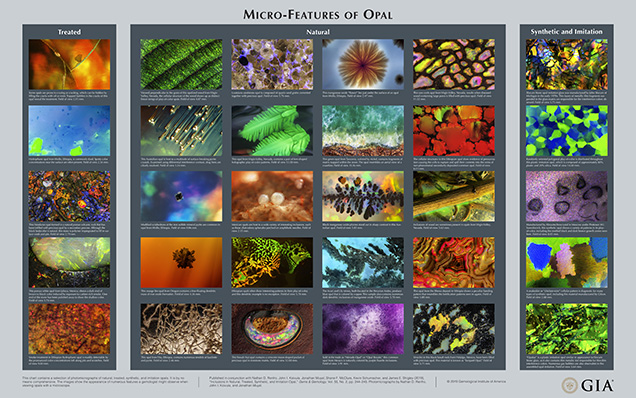

Inclusions in Natural, Treated, Synthetic, and Imitation Opal

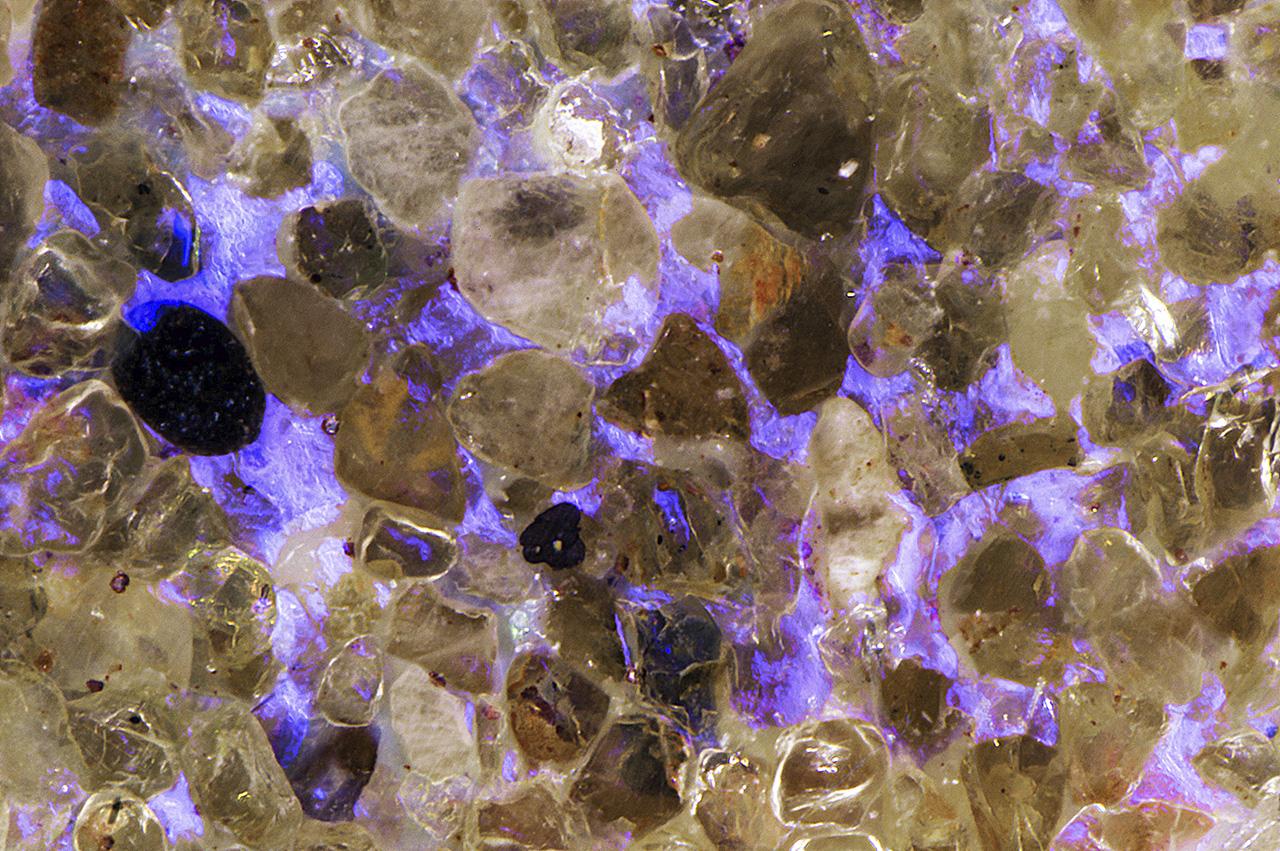

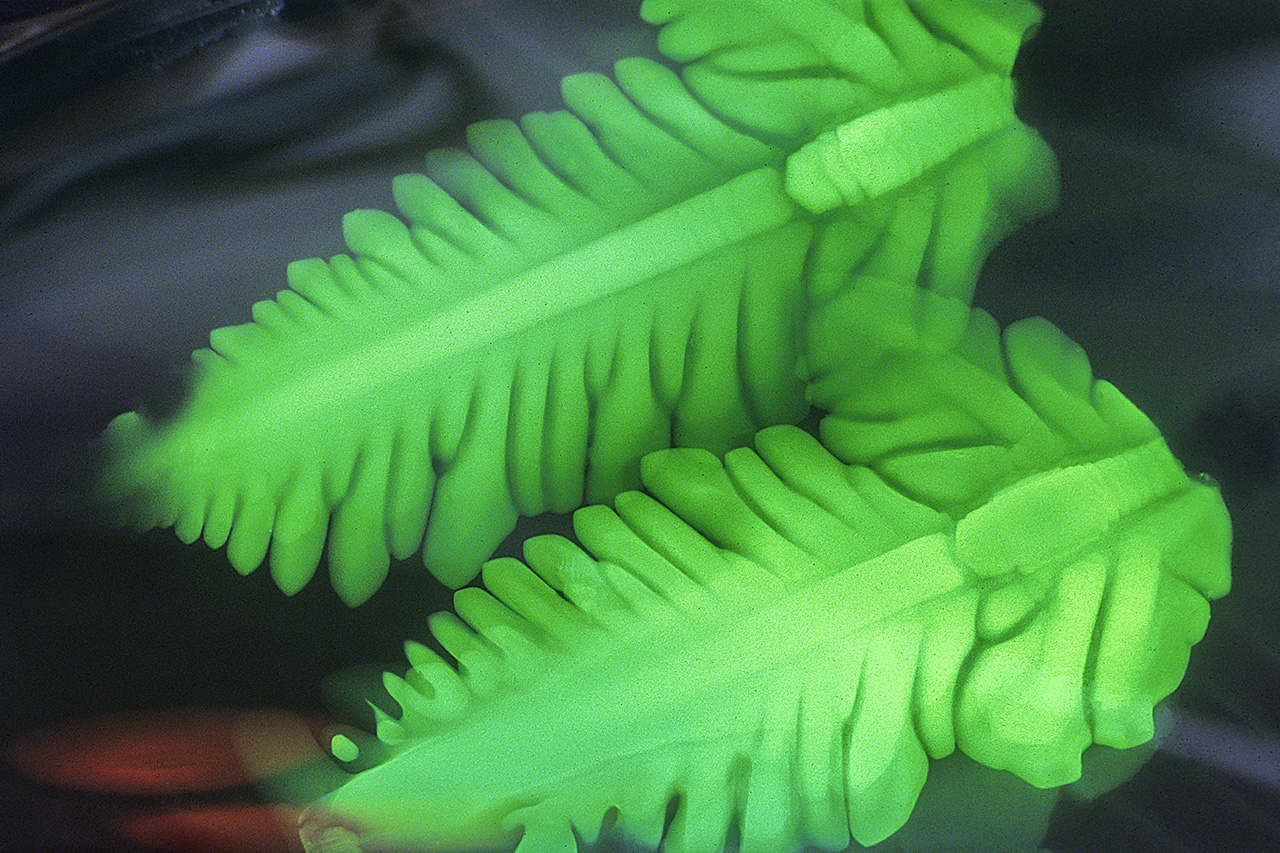

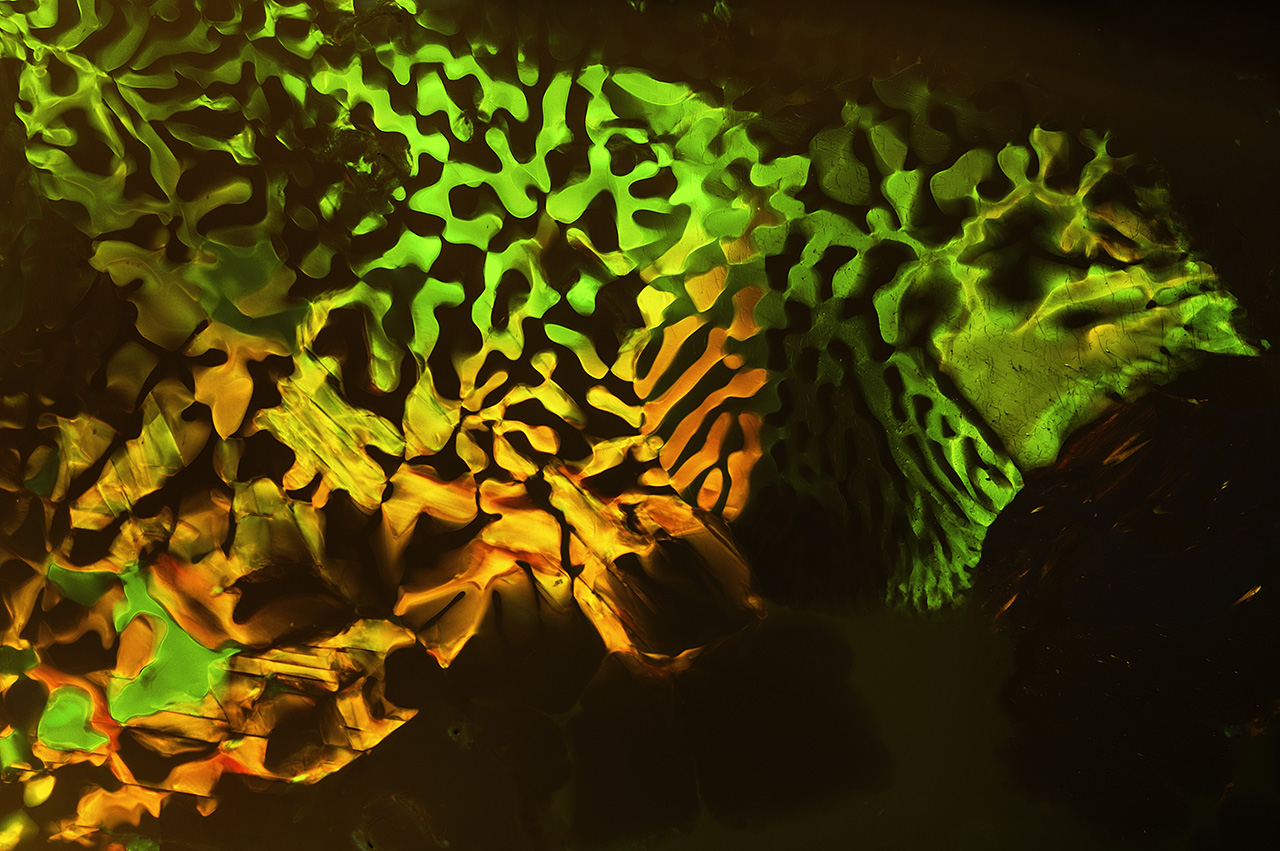

