Fabergé Cossack Figures Created from Russian Gemstones

ABSTRACT

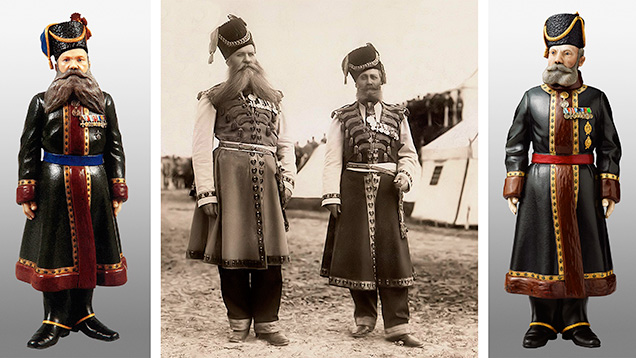

Between 1908 and 1916, the workshops of the Russian court jeweler Carl Fabergé created approximately 50 hardstone figures representing the Russian people, including peasants, merchants, noblemen, and soldiers. Made from gems and precious metals, they are as rare as the well-known Imperial Easter eggs. The last Romanov emperor, Nicholas II, owned 21 of these portrait figures, two of which depict the Cossack bodyguards of the Romanov empresses. This article examines the hardstone figures through known biographical details, archival photographs of the Chamber Cossacks Kudinov and Pustynnikov, an original production sketch, and an invoice from the Fabergé firm. It discusses the creation of the pieces from gemstones and minerals mined in Russia.

INTRODUCTION

To find a Fabergé piece lost in an attic for 79 years and sell it in less than 15 minutes for close to $6 million must be the ultimate thrill in auctioneering. The object in question was a carved hardstone replica of N.N. Pustynnikov, the personal bodyguard from 1894 to 1917 of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1872–1918). In a 2015 interview with the authors, Colin Stair of Stair Galleries described the rediscovery of the Fabergé figure in an attic in Rhinebeck, New York, and the October 2013 auction with one word: “Amazing!”

The story begins with the last Russian emperor, Nicholas II (b. 1868–1918), who was an avid collector of Fabergé hardstone carvings representing his subjects: peasants, merchants, noblemen, and soldiers. Records show that between 1908 and 1916 the Russian court jeweler Carl Fabergé (1846–1920) had commissions to create approximately 50 figures from various gem materials and precious metals (Adams 2014). These pieces are today as rare as the famous Imperial Easter eggs. Nicholas II owned 21 of them, including two with a special connection to the imperial family: a pair of Cossack1 bodyguards who had served the Romanovs for many years (figure 1).

Since the time of Nicholas II’s great-grandfather, Nicholas I, Russian emperors had assigned personal bodyguards to empresses and wives of heirs to the throne. Those appointed were Cossack noncommissioned officers from the emperor’s own escort or other elite guard units. Known as Chamber Cossacks, they served not as soldiers but as “court servants of the first category.” Their ceremonial dress, adapted from late 17th century Cossack and Russian attire, contrasted sharply with the Prussian-inspired livery of most other servants. As many as three Cossacks were assigned to an empress. They worked on a rotating basis, typically spending two weeks on duty and one week off. They were appointed for life and enjoyed privileges such as free lodging and health care. The Chamber Cossacks were mostly seen in public when an empress left her palace, occupying a seat of the royal carriage or automobile. They also accompanied her on trips outside of Russia.

The senior Chamber Cossack honored with a Fabergé figure is A.A. Kudinov, who guarded Nicholas II’s mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (1847–1928). The 7.5 in. (19 cm) Kudinov piece was the 18th hardstone figure Nicholas II purchased from Fabergé. It was displayed in the Pavlovsk State Museum Collection (near St. Petersburg) from 1925 until 1941, and again after 1956. The recently rediscovered figure of Chamber Cossack N.N. Pustynnikov, also 7.5 in. tall, was purchased at the 2013 Stair Galleries auction by the British firm Wartski, a leading Fabergé dealer. Explored in this article are known biographical details and archival photographs of Kudinov and Pustynnikov, an extant Fabergé production sketch, and the use of Russian gem materials and precious metals in the figures.

BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF THE CHAMBER COSSACKS

Andrei Alexeevich Kudinov (1852–1915; figures 2 and 3) was born in the Cossack village of Medveditsa Razdorskaya in western Russia. He started his military service in 1871 and became a noncommissioned officer in 1876. He served in the Danube Army during the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War and was later appointed orderly and bodyguard to the heir, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (later Alexander III). In December 1878, he was assigned to Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna, the wife of the future emperor; he stayed at this post when she became empress in 1881 and continued until his death. With his wife and three children, he lived at Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg (The State Hermitage Museum, 2014).

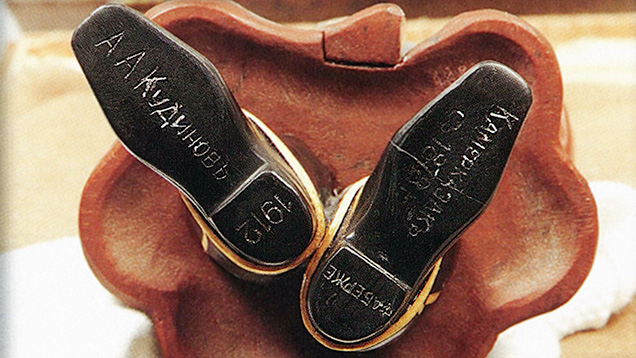

Kudinov’s service record is kept in the Russian State Historical Archives in St. Petersburg. His career is also represented in the Fabergé figure by the engravings on the soles of his boots (figure 4) as well as the badges and medals on his neck and chest (figure 5). Around his neck, the Kudinov figure wears two large Medals for Zeal, the top one in gold from Nicholas II (awarded in 1906 for 30 years of service as a noncommissioned officer) and the lower one in silver from Alexander III (1893).

Nikolai Nikolaevich Pustynnikov (1857– after 1918; figures 6 and 7) was originally from the city of Novocherkassk, northeast of the Black Sea. Pustynnikov started his military service in 1876; he had a talent for music and in 1877 joined the regimental band as a trumpeter. In 1878, he was sent to St. Petersburg to join the band of the Guards Combined Cossack Regiment. Pustynnikov became a noncommissioned officer in 1881, and from 1884 to 1894 he was a trumpet major of His Majesty’s Guards Cossack Regiment, even receiving a gold presentation watch from Alexander III for a solo performance. In December 1894, he was appointed by Nicholas II to guard Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. He served at Nicholas II’s 1896 coronation and lived along with his wife and nine children in the servants’ quarters at Tauride Palace and later at the Winter Palace (The State Hermitage Museum, 2014).

Pustynnikov’s service is also reflected on his figure’s boot engravings (figure 8), badges and medals (figure 9). Around his neck are two Medals for Zeal awarded by Nicholas II in 1902: the top one in gold on a ribbon of St. Stanislas and the silver medal below on a ribbon of St. Alexander Nevsky.

