Geo-Literary Society Explores Diamond Cut

February 26, 2014

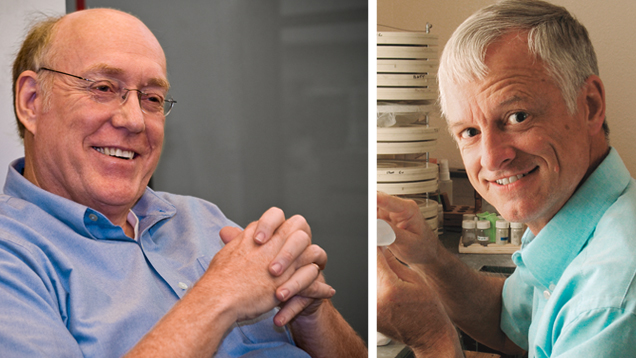

Sucher, president of The Stonecutter in Albuquerque, New Mexico, has created replicas of famous diamonds for more than 30 years. Gilbertson, a research associate at GIA in Carlsbad, California, has authored numerous articles on diamond cut and grading, as well as the 2007 book American Cut: The First 100 Years.

Sucher opened the session by chronicling the early history of diamond use, global trade patterns, and advances in cutting techniques and styles (see table). Using computer models, he compared the brilliance and fire of several early diamond cuts.

| Table: Milestones in the early history of diamonds and diamond cutting | |

|---|---|

| ca. 1000 BC | First archeological evidence of diamond as a cutting tool |

| ca. 300 BC | Early Indian manuscript discusses the qualities of diamond |

| 50 AD | Pliny’s description of diamond use in engraving and jewelry |

| 1200s | Development of the point cut (an octahedral crystal with polished faces); arrival of Indian diamonds in Europe’s royal inventories |

| Early 1300s | Establishment of cutting centers in Antwerp, Venice, and Amsterdam |

| Mid 1300s | Development of the table cut, a point cut with its top portion cut off to create a table-like surface |

| Late 1300s | Development of the single cut, a table cut with additional facets on the corners |

| 1400s | Advent of the polishing wheel (scaife), and the discovery of cleaving as a faster way of shaping diamond |

| 1500s | Improvements to the scaife, allowing polishing speeds of 1000 rpm |

| 1600s | Development of the Mazarin, a double-cut brilliant |

| 1700s | Development of the Old Mine cut, and the cutting of the famous Wittelsbach (prior to 1664) and French Blue (1671–1673) diamonds |

The discovery of massive diamond deposits in South Africa in 1867 changed the course of the industry, making these treasures available to a mass market. By 1870, there were 10,000 cutters in Europe. These artisans followed the shape of the original crystal and kept as much of the original weight as possible.

But the emphasis on weight retention was beginning to unravel thanks to Henry Morse, who had set up a cutting shop in Boston around 1860. Morse, who once said, “Shopping for diamonds by the carat is like buying a racehorse by the pound,” emphasized the cut of a stone and the brilliance that resulted. He invented a gauge to measure crown and pavilion angles, and devised his own set of best proportions. He also helped develop mechanical bruting, which increased the production of round-cut diamonds.

With turn-of-the-century improvements such as the circular saw, which made it easy to cut two diamonds from a rough crystal, the stage was set for the modern round brilliant. In 1919, Belgian engineer Marcel Tolkowsky published a landmark book titled Diamond Design, in which he asserted that the best-cut stones feature a 53% table, 59% total depth, and a knife-edged girdle. With some modifications to Tolkowsky’s proportions—an extended lower half, a larger table, and a closed-up culet—the round brilliant as we know it was established by 1950.

As Gilbertson pointed out, the breakthroughs in diamond cut planning and evaluation were just beginning. The Firescope viewer, developed in 1986, allowed the user to see a “Hearts and Arrows” pattern in a diamond cut to these “ideal” proportions. The Sarin scanner, introduced six years later, offered rapid, accurate proportion measurement, which led to the various cut grading services available today. Among other recent advances are inclusion-mapping software and high-speed laser cutting.

Following the presentation, Sucher invited the audience to view his faceted replicas of Cullinans I and II, the Koh-i-Noor, the Hope, and several other historical diamonds.

“Scott Sucher transported us to the early days of diamond cutting as we learned the first sources and tools,” said Dona Dirlam, the Geo-Literary Society’s secretary and the host of the session. “We saw how cutting styles evolved with improvements in the tools and an increase in the diamond supply. With each development, we saw this fascinating transformation through visual models.

“Al Gilbertson told us the largely unknown story of Henry Morse and chronicled the birth of the modern round brilliant,” Dirlam added. “As Al and Scott pointed out, today’s computer-optimized diamond cutting seems light-years removed from the earliest techniques.”

About the Author

Stuart Overlin is the editor of Gems & Gemology in Carlsbad, California.