are in school, more of them have school uniforms and people are building brick houses. All of this shows that it is bringing more value into peoples’ lives,” he said.

The idea for the gem guide project started with Dr. James Shigley, GIA Distinguished Research Fellow, following a 2008 trip to Kenya and Tanzania. Seeing the artisanal miners working under difficult conditions, he started thinking about the best way to help them. He, together with GIA library staff, developed the text and photos for the guide, with extensive consultation with other experts in the gem trade. First developed in English, the booklet was later translated by Wambua into Swahili.

GIA assumed all of the costs for the pilot project from its endowment fund and will continue to provide the book, tray and training free of charge as the program expands in East Africa and other potential gem localities.

“This is core to the GIA’s mission,” said GIA President and CEO, Susan Jacques. “We are moving practical gemological knowledge to the beginning of the supply chain for the people who can benefit from it tremendously,” she said. “This guidebook brings artisanal miners understanding about the value of the beautiful gems they bring to market.”

Weldon, who was involved with many of the phases of the project, was pleased to see the positive impact the gem guide had on the artisanal miners’ lives and work.

“An understanding of the very basic needs of African miners at the beginning of the supply chain was absolutely key for this to work,” he said. “It is truly humbling to see that the knowledge gained by the miners is helping so much. As they begin to understand the complexity of the supply chain, and how gems are used, these miners can aspire to different jobs, such as cutting and jewelry making.”

Russell Shor is a senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.