Two Pearls of Indian Cultural Significance

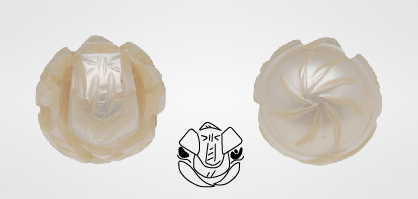

In India, pearls (also known as moti or mukta) and pearl-adorned jewelry have historically been coveted by the affluent and served as symbols of cultural importance for centuries. GIA’s Mumbai laboratory has tested various jewelry items set with pearls that were not only artistic in their design but also of great symbolic and religious significance. Two recent submissions consisted of pearls fashioned into the likenesses of Indian deities (figure 1). The first was skillfully crafted to resemble Lord Hanumana, an Indian deity from the epic Ramayana bearing the likeness of a vanara (an ancient race of forest-dwellers). The ornament had a total weight of 24.91 g, and its surface was partially drilled in several positions. Yellow metal fittings set with green, white, yellow, and black enamel formed the head, eyes, body, and striped tail. A translucent red stone set on the pearl formed the tongue of the deity (figure 2, left). This baroque pearl was white and light gray in color with orient and measured approximately 33.70 × 32.98 × 24.64 mm. When viewed under 40× magnification, its surface showed typical nacreous structure with overlapping aragonite platelets, and minor surface openings were present on some areas. Most of the surface had good nacre condition, but a few small areas of the nacre were damaged or worn, and remnants of an adhesive glue were visible around some of the decorative enamel inserts.

Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) spectrometry analysis of the pearl showed manganese levels below the detection level of the instrument and a higher strontium content of 1188 ppm. In addition, an inert reaction to X-ray fluorescence (XRF) confirmed saltwater origin. A moderate greenish yellow reaction was observed under long-wave ultraviolet radiation, and a weaker reaction of a similar color was noted under short-wave UV radiation. Such fluorescence reactions in nacreous saltwater pearls are often associated with pearls from the Pinctada-species mollusk. Real-time microradiography (RTX) imaging revealed the presence of a very large void that appeared to have been partially filled with a foreign material (figure 2, right). The clearest evidence of the void was observed within the ornament’s head as a dark gray area beneath the nacre layer. The outline of this void was consistent with the external shape of the pearl, but the filling material partially masked the void in RTX and made it harder to see the complete structure clearly. (The radiopaque areas visible on the microradiographs represent the adornments decorating the pearl.) While large voids are more often associated with non-bead cultured pearls, the shape and form of this void resembled those associated with natural pearls. Hollow pearls are often filled (wholly or partially) with a variety of materials including wax, metal, resin, cement, and shell to increase the weight and inflate the perceived value (Winter 2022 Lab Notes, pp. 480–481). In the case of older pearls such as this one, filling can provide enough solid material within the pearl to support all the metal adornments, and it can also improve the durability of the item.

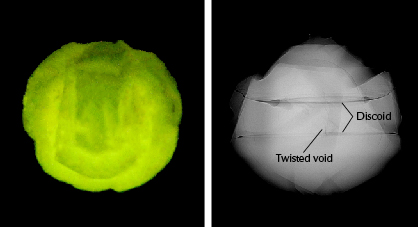

Also submitted was a pearl portraying Lord Ganesha (figure 1, right). The white undrilled, button-shaped pearl weighed 6.27 ct and measured 10.59 × 10.21 × 9.18 mm. Its surface was carefully carved to resemble the Indian deity, with the head of an elephant and the seated body of a man on the front and a swirling pattern on the back (figure 3). EDXRF analysis results showed a high manganese content of 598 ppm and relatively low strontium levels at 376 ppm. These readings were supported by a strong yellowish green fluorescence reaction when exposed to optical XRF (figure 4, left), indicating the pearl was from a freshwater environment. RTX imaging revealed the presence of a small twisted void, along with discoid-like features (figure 4, right) typically seen in non-bead cultured freshwater pearls (K. Scarratt et al., “Characteristics of nuclei in Chinese freshwater cultured pearls,” Summer 2000 G&G, pp. 98–109).

The transformation of pearls into valuable pieces of art is a specialized skill. Indian artists have mastered this ability and can transform pearls into symbolic pieces that have a special connection to ancient Indian scriptures. The laboratory staff at GIA in Mumbai continue to examine intriguing pearls of historical and cultural significance in India.