Revealing “The Angel in the Stone”: The Largest Known Square Cushion-Cut Tsavorite

More than 50 years after Campbell Bridges discovered the green grossularite garnet later named tsavorite, the company that bears his name carries on his legacy of ethical sourcing and mine-to-market transparency. At the 2019 AGTA Tucson gem show, Bridges Tsavorite unveiled the largest known square cushion-cut tsavorite, weighing 116.76 ct. In March 2018, a GIA team traveled to Bridges Tsavorite’s Tucson office for a look at world-renowned gem cutter Victor Tuzlukov’s approach to cutting this rare gem.

The 283.74 ct rough stone (figure 1) was mined by Bridges Tsavorite in Merelani, Tanzania, in September 2017. Bruce Bridges, the company’s CEO and son of the late Campbell Bridges, told us that the rough was extremely clean for its size. It had several very well-terminated euhedral faces, unusual for tsavorite, which typically has more fragmented face formation.

The company had already received many inquiries from around the world about purchasing the stone post-cutting. Bridges said the buyer would likely be a knowledgeable collector or a jewelry connoisseur; retail jewelers rarely purchase stones of this value except on request from a high-end client.

Bridges Tsavorite sorts and cuts all of its production in-house. Bridges said they have always prided themselves on having a transparent mine-to-market supply chain. “The public nowadays really wants to know more about a gemstone: Where did it come from? How did it get from raw to cut?” he said. “I’m really happy about documenting the entire process, from rough to finished product.”

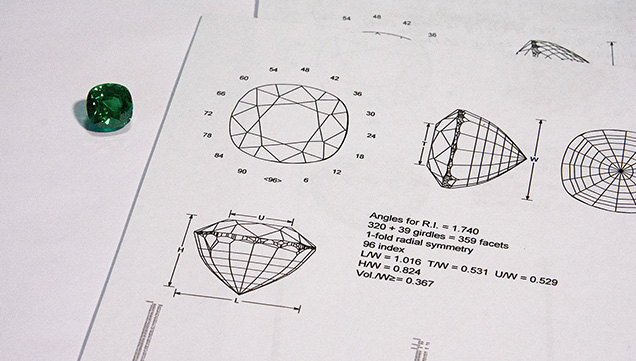

Along with the rough stone, Bridges showed us two cut tsavorites (figure 2): a 31.57 ct square cushion cut and a 58.52 cushion cut. Tuzlukov had just finished cutting the 31.57 ct tsavorite (figures 3 and 4). Planning the cutting process took six weeks; he then spent five days cutting the stone, working from 9 to 11 hours each day. Bridges said that along with the rough, these were the three finest tsavorites he had ever seen in their respective sizes. For Tuzlukov, cutting the 31.57 ct stone was a timely preparation for cutting the larger square cushion cut.

“Somebody said ‘I saw an angel in the stone and cut until I let him be free,’” Tuzlukov said. “I also try to see something inside the stone.”

Bridges and Tuzlukov began discussing the approach to cutting the 283.74 ct rough in early February 2018. Tuzlukov showed us on the rough tsavorite where he envisioned the table, the crown, and the pavilion. He said sometimes he knows immediately upon looking at a rough stone what the cut stone will look like (figure 5). Other times he thinks about it “for months or longer.” His approach to cutting gemstones is undeniably metaphysical. “I try to join my consciousness with the stone,” he said. “I try to explain to him that we go to perfection together. Sometimes when I get full contact with the stone, the stone begins to help me. Not by words—just by feeling. I feel when I have to stop when cutting.”

Originally from Russia, Tuzlukov lives in Bangkok, where he facets top-quality gemstones, creates original designs, and teaches faceting at the Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand. He worked as a marine navigator and an economist before being introduced to gemstone cutting by a friend of a friend. He obtained his G.G. from GIA in Moscow and began faceting gemstones in 1998. In 2006 he participated in the United States Faceters Guild Competition for the first time, and in 2010 he won the International Individual Faceting Championship in Australia (with a world record of 299.17 out of 300 points). Later that year he founded the Russian Faceters Guild and the faceting competition the Russian Open.

Tuzlukov said he tells his students “in the worst case you should be just two, you and the stone. In the best case, you should be one.” Sometimes he starts cutting, and then stops and comes back after some time—perhaps weeks—because he has not achieved what he calls “full contact” with the stone.

Tuzlukov used the 3D model of the rough tsavorite to cut a test stone from yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG), a synthetic material. Angles and indices were calculated following the shape of the rough to save as much weight as possible, and were adjusted to account for YAG’s refractive index, which is higher than tsavorite’s. After the YAG stone was cut, the real work began.

Tuzlukov began to cut the tsavorite during our visit (figure 6). The remainder of the cutting was accomplished over the course of about a month.

“The material is amazing,” Tuzlukov said. “It’s not only a pleasure but an honor for me to cut this.”

At the AGTA show, Bridges said the tsavorite (figure 7) could be a once-in-a-lifetime stone. Despite seeing most of the finest tsavorites in the world above 20 carats, he had never seen one comparable to this size in a square cushion cut. The square cushion and round cuts are the rarest shapes for tsavorite because the rough typically lends itself better to other shapes. Square cuts in particular result in the greatest loss of weight in cutting, he said. The tsavorite also has the distinction of being the largest tsavorite, and the largest gemstone of any kind, cut in the United States.