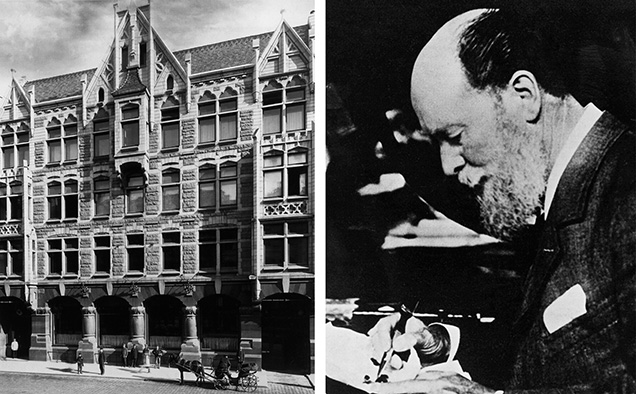

THE WORLD OF CARL FABERGÉ

In August 1842, Gustav Fabergé (1814–1893) established a small jewelry business in St. Petersburg (figure 10, left) that lasted until 1918, when it was closed forever by the Bolsheviks following the Russian Revolution (Lowes and McCanless, 2001). Gustav’s third son, Carl Fabergé, took over in 1872 (figure 10, right). With its amazing creations under his leadership, the firm was named Supplier to the Imperial Court in 1896. This began a long and fruitful relationship with the Romanovs. The firm supplied them with Easter eggs, presents for Christmases, birthdays, and name days, plus a variety of picture frames, presentation gifts, bell pushes, cigarette cases, cane handles, and hardstone animal and portrait figures. The House of Fabergé in St. Petersburg, along with its branches in Moscow (which specialized in silver), Kiev, Odessa, and a sales office in London from 1903 to 1917, catered to an elite clientele worldwide. Gems and minerals gathered across the Russian Empire were sent to the two main Fabergé production centers in St. Petersburg, with 500 employees, and Moscow, with 300 employees.

By 1908, the lapidary workshop, located in the courtyard of a three-story building at 44 English Avenue in St. Petersburg was equipped with 10 electric motors, 14 machines for processing stones, an emery wheel, and a kiln. At its peak, the workshop employed 30 expert craftsmen. By 1912–1914, the demand for hardstone animals as collectors’ items would prompt Fabergé to increase its workforce and outsource work to stonecutters in Ekaterinburg, a city on the eastern side of the Ural Mountains (Muntian, 2005). But it was the craftsmen in St. Petersburg who transformed Russian gems and minerals into a variety of hardstone sculptures, including the two Chamber Cossacks commissioned by Nicholas II.

RUSSIA’S MAJOR MINING LOCATIONS

Fabergé had the natural resources of the Russian Empire at its fingertips. From beautiful pink rhodonite mined in the Ural Mountains to black obsidian and red-brown sard from the Caucasus Mountains and Siberian nephrite in rich shades of green, they were able to access the most varied and colorful gemstones for the jeweler’s art. For centuries, Russia has also been a major source of precious metals such as gold, silver, and platinum.

Figure 11 shows the general locations of the gem and precious metal sources over the Russian Empire’s 6.6 million square miles, as well as the route used by the Trans-Siberian Railway to transport the mining yield.

Three large mountain ranges provided the majority of the stones for Fabergé. The Caucasus Mountains are made up of two parallel mountain ranges, the Greater and Lesser Caucasus, that extend from the northern shore of the Black Sea southeast to nearly the Caspian Sea. These mountains formed as a result of a tectonic collision between the Arabian and Eurasian plates. There is still volcanic activity, especially in the Lesser Caucasus, forming deposits of obsidian, a volcanic black glass used in stone carvings for its lustrous finish. Sard, calcite, garnet, amethyst, rutile, and quartzite are also found in the Caucasus.

| Chronology of the Two Chamber Cossack Figures |

| 1912: Both figures are created by Fabergé and purchased by Nicholas II. 1918: After the Russian Revolution, the emperor’s hardstone figures are traded by various dealers: Armand Hammer, Agathon Fabergé (second son of Carl Fabergé, 1876–1940), and Wartski, London. The Pustynnikov figure is brought to the United States for sale by Armand Hammer. 1925: The Kudinov figure goes on display at the Pavlovsk State Museum Collection until 1941. December 11, 1934: Hammer Galleries in New York sells the Pustynnikov figure for $2,250 to Mrs. George H. Davis of Manhattan and Rhinebeck, New York. 1956: The Kudinov figure goes back on display at the Pavlovsk State Museum. October 26, 2013: The Pustynnikov figure is offered for sale by the descendants of Betty Davis, the original American owner. The piece has remained in the family’s hands since 1934 and has not been exhibited for 79 years. It is auctioned at the Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York. |

