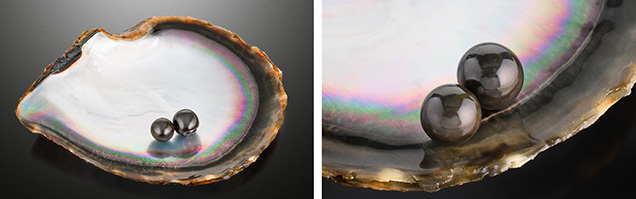

Two Black Non-Nacreous Bead Cultured Pearls from Pinctada margaritifera

The laboratory in Carlsbad recently received for identification two black pearls, one near-round and one button. The near-round pearl weighed 15.16 ct, while the button weighed 22.19 ct, with dimensions of 13.17 × 13.02 mm and 14.81 × 14.52 mm, respectively. Both displayed a similar vitreous luster and a non-nacreous surface appearance (figure 1). The button-shaped pearl also exhibited a nacreous surface on a small circled area at the base (figure 2). Microscopic examination using fiber-optic illumination revealed that the non-nacreous surface was composed of a mosaic or cellular pattern, resulting from the acicular nature of the individual calcite crystals. Some fine surface lines were also present in random directions across the cellular structures (figure 3). These cellular structures resembled those commonly observed on pen pearls from the Pinnidae family (N. Sturman et al., “Observations on pearls reportedly from the Pinnidae family (pen pearls),” Fall 2014 G&G, pp. 202–215).

A Raman spectrometer with 514 nm argon-ion laser excitation was used to examine the surface composition. The non-nacreous surfaces of both pearls showed a calcite spectrum with peaks at 712 and 1085 cm–1, and aragonite peaks at 705 and 1085 cm–1 were recorded on the nacreous surface at the circular base of the button-shaped pearl. Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence chemical analysis showed low levels of manganese and high strontium content, confirming the pearls formed in a saltwater environment.

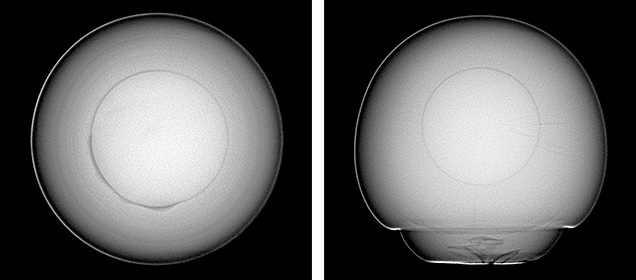

The large size, black bodycolor, and cellular structure of the pearls looked similar to the unusual non-nacreous natural pearls reportedly from Pteria species (S. Karampelas and H. Abdulla, “Black non-nacreous natural pearls from Pteria sp.,” Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 35, No. 7, 2017, pp. 590–592) and a bead cultured (BC) pen pearl (Winter 2014 GNI, pp. 305–306) previously reported. Under long-wave ultraviolet radiation (365 nm), the pearls exhibited very weak yellow fluorescence that differed from the strong orangy red fluorescence observed in non-nacreous Pteria pearls. Real-time microradiography (RTX) revealed a round bead nucleus in the center of both pearls, indicating BC pearl origin (figure 4) similar to the previously reported BC pen pearl. Nevertheless, the ultraviolet/visible reflectance spectrum collected on the button pearl’s nacreous surface showed a typical reflectance feature at 700 nm, a key mollusk identification feature attributed to Pinctada margaritifera pearls (K. Wada, “Spectral characteristics of pearls,” Gemological Society of Japan, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1983, pp. 3–11, in Japanese). The reflectance features at 405 and 495 nm normally observed in naturally colored gray to black nacre of P. margaritifera shells were also present. Combining the cellular surface structures, BC origin, saltwater environment, and spectroscopic characteristics, we were able to conclude that both were non-nacreous BC pearls from the P. margaritifera mollusk.

All pearls are formed from calcium carbonate (CaCO3) polymorphs such as aragonite and calcite together with organic substances as well as water. The most common form of CaCO3 in pearls is a layered structure of aragonite platelets. This structure is the reason pearls display a nacreous surface and pearly luster. A non-nacreous surface indicates a pearl that formed from CaCO3 but not with an aragonite platelet microstructure. Conch and Melo pearls are non-nacreous pearls that possess an aragonite fibrous or lamellar structure that display flame-like surface patterns. Scallop pearls are non-nacreous pearls made of calcite in a honeycomb patchwork of cells. Pen pearls mentioned previously are another type of calcite pearls with a cellular structure.

These two special occurrences are the first non-nacreous BC pearls from P. margaritifera identified by GIA. Cultured pearls from this mollusk, both BC and non-bead cultured, typically display a nacreous surface and are often referred to as “Tahitian” pearls in the market. Genetics is probably the most important factor influencing the biomineralization of a pearl, yet many other factors can be involved such as water environment and health of the mollusk. Organic substances also play an important role in the biomineralization process (C. Jin and J. Li, “The molecular mechanism of pearl biomineralization,” Annals of Aquaculture and Research, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2017, p. 1032). In nature, many living organisms elaborately control the formation of biominerals for specialized functions such as mechanical support, protection, and mineral storage. Some mollusk species may produce different structures under certain circumstances.