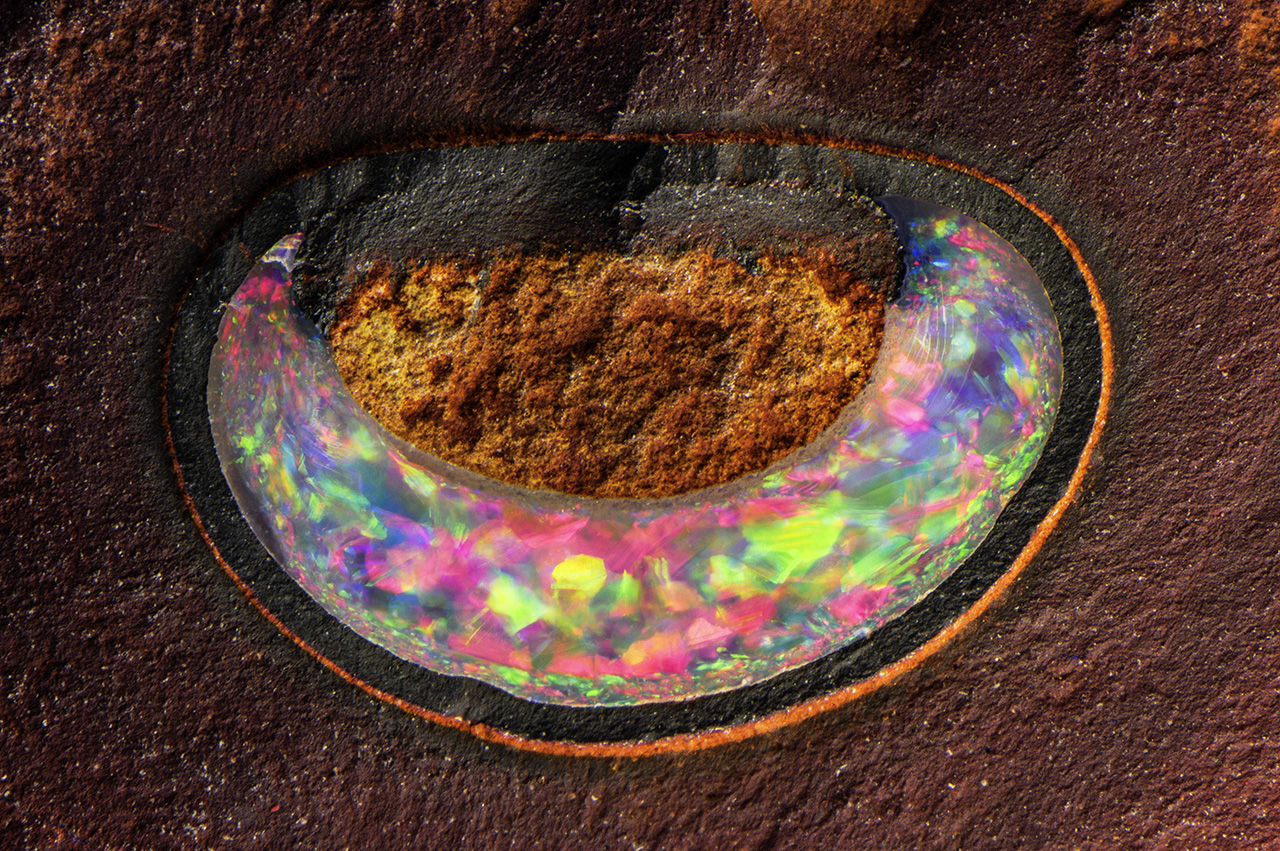

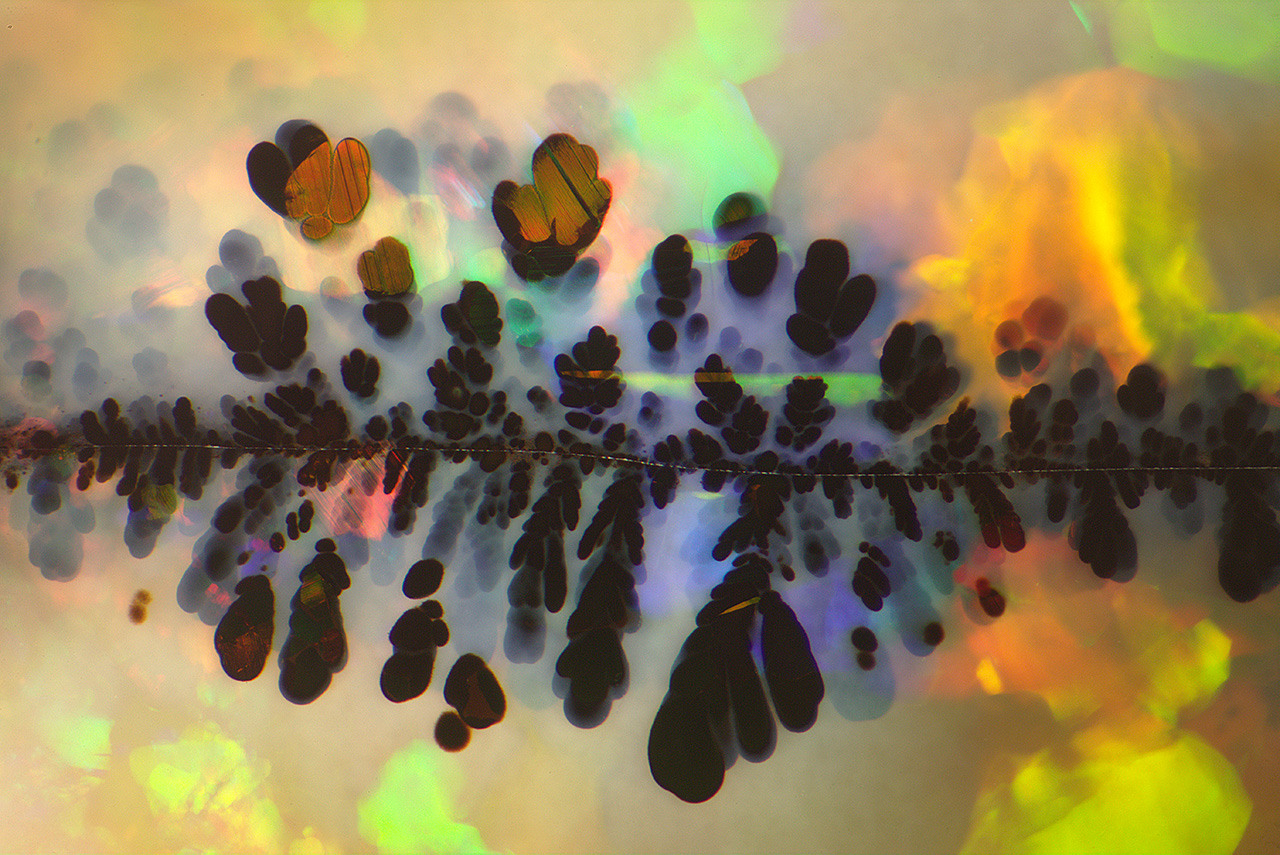

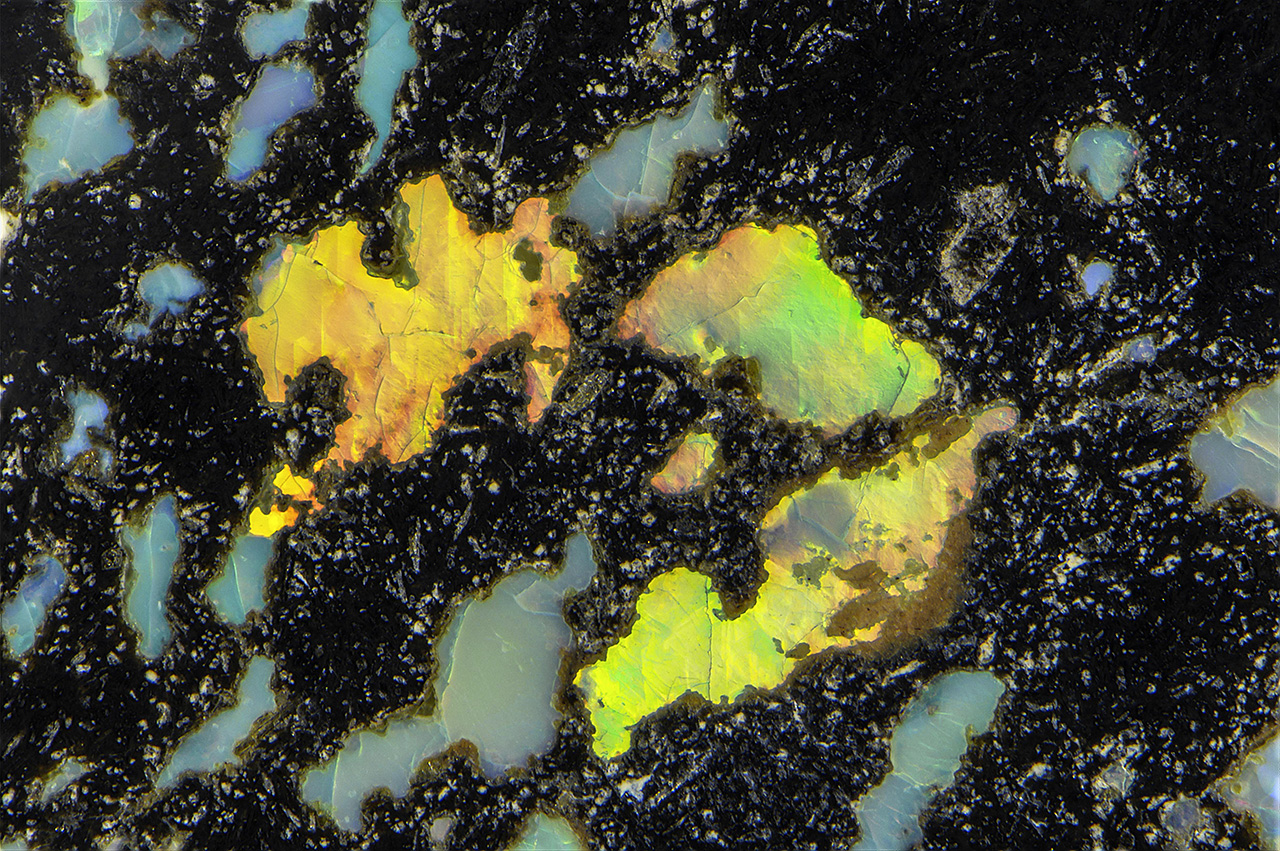

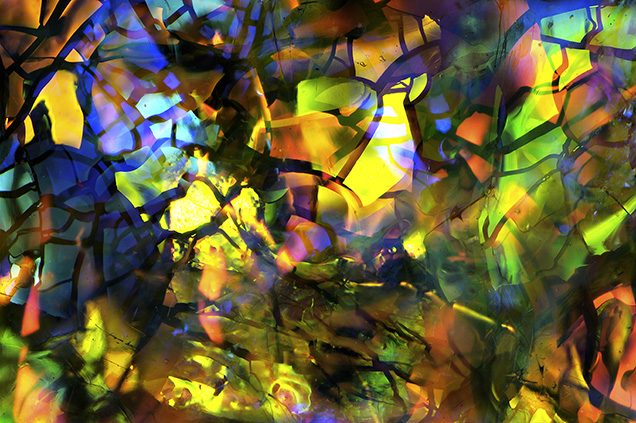

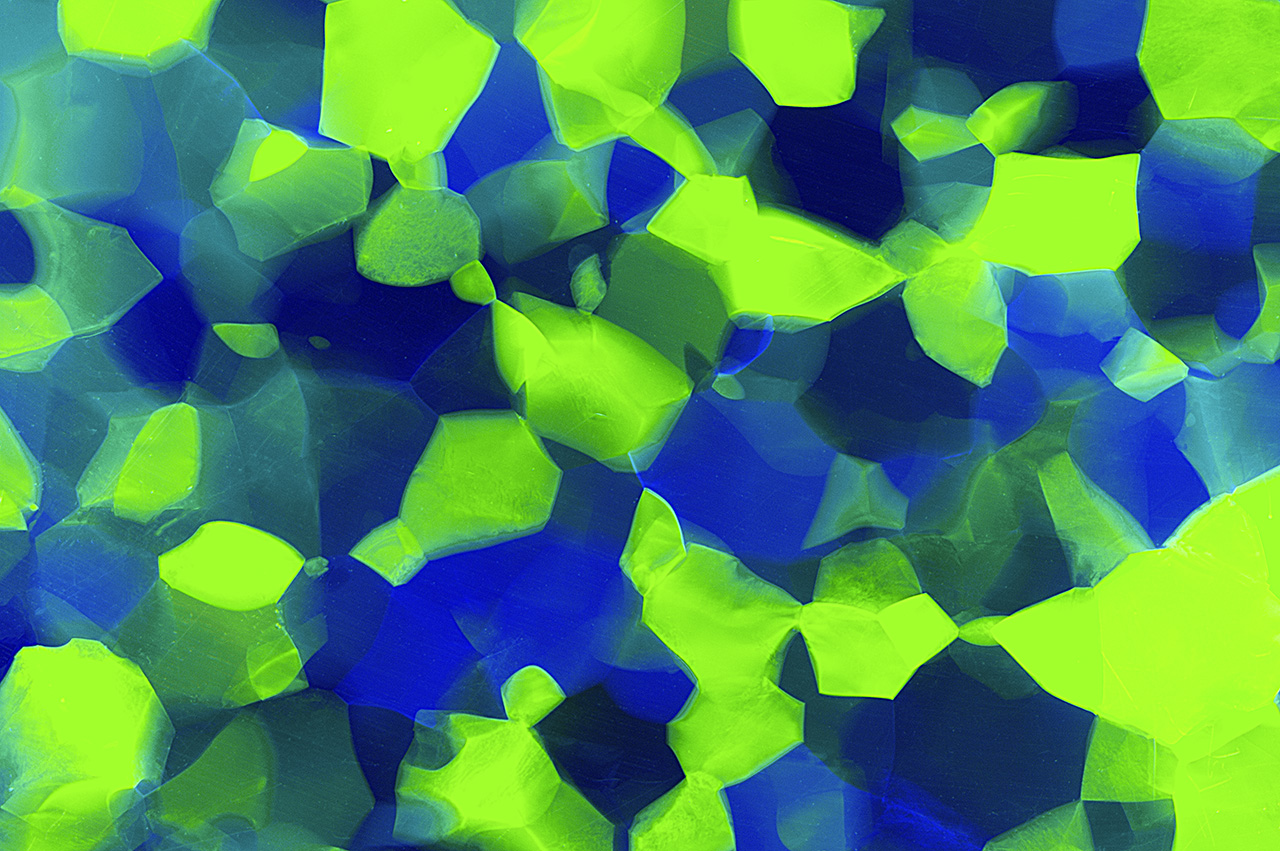

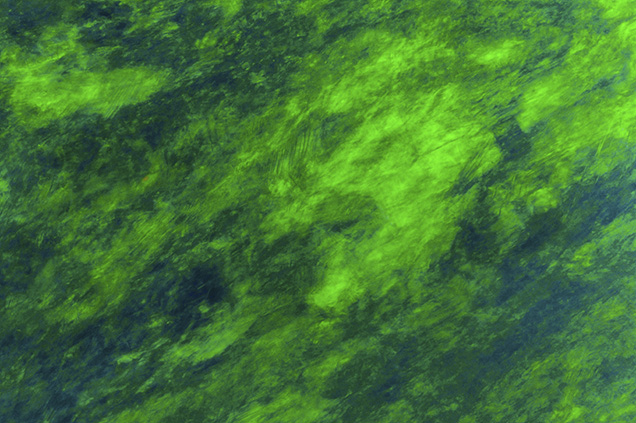

When gemologists think of opals, play-of-color is almost certainly the first characteristic that comes to mind (figure 1). While play-of-color patterns can be extraordinarily beautiful under magnification, opals often contain a vast array of spectacular microscopic features in addition to this phenomenon. In continuing G&G’s series on inclusions, this chart will focus on natural, treated, synthetic, and imitation opals.

