Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals

The American Museum of Natural History in New York City has reopened one of the most beloved spaces for gem enthusiasts with the unveiling of the Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals on June 12, 2021. After a four-year closure, the 11,000-square-foot halls, which house more than 5,000 specimens sourced from 98 countries, have been completely redesigned and reinstalled to tell the intriguing story of how mineral diversity arose on our planet. This exciting public event reflects the reopening of New York City.

The American Museum of Natural History has a long-standing history with minerals and gems that dates back to its founding in 1869. In the 45 years since the previous iteration of the gem and mineral halls opened, the scientific fields of mineralogy and geology have advanced significantly, and the new design reflects these advancements. The halls were organized by Dr. George E. Harlow, curator of the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, to showcase to the public the current scientific understanding of gems and minerals, the geological conditions and processes by which they form, and introduce the relatively novel concept of mineral evolution.

Mineral evolution, one of the central themes, seeks to explain how more than 5,500 mineral species came into existence when there were no minerals for hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang. The new halls show how changing conditions on Earth allowed more chemically diverse minerals to arise. They highlight one of the most important changes, which is the evolution of life that filled the atmosphere with free oxygen, enabling colorful, highly oxidized minerals. These are the same colorful minerals we associate with the gemstones humans have used to decorate themselves for thousands of years.

The redesigned space no longer resembles a simulated subterranean mine, with the multi-leveled carpeted interior that the previous iteration was known for. Instead, an open-floor concept allows visitors to wander seamlessly between the different displays and exhibits. It has three main divisions: the Mineral Hall, the Gem Hall, and the Melissa and Keith Meister Gallery for temporary exhibitions.

Entering the Mineral Hall, the visitor is welcomed by a pair of towering amethyst geodes that formed nearly 135 million years ago (figure 1). The scale and rich purple color of the massive geodes command attention and set the tone for the rest of the space. Behind the geodes, the center of the Mineral Hall contains mineral specimens organized by formation environment: igneous, pegmatitic, metamorphic, hydrothermal, and weathering. Highlights include the Singing Stone, a massive block composed of blue azurite and green malachite that was collected in 1891 from Bisbee, Arizona (figure 2), and a 14,500 lb. slab from upstate New York that is studded with garnets measuring up to one foot across (figure 3).

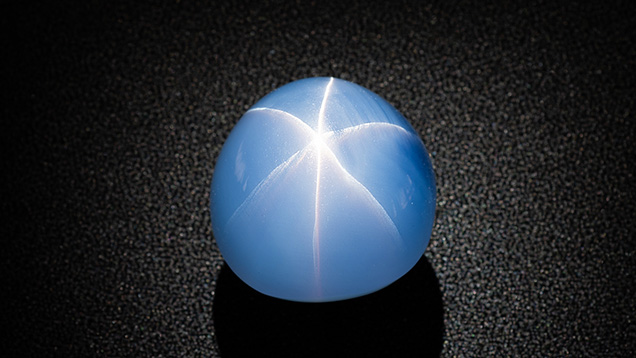

The west wall of the Mineral Hall has a running display dedicated to the systematic classification of minerals. The display contains 659 specimens arranged by chemical composition, increasing in complexity across the wall. An interactive periodic table that can be used to explore forming minerals stands at the center of the west wall. The four corners of the Mineral Hall explore the overarching scientific concepts of minerals, from their evolution and diversity to their properties and how they have been used by humans from prehistory to the present day. Adjacent to the gallery of minerals and light is the Gem Hall. It features a dazzling display of nearly 2,500 objects, including precious stones, carvings, and jewelry from the museum’s world-class collection. Highlights include the 563 ct Star of India (figure 4), the largest gem-quality star sapphire known, and the 632 ct Patricia emerald, the largest gem-quality emerald reported from the Chivor mine in Colombia (figure 5).

In addition, the Melissa and Keith Meister Gallery is a rotating exhibit gallery newly added to the Halls of Gems and Minerals. Beautiful Creatures, curated by jewelry historian Marion Fasel, features animal-themed jewelry created over the last 150 years. The exhibit included more than 100 jewels from the world’s great jewelry houses organized into three categories: land, water, and air. Its time frame coincides with the founding of the American Museum of Natural History in 1869 and explores the extraordinary diversity of the animal kingdom and the inspiration that it has provided for jewelry designers. Beautiful Creatures is on display through September 19, 2021.