Bright Light at Midnight: Canada’s Far North Land of Diamonds

November 20, 2015

The diamonds remained hidden until 20 years ago because the unforgiving climate deterred all but the hardiest of human beings – the northern First Nations tribes who have lived there for thousands of years, fishing and trapping for sustenance – from exploring the area.

Arriving at Yellowknife, 62.4 degrees latitude, just before midnight in the June solstice, the sun is still well above the horizon. Photo by Russell Shor/GIA.

In the 10 weeks of summer at the 64th parallel there are literally endless days, with several weeks of 24-hour light. There is just enough time for the vegetation − dwarf birch, northern Labrador tea, blueberry, mountain cranberry and sphagnum moss − to survive as feed for the herds of caribou that migrate over the rocky terrain in the fall and spring.The first freeze returns with a vengeance in late September and brings with it the spectacular lights of the Aurora Borealis. The guidebooks say this part of the world is the best place to see nature’s show, and 50,000 tourists journey to the northernmost cities, Whitehorse and Yellowknife, each fall for a view. By December, the temperatures are down to -40°C (-40°F) and there’s but a glimmer of twilight at noontime.

Caribou are essential to the ecology of Canada’s northland. Photo courtesy of Rio Tinto

The few outsiders who ventured up to the area in the last century and a half were looking for treasure – gold at first, as with the Klondike gold rush of 1897–99. By the 1930s, gold prospectors moved farther east to the Northwest Territories and developed the provincial capital of Yellowknife. At 100 miles south of the tree line, the town sits on the north bank of the Great Slave Lake, near two gold mines. The Great Slave (named after the Slavey tribe that inhabits the area) is the world’s 10th largest lake, covering well over 10,000 square miles, and the deepest in North America, plunging more than 2,000 feet in some spots.The tree groves that surrounded Yellowknife provided a nearly unlimited source of building materials, first for log cabins, then for processed wood beams and siding. As Yellowknife grew into the provincial capital, prospectors rarely ventured much farther north beyond the tree line, the gold mines wound down, and money stopped pouring into the town.

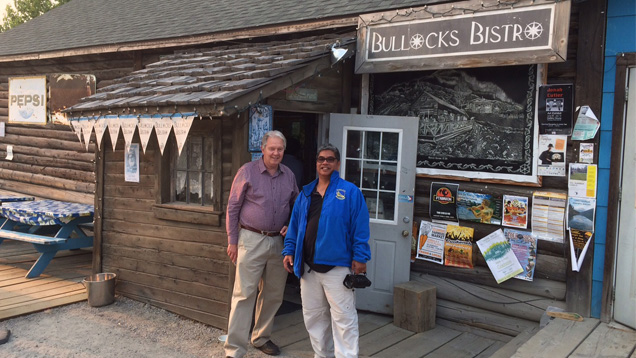

Dr. James Shigley, GIA Distinguished Research Fellow, and Pedro Padua, a videographer for GIA, stand in front of one of Yellowknife’s first structures dating from 1935 when most of the settlement was built from logs. Photo by Russell Shor/GIA

A half-century later, another type of prospector came to the region – geologists searching for diamonds.They were there for sure. People had been finding diamonds in rivers and creeks as far south as Montana in the U.S. for decades. De Beers wanted to find them first, dispatching exploration teams north in the 1980s toward the Mackenzie Mountains near the Yukon border. The team did discover garnets, chromites and ilmenites, minerals that told them diamonds could be nearby, but no diamond sources.

Yellowknife, the closest city at that time, was facing an economic decline, so when De Beers chose it as the staging area for exploration, the locals welcomed it. When the word went round that the De Beers was on the scene, others paid attention, including Superior Oil, a California-based company exploring the area for other minerals.

Charles Fipke, left, and Stewart Blusson traversed the rugged and remote terrain of Canada’s Northwest Territories for years in their quest to find diamonds. Left photo by GIA; right photo courtesy of Stewart Blusson.