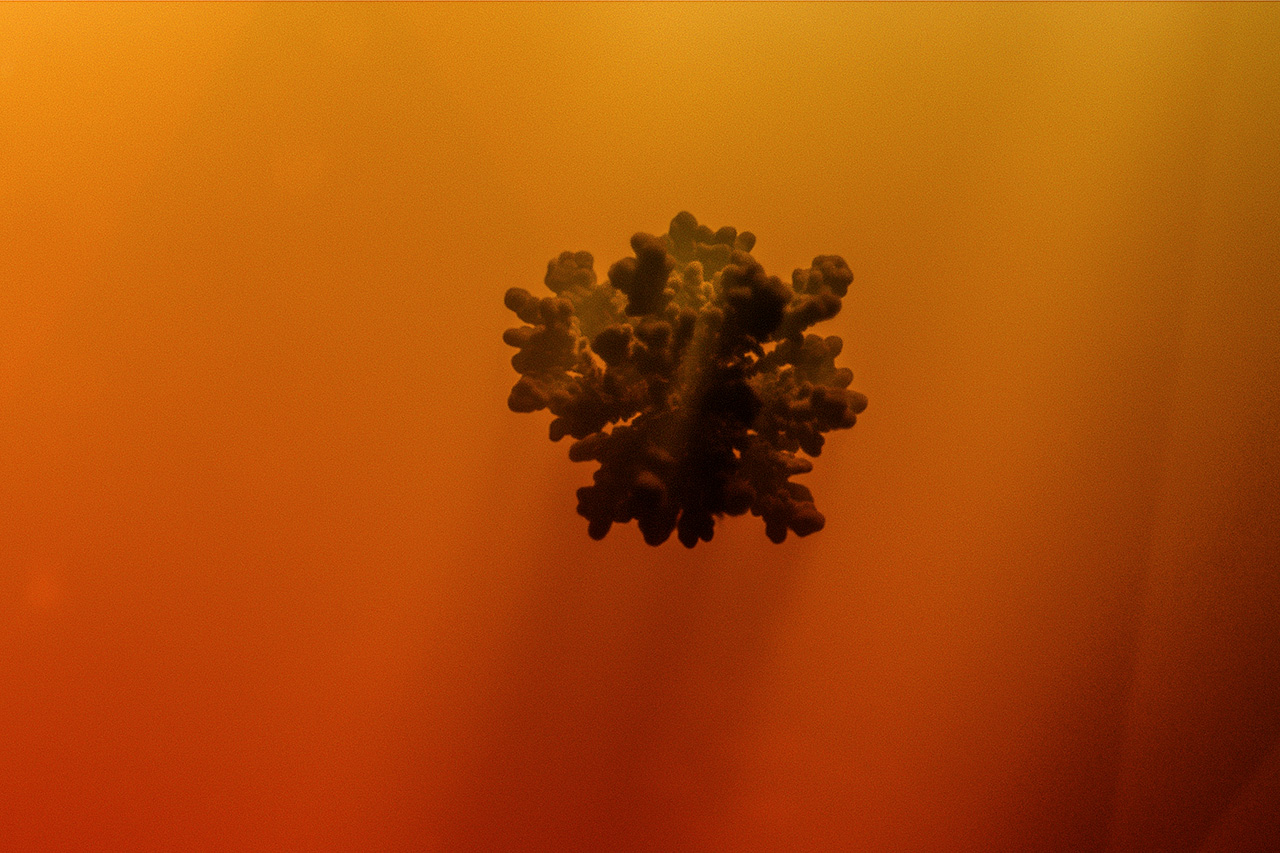

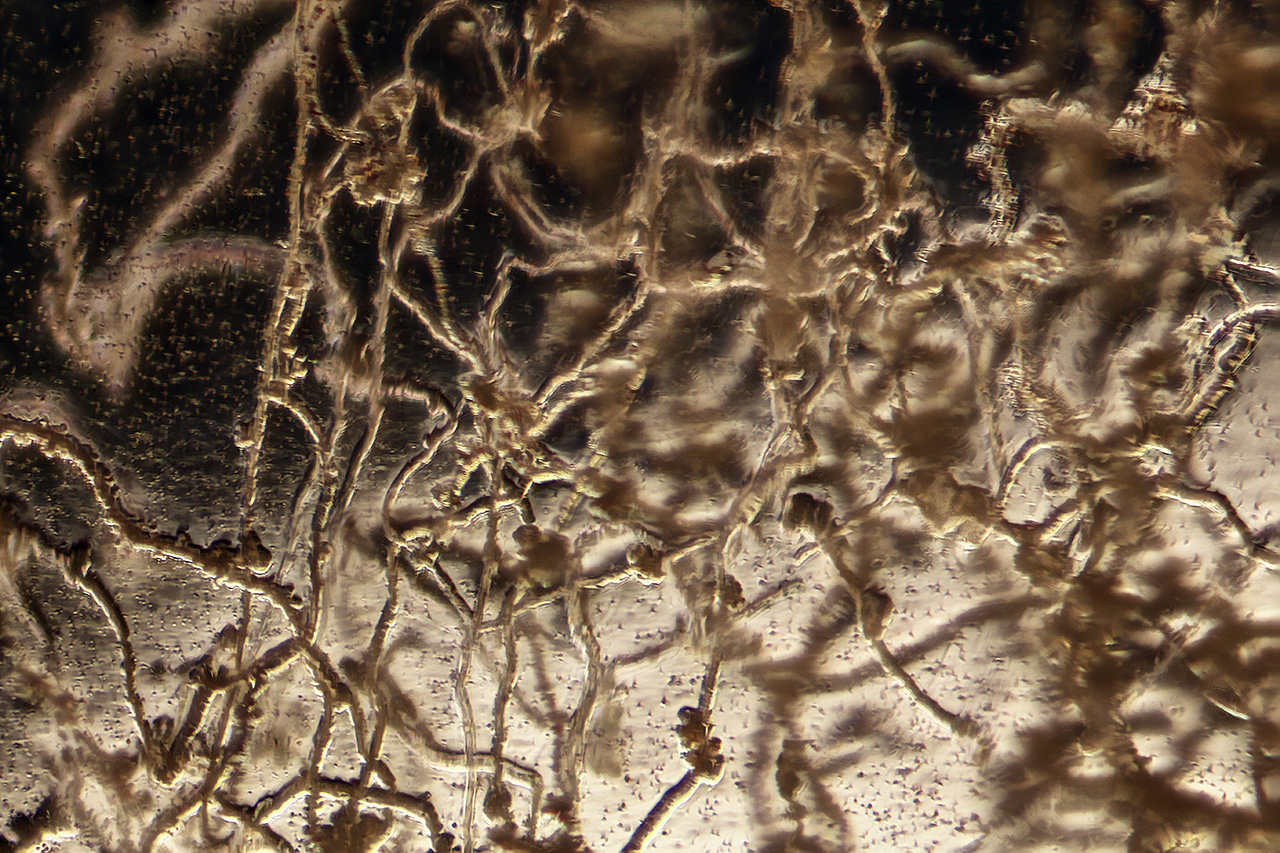

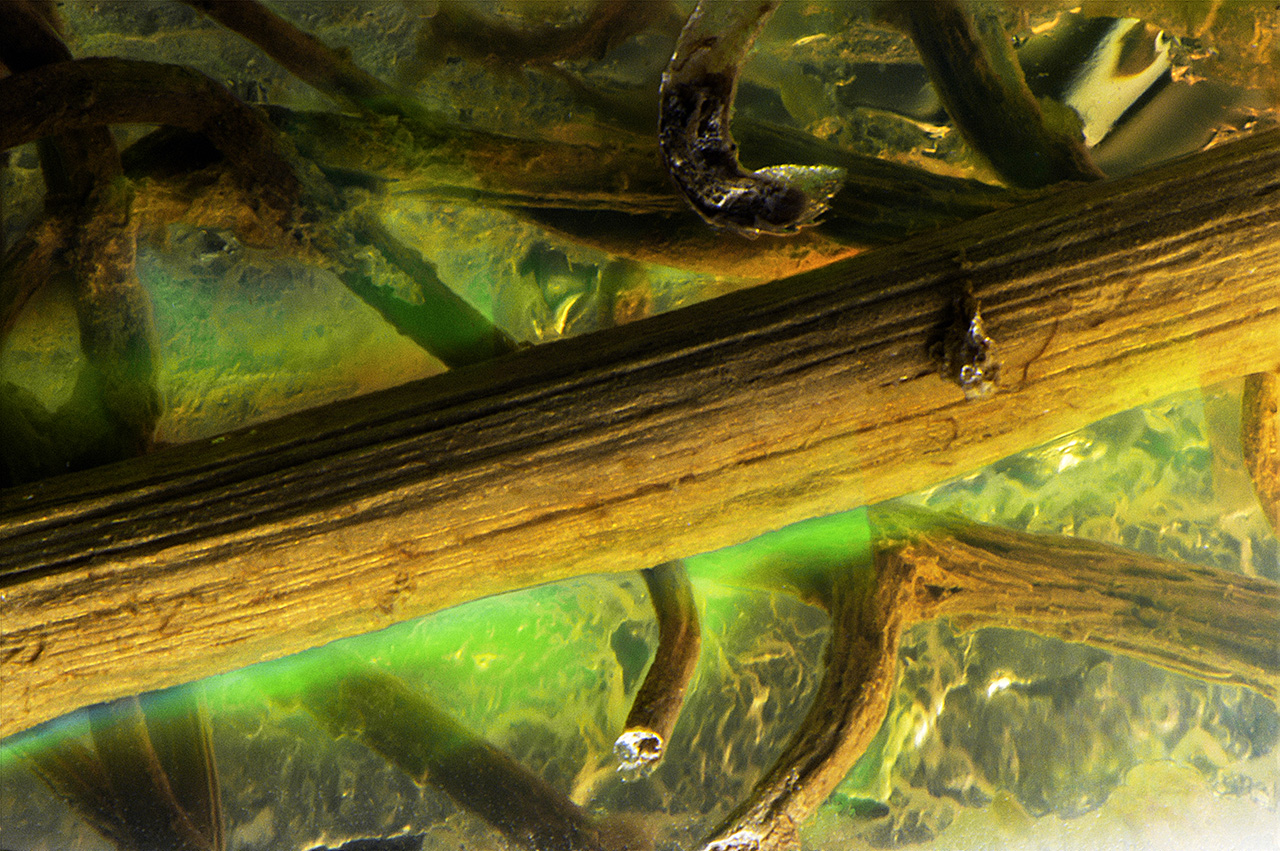

There have been significant developments in the opal industry in recent years with the discovery of opal from Wollo Province in Ethiopia (Rondeau et al., 2010). This deposit produces opals that contain a wide range of interesting inclusions such as fossilized plant material. Opals from Australia also have the potential to showcase spectacular inclusion scenes, from pyrite crystals to black plumes of manganese oxide that stand out in high contrast to the play-of-color phenomenon. Other sources of natural opal that contain visually striking inclusions are Mexico, the United States, Honduras, and Peru.

