Occurrence of Petrified Woods in the Russian Far East: Gemology and Origin

Petrified woods are used all over the world as an excellent material for souvenirs, jewelry, and spectacular collectible pieces. A new occurrence of petrified wood was discovered in 2014 in the Primorsky Krai region of the Russian Far East, near the village of Kiparisovo. The fossils were found in the northwestern part of a sand and gravel quarry, at the contact of rhyolitic volcanic ash tuffs and basalts overlapping them. The sample sizes varied from several centimeters to two meters.

Local jewelers started using the wood fossils as stands for souvenirs (figure 1) and polished collectible samples. The petrified wood appeared in regional jewelry stores and attracted Chinese tourists’ attention, creating demand for the raw material from China’s market.

More than a hundred samples were studied at the Analytical Center of the Far Eastern Geological Institute of the Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (FEGI FEB RAS). We examined the mineral composition, structure, and gemological characteristics using standard gemological equipment, a Nikon E100 POL optical microscope, and a MiniFlex2 X-ray diffractometer (XRD). Several examples of petrified wood were found: white, yellowish, marble-like, chalcedony-like, banded, banded chalcedony-like with brownish growth rings, partially carbonized, and black coalified (figure 2).

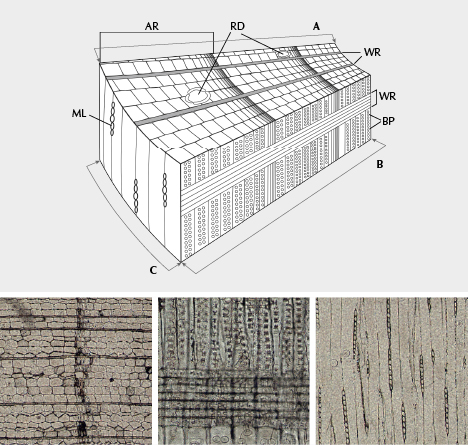

The refractive indices of polished plates ranged from 1.40 to 1.54 in different areas and corresponded to chalcedony, opal, and quartz. Luminescence was weak bluish or greenish under short-wave UV; most samples were inert under long-wave UV. Samples had a fibrous cellular structure. The shape of the cells (tracheids) was angular, rectangular, and sometimes subsquare (figure 3, bottom left). The transections of the samples showed very narrow single-row horizontal wood rays. Vertical resin ducts that looked like white dots were located in the latewood area of the annual rings (vertical dark band) (figure 3, bottom left). On the radial sections of the samples, we observed wood rays (horizontal lines) and bordered pits (round-shaped pores) (figure 3, bottom center). Middle lamellae (chains-like cells) were seen on a tangential section of petrified wood (figure 3, bottom right).

The absence of vessels, the unique type of wood rays and tracheids with bordered pits, the character of the middle lamellae, and the presence of vertical resin ducts indicated that these samples belonged to coniferous plants. X-ray diffraction analysis showed that all the varieties of petrified wood had an opal-cristobalite-tridymite composition.

The geology of the area allowed us to imagine the formation conditions. As a result of catastrophic volcanic eruptions of rhyolitic magmas as glowing ash clouds, and late effusions of mantle magmas, thick layers of volcanic ash and overlapping basalt flows were formed. The basalt lava flows outpoured into the water basin with a temperature exceeding 1000°C. Lavas overlapped the flooded trunks and thick bottom sediments of ash silts. When the basalt melt came into contact with water, the surface of the lava flow instantly quenched with the formation of pillow lavas. The space between the pillow lavas was filled with clastic glassy rocks known as hyaloclastites.

Thus, the flooded trees were under the hyaloclastites and pillow lavas. Some trees, under the weight of a lava flow, had taken a vertical position. Some trunks that sunk in hyaloclasts were charred, while trunks in ash silts remained unchanged. During silicification, the charred parts of the trunks acquired a black color and the uncharred parts became white, light yellow, to brownish (figure 4). Buried trees underwent strong deformation with flattening of the trunks, splitting, and fragmentation of wood.

The main source of silica when replacing the cells of trees by quartz or opal was ash silts. This was promoted by a low-alkaline water-saturated volcanic ash with a high SiO2 content (over 72 wt.%). The silicon-containing aqueous solutions penetrated woods that, under anaerobic conditions, represented local geochemical barriers where precipitation of free silica replacing plant cells occurred. Depending on the concentration of silicon in the solution in plant cells, the deposition of opal, chalcedony, or quartz occurred. The foregoing description allows us to imagine a majestic picture of how Nature created this wonderful combination of the worlds of plants and stones.