Behind the Scenes of a Gemological Field Expedition

May 1, 2014

“Never go on a serious field expedition with people you don’t know. Make sure your team is ready and that they have the right attitude,” said Vincent Pardieu, senior manager for field gemology at GIA.

Gemology in the field is not the same as in a lab, he says. There are long stretches of communal living with nearly constant interaction with your traveling companions and reliance on local people to point you in the right direction.

Contrast that with a lab job where you get to go home every night and communicate with colleagues on your own terms, and you see that the challenges of fieldwork go well beyond gemological expertise.

“There is no way I will ask my boss to hire a person to work with me in the Field Gemology department based on a resume and few interviews,” Pardieu said. “To know if I can go on a serious expedition with a person, we need to spend time together in the field. Then I will be able to judge his skills and his attitude.”

Each member of the team needs to know precisely what he is expected to do, including how to interact efficiently with the other members of the team, Pardieu said. “Furthermore, a field expedition is about the gems, the place they are mined from and the people who mine them. The people are the key, because without their support you will not get where you want to go or get what you want to get.”

That is the context from which Pardieu, who is based in Bangkok, and Andrew Lucas, manager of field gemology for GIA Education in Carlsbad, broached the idea of traveling on a field expedition together when they met for dinner at a global GIA research meeting in late 2012.

Both gemologists have traveled extensively for their work: Pardieu to collect reference samples from gem mining areas to be used in laboratory work and Lucas to collect the details of the mine to market story for GIA’s education courses. Although their approach to gemology in the field is different, they soon found out they could learn from each other.

“During that evening we decided to try to combine our enthusiasm and our experience to build an efficient team that will benefit the lab and education,” said Pardieu, who asked Lucas to join his basic training program.

“Where do we start?” Lucas asked.

“Well, we already did,” Pardieu said. “It all starts with a good discussion around lunch or dinner. That’s the first time you get a sense of whether or not you have good rapport with each other.”

Trial Runs in Chanthaburi and Vietnam

Pardieu suggested that Lucas travel to Bangkok for a weekend field expedition to Chanthaburi (Thailand) and Pailin (Cambodia) to visit ruby and sapphire mines so he could see first-hand how Pardieu and his team works in the field for the lab. Next would be a 10-day trip that included Vietnam.

“Vietnam is one of the most beautiful and challenging place I know,” Pardieu said. “The jungle-covered mountains of the Luc Yen district, where rubies and spinels are mined, is also home to a lively cutting and trading industry. But it is dangerous terrain. If you are not careful you might fall, be wounded or even die.”

Pardieu told Lucas to expect the unexpected and to physically prepare his 57-year-old body for the expedition.

“If you survive Vietnam, then we will be ready to travel on longer expeditions to places as challenging as Central Asia or Africa,” he said.

Field gemology has significant risks. Pardieu, right, had a serious fall in a very treacherous and slippery ruby mine in Vietnam and suffered a significant fractured arm. This photo right after the accident shows his remarkable good spirit as he laughs with Lucas and still discusses the logistics of the trip. Photo by Clara Jennifer Haggai

Lucas did well on the May 2013 trip. Ironically, it was Pardieu, the younger man who warned everyone else about the rugged terrain of the mountains, who had an accident. He broke his left arm after losing his balance on some slippery marble pinnacles at the end of a long day of walking.

But what could have been a disaster turned out to be an interesting field experience for each member of the group, who banded together to immobilize Pardieu’s arm and carry him to help.

Ready to Explore Mogok

Pardieu and Lucas met again in November 2013, just after Pardieu had completed a successful scouting expedition in Mogok, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), a legendary gem locale in an area known as Upper Burma. The region opened to foreign visitors in June 2013 after being closed for many years. Pardieu felt he had recovered well enough from his accident to go for some serious exploring there, including some underground adventures using ropes and wooden ladders.

Lucas has previously visited Myanmar several times, but had never been able to visit Mogok, and jumped at the opportunity to collect information about it for GIA Education. The time was right, the feeling between the two gemologists was good, so they decided to partner up for a field expedition to Mogok, Pardieu said.

The idea was to build a small, efficient team composed of a lab field gemologist to find ways to access the mines and collect reference samples; an education field gemologist to help take photos, work on a report and collect data for education; and finally, a videographer to document the whole adventure.

Although Mogok is accessible again, people are not free to go there. The Myanmar government requires travelers to get a permit to visit the gem-producing and trading area. A government-accredited guide must also travel with the group. Pardieu asked one of his friends, Jean Yves Branchard from Ananda travels in Yangon, to deal with the permits, guide and hotels.

He asked Jordan, one of his oldest friends in Mogok, to make arrangements to visit the mines. He met Jordan met in in 2000 when he studied gemology in Yangon and the two visited Mogok several times together until January 2005 when the Myanmar authorities stopped allowing foreigners in Mogok and the other gem-producing areas in Myanmar.

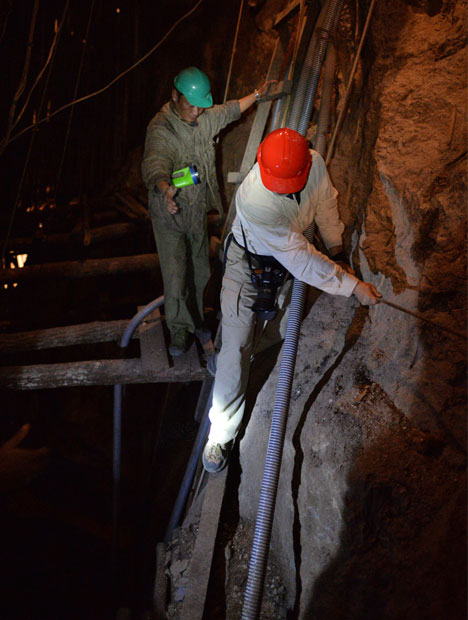

“Traversing a rock wall in a ruby mine in Mogok that reaches a depth of 300 meters, gives you have a heightened sense of focus,” said Lucas, in red helmet. He found the activity much different from his desk work in Carlsbad. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA

Pardieu, Lucas and their cameraman Didier Gruel focused on improving their stamina for the physically grueling trip. The challenge in Mogok is not about long hours walking in jungle or remote mountain areas, Pardieu said, it is in navigating the underground ruby mines that could be several hundreds of meters deep. Places like Kadoke Tad consist of an impressive network of wooden ladders that look like the underground Goblin kingdom in the movie “The Hobbit,” he said.“Just take your time. Don’t try to move like the locals move: Each step, make sure you get a sure footing before you make the next step,” Lucas said after visiting these mines. “It’s better to be slow and sure than have a fast fall.”

The group visited numerous mines, markets and cutting areas practicing what Pardieu calls “‘doing gemology with your eyes and not your ears,” meaning getting the information yourself at the source, not secondhand from others. They also absorbed the culture and personality of the people and the beauty of their temples and pagodas.

“The time we spent together on previous field expedition was useful to improve our team’s efficiency,” Pardieu said. “Communication was easy and efficient. We were ready for the Mogok experience and everyone went home safely with great samples, thousands of photos, hours of video footage and wonderful memories.”

This is success by any definition of a great field expedition.