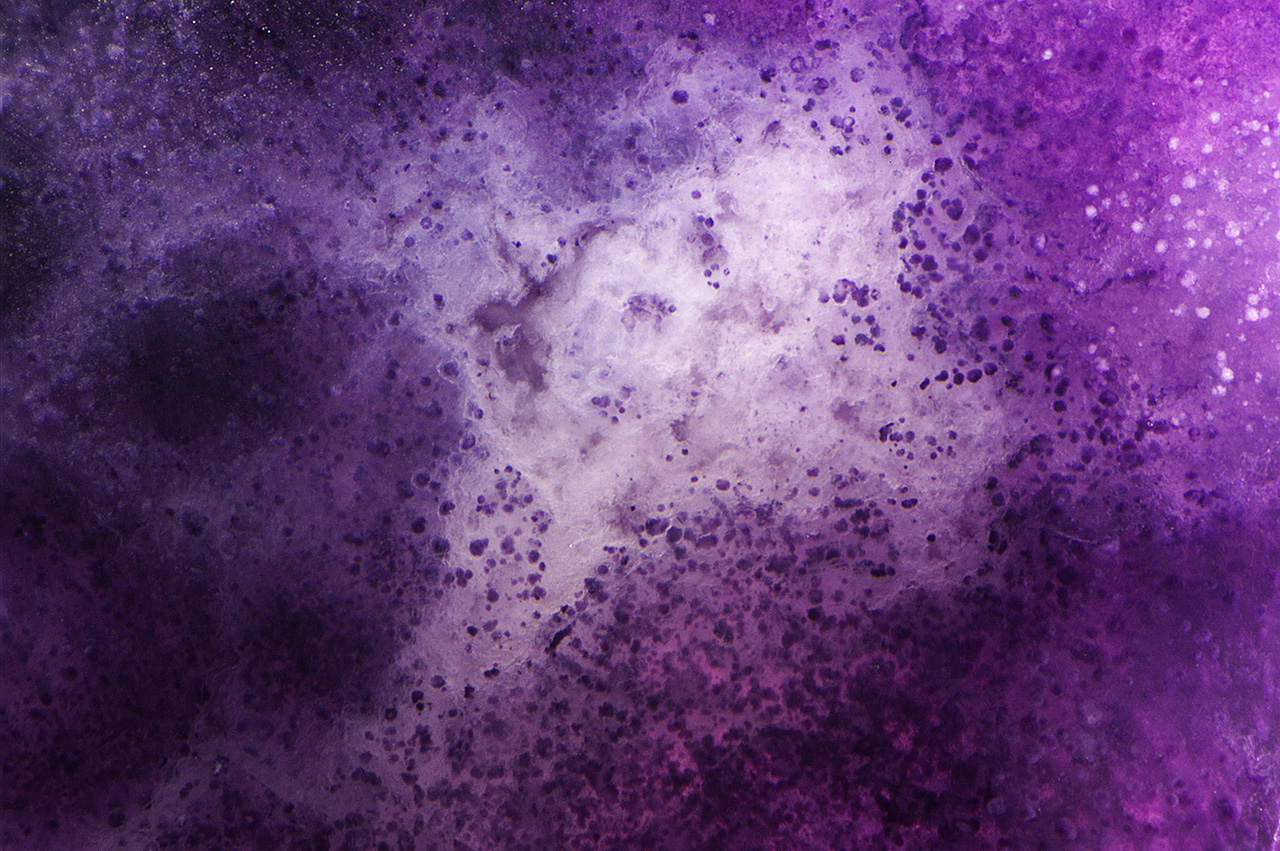

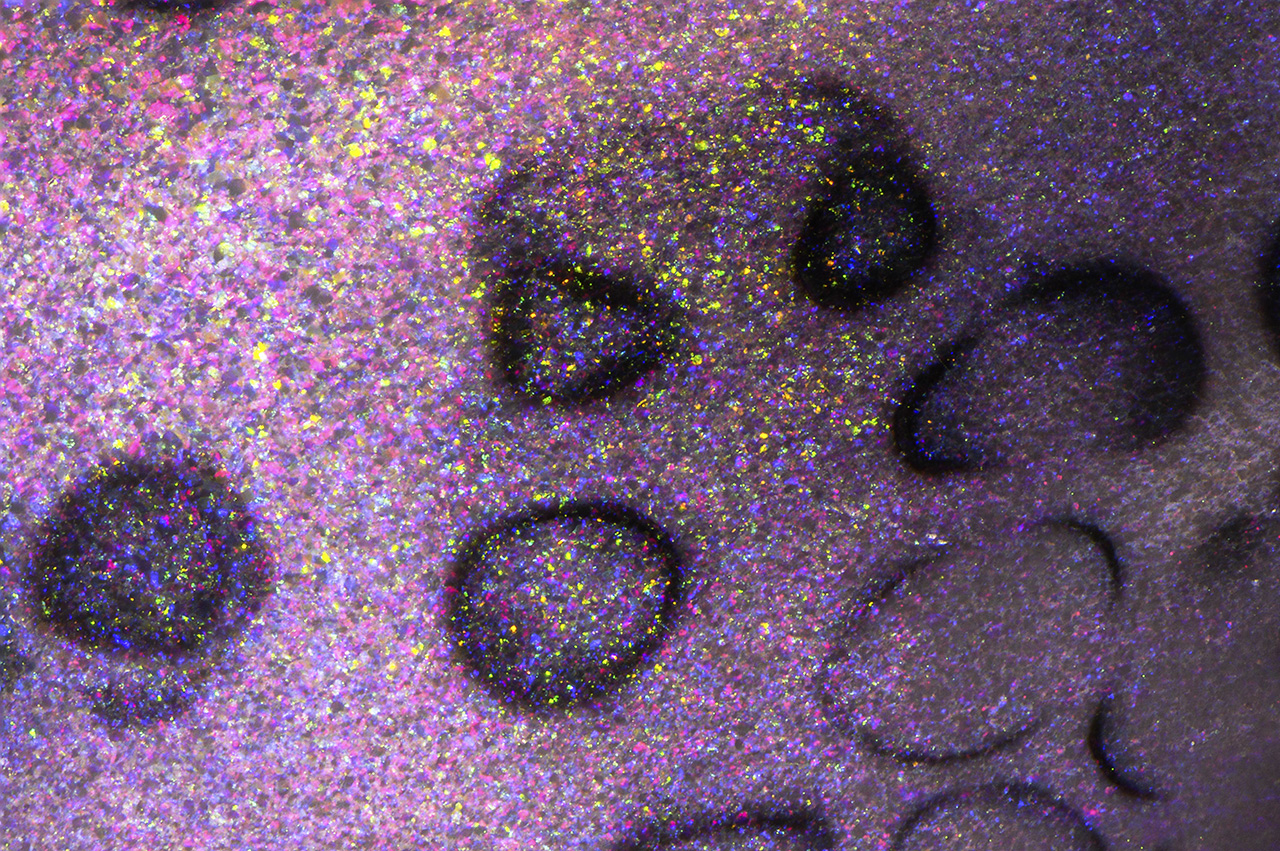

Along with the new Ethiopian deposit came new treatments. The opal from this deposit was hydrophane, which meant it would readily absorb liquids. Soon gem treaters took advantage of this property and began to dye Ethiopian opal a myriad of colors, most notably purple (Renfro and McClure, 2011). This material also proved quite responsive to smoke treatment, which gives it a dark bodycolor (Williams and Williams, 2011). Other traditional opal treatments include color modification by sugar treatment and clarity enhancement by hiding fractures and cavities with resins or oils (Renfro and York, 2011).