Superior Oil dispatched geologist Charles Fipke in the early 1980s and a team that included another geologist, Stewart Blusson, to the Mackenzies to explore for diamonds. They found the same indicator minerals as De Beers, but Standard Oil quickly lost interest in the project.The two geologists knew they were on the trail, but it was Blusson, with his strong knowledge of the region’s glacial history, who understood that the glaciers were the key. They carried the indicator minerals across the expanse of barren land that also happened to host the oldest known rocks on Earth (more than 3.9 billion years), making this prime diamond country. The geologists kept up the search, using their own funds to follow the pyrope garnet trail eastward.

Blusson rented and piloted a helicopter to plot a course, setting Fipke on the ground to collect samples until the fall temperatures fell well into the minus range and daylight nearly disappeared. After three years, the composition of samples strongly suggested diamonds, but the money was running out, so Fipke embarked on a fundraising plan to sell shares in an exploration company he founded, DiaMet Minerals.

Lichen covered rocks and sparse vegetation cover most of Canada’s far north where the growing season is only a few weeks. This is the type of terrain Fipke and Blusson traversed for years as they followed the trail of pyrope garnet. Photo by Russell Shor/GIA

Eight years into the search, the indicator minerals around one large lake were off the charts, but the money was again running out and the encroaching winter had made it impossible to continue. Fipke returned in April 1990, with the ground still frozen solid and enough money for one more day of digging. On that day, after hard digging, he and his team found more indicators, including a large chrome diopside, which told them they were practically standing on a kimberlite pipe.With these samples, Fipke was able to convince the mining giant BHP to front the funds to finish the job in exchange for a 51% share. Eighteen months later, while war raged in Kuwait, the company announced it had found a world-class diamond deposit at the bottom of Lac de Gras.

Diavik Mine

Discover the expansive, beautiful and harsh environment of Canada’s Northwest Territories and go behind-the-scenes of a Canadian diamond mine.

Developing the deposit, which became the Ekati Mine, tested the ability of BHP to develop a large mine without compromising one of the world’s last pristine wildernesses. The lakes are as pure as when they were formed. Despite its barrenness, the area is home to five First Nation tribes (two branches of the Dene First Nation, the Tlicho peoples, the Kitikmewot Inuit and the North Slave Metis), all of whom follow the caribou herds for sustenance, maintaining an ecological balance that has endured for millennia. Mine construction had to ensure the caribou would continue to migrate, which meant preserving all vegetation and ensuring their safe passage through the mining areas.Today, Canada is the world’s fourth-largest diamond-producing nation. Ekati opened in 1998, followed by Diavik five years later and Snap Lake another five years after that − all within 50 miles of each other. A fourth, Gahcho Kue, will open next year. These, plus the Victor mine in northern Ontario, yielded over 12 million carats in 2014, valued at just over $2 billion.

Exploration teams continue to traverse the northern wilderness. Two mines are under construction elsewhere in Canada, at Fort à la Corne in Saskatchewan and Renard in Quebec, and there are other sites under evaluation.

The long Arctic winters bring seven to eight months of white landscapes and frozen lakes. The Diavik Diamond Mine, above, is in a kimberlite cluster around frozen Lac de Gras. Photo courtesy Rio Tinto

For all of the difficulties the extreme winter brings, it also presents opportunity. There are no roads beyond Yellowknife, which lies about 200 miles south of the kimberlites. In the deepest of winter, the lakes freeze hard enough to construct an ice highway that heavy trucks use to resupply the mines for the entire year – the difficulties and dangers the ice road truckers face have been well-documented.The dangers of just being out in this unforgiving winter climate are well known, and the diamond mines have strict rules about employees venturing out in winter. No one can leave their work area without a buddy or go outside during a whiteout blizzard, because people can quickly become disoriented and die from exposure only a few yards away from safety.

“It can happen like that,” said one supervisor at Diavik, snapping his fingers.

About the Author

Russell Shor is GIA’s senior industry analyst. He attended the opening of the Ekati Diamond Mine in 1998 and recently visited the Diavik Mine.