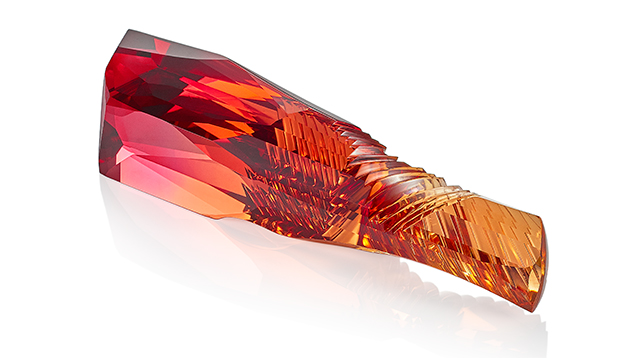

Cutting the ‘Imperial Flame’ Topaz

April 28, 2016

One of the most spectacular gems at the 2016 Tucson show was a magnificent freeform 332.24 ct Brazilian topaz on display at the GJX booth of gem artist Alexander Kreis (Sonja Kreis Unique Jewelry, NiederwoErresbach, Germany), which the Kreis family has named the “Imperial Flame.” Described by International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA) executive director Gary Roskin as a “showstopper,” this spectacular gem was cut from an exceptionally rare 615 ct crystal.

Alexander Kreis specializes in unique cutting styles. He comes from a 500-year family tradition of gemstone cutting and jewelry making. The business is still a Kreis family affair: Alexander’s mother, Sonja, and sister, Vanessa, design the jewelry pieces that best complement his gems’ style, and his father, Stefan, procures the rough. Gems have been part of his life from an early age, as his father traveled the world dealing with rough stones. The young Alexander was fascinated by stories of faraway mines and the little bags of rough crystals his father brought back. This spurred him to pursue a traditional apprenticeship, where he learned the fundamentals of gem cutting. However, Alexander broke from tradition to follow his own unique appreciation for beauty. He strives to use the rough in a nontraditional way.

Kreis always seeks the beauty in rough material. “Nowadays to find the right rough material is really challenging,” he notes. “Demand is growing for better material, especially in Asia.”

Which brings us to the spectacular topaz: According to the family, the crystal came from Brazil’s well-documented Ouro Preto topaz mines. Topaz has been recovered from this area of Minas Gerais for over 200 years, with the first discoveries recorded in 1768, when the Portuguese court of King Joseph I marked the discovery of the gem in their Brazilian colony with a “splendid celebration” (P.C. Keller, “The Capão topaz Deposit, Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, Brazil,” Spring 1983 Gems & Gemology, pp. 12–20).

Today, as in the 1700s, topaz with this red, pink, or orangy yellow color component is rare and very valuable. One of the most sought-after colors is known as “Imperial” topaz, which most in the trade consider a medium reddish orange to orange-red. As noted in previous reports, only one to two percent of all the material recovered from Ouro Preto’s mines is of faceting quality, which makes the caliber of this crystal all the more remarkable. (see D.A. Sauer et al., “An update on Imperial topaz from the Capão mine, Minas Gerais, Brazil,” Winter 1996 Gems & Gemology, pp. 232–241).

Although these topaz mines were once very active, there is no longer mining of any scale. To the best of the family’s knowledge, the crystal is “old production” mined at least 20 years ago. They first learned of it in September 2015 from an old acquaintance, an avid collector who believed Alexander could create something exceptional from the crystal.

In September 2015, Stefan and Alexander Kreis traveled to Brazil to view the stone. When they saw the crystal, they immediately recognized it as something “truly exceptional” that might be fashioned into a “piece of the century.” As family member Carsten Kreis remarked, “It has the rare red color as the main part. But what makes it even more beautiful for us, is that it depicts the whole range of warm colors an Imperial topaz can have, and does so with an amazing intensity.”

Sonja Kreis Unique Jewelry.

The Kreis family acquired the topaz in December 2015. Before making a commitment to buy, they spent most of the previous four months analyzing the crystal to determine a fashioning plan. Although they briefly considered cutting the piece as three or more separate gems, their objective quickly became to cut the largest known top-quality Imperial topaz.

From the outset, Alexander realized that the sheer size and clarity of the rough was astounding and that this combination, along with the range and intensity of colors, was “just unbelievable.” After much contemplation, Alexander finally decided to fashion the crystal into a single piece. This decision, he recalled, came “out of love for the mineral…as a sculpture it would be something that hasn’t been done before.”

As a gem, topaz has an Achilles heel—its basal cleavage. As a result, cutters must exercise extreme care to avoid grinding the stone perpendicular to the cleavage plane. Inclusions might also cause the stone to break on the wheel. According to Sauer et al. (1996), weight recovery depends on the amount of inclusions in each crystal. Well-formed, fairly clean crystals yield up to 2 ct per gram (5 ct), or a recovery rate of 40 percent.

Because of this inherent physical property, topaz—especially in larger sizes—is challenging to cut, giving every savvy cutter pause for thought. “Imperial topaz is very difficult to cut because the gem has a tension residing in it,” says Alexander. “Thus, we had a thorough look at it—especially for inclusions that could release that inner tension and lead to the crystal breaking.”

Alexander started the cutting process with the intent of retaining as much weight from the crystal as possible while striving for the highest level of artistry. “You want to waste as little material as possible and at the same time bring out the most of its potential beauty,” he explained.

Fashioning the crystal took a total of eight days, spread across a period of three to four weeks. Alexander stopped the cutting process from time to time to make test carvings with smaller pieces of Imperial topaz in order to gauge the reaction of his cutting concepts on the Imperial Flame. There were three stages: sawing or trimming away any fractured or included material, grinding to preform and shape the solid crystal, and faceting along with carving the reflective, grooved surfaces. The exact cutting procedure, equipment, and polishing compounds Alexander uses are proprietary. Previous sources (e.g., Sauer et al., 1996) indicate that Brazilian topaz cutters use a 360 grit grinding wheel and a 600 grit faceting disk, polishing the stones on a lead/tin lap with Linde A (Al2O3) powder. From an original weight of 615 ct, the cutting process yielded a finished gem measuring 89.53 × 20.56 × 19.15 mm and weighing 332.24 ct, a finished yield of 54 percent.

Regardless of the exact methods used, the finished piece is a spectacular crystal sculpture: a winning blend of geometric flat facets and curves bearing carved grooves that reflect and reinforce the red to rosy peach hues of the topaz many times over. The carving produces glittering reflections that enliven the lower portion of the sculpture and lead the eye to the blaze of red at the tip of the crystal. It is truly a special piece fit for a connoisseur or high-end collector.

“Is it for sale?” we asked.

“Yes,” came the answer. “Price upon request!”

Duncan Pay is editor-in-chief of Gems & Gemology.

The author would like to thank the Kreis family: Alexander, Stefan, Sonja, Vanessa, and Carsten for all their help answering questions about the imperial flame topaz and for the many photographs they provided for the article.