Bargaining for Gems in Chanthaburi

April 30, 2013

At the Chanthaburi gem market in southeastern Thailand, where buyer and seller often speak no common language, the calculator is a universal translator.

Buyers sort through a prospective parcel of polished ruby at the Chanthaburi market while the runner awaits their offers. For buyers who don’t speak Thai, the calculator serves as the universal translator.

Chanthaburi’s gem trade dates back centuries—accounts of mining and trading there began in the 15th century—and today its gem market remains one of the world’s largest and liveliest.Thailand is one of the world’s leading colored gemstone cutting and trading centers. It exported an estimated $650 million worth of gemstones during 2012—about half of that sapphire, according to the Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand. While most traders keep their export offices in Bangkok, the traditional center of the colored stone industry, the place where nearly all of the cutting is done, is Chanthaburi. This town of about 30,000 lies 150 miles southeast of Bangkok, near the old ruby and sapphire mining area of Pailin on the Cambodian border.

A buyer checks a large parcel of blue sapphire in the open-air Chanthaburi market while the dealer holds the rest of the lot.

The Chanthaburi gem market is a relatively quiet place during the week, with a few dozen dealer shops on narrow Si Chan Road offering loose gemstones, gold settings, and equipment, such as electronic scales, lighting, and loupes and tweezers. But the weekend is when the market truly comes alive, spilling into the neighboring streets and alleys. Beginning at 10 am Friday, hundreds of dealers from around the country and many parts of the world set up makeshift stands with scales, calculators and, of course, gems. Within 30 minutes, the streets are teeming with buyers, brokers, sellers and an occasional tourist. The trading continues until dusk. Unlike traditional markets, most of the people sitting at the tables and desks are buyers, not sellers.

Some of the buildings along Si Chan Road are weekend stone exchanges where buyers and sellers don’t have to worry about the sudden downpours that can arrive at any time during the spring and fall.

The center of the action is at the intersection of Si Chan Road and Thetsaban Road, where the streets serve as an impromptu gem exchange. Buyers will find a seat at a table, sometimes posting a sign listing their wants, and wait for brokers or dealers. Runners working with the dealers dash from table to table, taking orders, showing gems and carrying price offers back to their bosses. Some dealers hurry to intercept the buyers before they get to the tables so they don’t have to pay commission to the table owners.What’s for sale? Not surprisingly, a vast majority of the dealers were offering ruby and sapphire of all colors—some for as little as $2 or $3 per carat. Are treatments disclosed? The price is the disclosure, said one dealer who’d stopped by to show a parcel of ruby. Sellers also showed spinel, various colors of tourmaline, tsavorite and spessartite garnet, and even amethyst and citrine. Between the gem vendors and exchanges is a veritable smorgasbord of street food, with vendors offering noodles, barbecue chicken, mangoes and soup bowls.

Si Chan Road leads to the gem market in Chanthaburi—the street lamps pay tribute to the main commerce in this city of 30,000 inhabitants.

On the side streets behind the market are dozens of “burners,” operations that apply heat and other treatments to gemstones. Most of these have no sign out front but are well known to the local trade.Veteran dealers say the trading at the market is quieter than a decade ago. They blame Western governments’ sanctions on Myanmar and the general economic malaise in many key consuming markets. But the market has survived transitions before. Indeed, Chanthaburi’s gem trade has been rejuvenated to some degree by diffusion treatments that can turn unattractive (and unsellable) corundum into low-cost yellow sapphire. Because of this, at least 10 mine sites are now in operation near Khao Ploy Waen and Ban Ka Cha. Additionally, one site produces black star sapphire that is not treated.

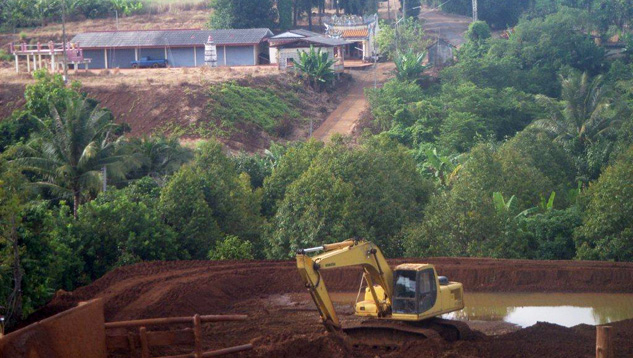

The Chanthaburi province was once a prolific producer of ruby and sapphire. This mine, about 10 miles from the city, is a source of yellow sapphire.

Despite the slower sales, dealers such as the woman in the floral dress believe Chanthaburi will always have a place in the world gem business, because the skills and the infrastructure vital to the industry are still concentrated here.