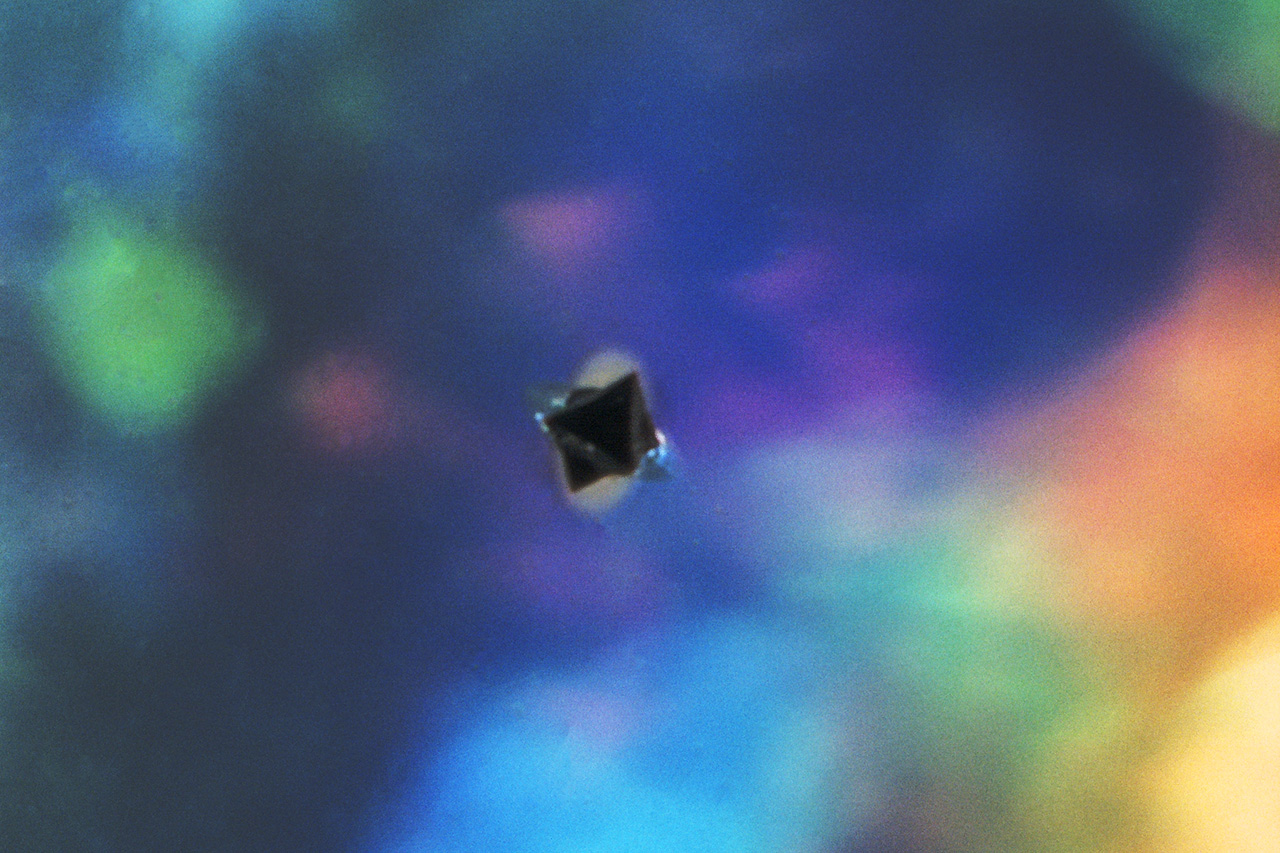

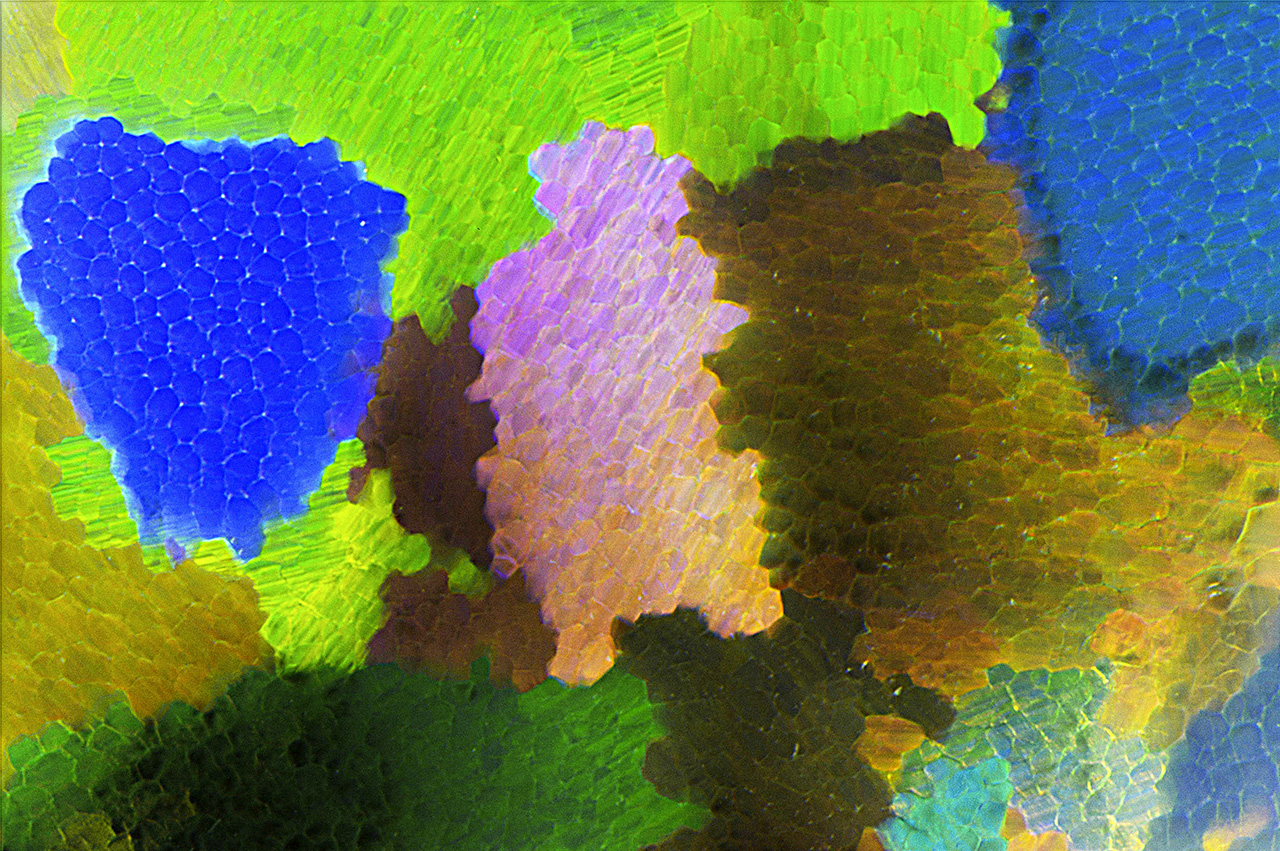

One of the more prominent opal imitations was introduced in the early 1970s by John Slocum of Rochester, Michigan. In this imitation, thin sheets of metal foil were embedded in glass to produce thin-film interference colors resembling “play-of-color” in natural opal. In 1972, Pierre Gilson began to manufacture a true synthetic opal (Gübelin and Koivula, 2005) that did not require polymer impregnation. Synthetic and imitation opals have been produced over the years by other manufacturers including Kyocera, Almaztechnocrystal, and Openallday Pty. Ltd, but the most recent development is an opal-like plastic manufactured by Kyocera and others in Japan (Renfro and Shigley, 2017). This new material is 80% plastic and 20% silica. It can be produced in large sizes, giving rise to industrial applications such as use in eyeglass frames and watches.

While the images in the accompanying wall chart are by no means comprehensive, they do represent a wide variety of the micro-features one might encounter in natural, treated, synthetic, and imitation opals.