Quarterly Crystal: Heavily Etched Blue Beryl Crystals Reportedly from Pakistan

In previous Micro-World columns, the Quarterly Crystal entry has showcased exceptional crystalline specimens masterfully crafted by geological forces. In some cases, however, it is the darker destructive forces of nature that produce a fine mineral specimen. In 2018, Raza Shah (Gems Parlor, Fremont, California) began unearthing heavily etched dark blue beryl crystals from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in northern Pakistan. Bryan Lichtenstein (3090 Gems, San Francisco, California) submitted three of these crystals to GIA’s Carlsbad lab for identification services (figure 1; see also B.M. Laurs and G.R. Rossman, “Dark blue beryl from Pakistan,” Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 36, No. 7, 2019, pp. 583–584).

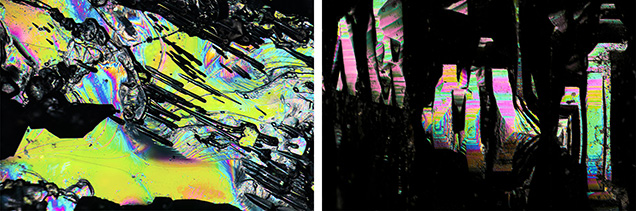

The hexagonal barrel shape that must have characterized the crystals in their initial state is still apparent despite the heavy etching. The geological conditions responsible for beryl growth apparently persisted long enough for many of these crystals to grow to extreme sizes; the largest recovered so far weighs 236.8 g. At some point, these crystals appear to have fallen out of equilibrium with their natural environment and the beryl started dissolving back into the earth. Microscopic observation of the corroded surfaces shows how the dissolution process is controlled by the beryl crystal structure, with dissolution pits and the skeletal remnants of the beryl constrained by the underlying crystal lattice. Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy can be used to highlight both growth and dissolution features in the same image (figure 2). While Pakistan is an important source of aquamarine crystals and gems, this heavily etched dark blue aquamarine is truly a unique find.