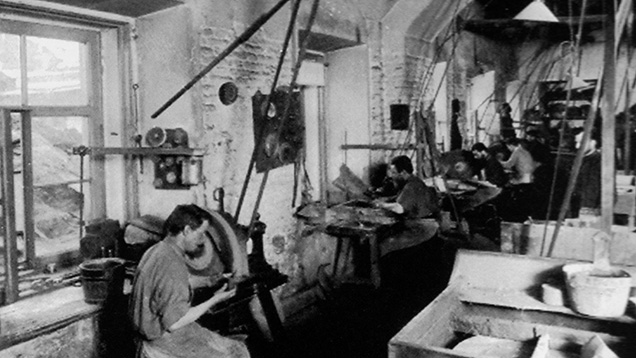

The Ural Mountains, which form part of the boundary between Europe and Asia, extend more than 1,550 miles (2,500 km) from the northern border of Kazakhstan to the Arctic coast. The word Ural is thought to be of Turkish origin, meaning “stone belt.” Russian mineralogist Ernst Karlovich Hofmann (1801–1871) explored this mountain range extensively beginning in 1828. Traveling thousands of miles, he collected gold, platinum, rutile, chrysoberyl, quartz, topaz, and other metals and minerals. The region became a virtual cornucopia of riches used in the thriving stone carving industry of Ekaterinburg. Malachite, amethyst, demantoid garnet, alexandrite, rhodonite, lapis lazuli, carnelian, sardonyx, and jasper mined with hand tools (figure 12) were carved into boxes, paperweights, and stone sculptures for a worldwide market.

The Altai Mountains and Siberia, with large diamond and nephrite deposits and vast resources of other gems and minerals, have supplied the jewelry trade for decades. Siberia makes up 77% of Russia’s territory, extending east from the Ural Mountains to the borders of Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan, and north to the Arctic Ocean and Bering Sea. On the southern border of Russia, the Altai Mountains are a source of aventurine quartz and gold. The Trans-Siberian Railway, constructed in stages from 1891 to 1916, linked the region to the rest of the Russian Empire and allowed greater access and use of these resources. Among colored gemstones, Siberian amethysts are known to be of the finest color. An imperial decree controlling the mining of Siberian green nephrite (highly prized for its rich color) increased that material’s value. Since the 18th century, the Altai Mountains, which reportedly get their name from the Mongolian and Turkic word for gold, and the many gold-producing river basins in Siberia have made Russia a major supplier of gold. The Amur River region alone produced 96 tons from 1902 to 1915 (Habashi, 2011). Russia’s important silver-producing regions are in the central and southern parts of the country. Major platinum deposits are in northern and eastern Siberia, near the Arctic Circle.

CREATING THE FABERGÉ CHAMBER COSSACKS

In 1912, Kudinov and Pustynnikov were asked to pose for Fabergé hardstone figures commissioned by Nicholas II. An existing watercolor production sketch of the Pustynnikov figure from Fabergé’s third and last senior workmaster, Henrik Wigström (active 1903–1917), is shown in figure 13. Preliminary sketches guided the selection of colors and the pose of the figure. Next, a wax model was made to scale and proportion. Once the model was completed, it was sent to either the Fabergé lapidary workshop or the independent workshop of Karl Wörffel (figure 14), to be duplicated in polychrome gemstones carefully selected and matched for color and texture. Wörffel had one of the largest and finest stone cutting and bronze casting factories in St. Petersburg until his shop was acquired by Fabergé in 1915. His workshops served not only the Imperial Court but also clients in Germany, England, France, Belgium, and the United States. He supplied the House of Fabergé on a regular basis with hardstone animals, figures, flowers, and objets d’art. Wörffel’s cutters also held a monopoly over Russia’s nephrite supply, and had experience working with stones from the Caucasus, Ural, and Altai mountain ranges (Lowes and McCanless, 2001).

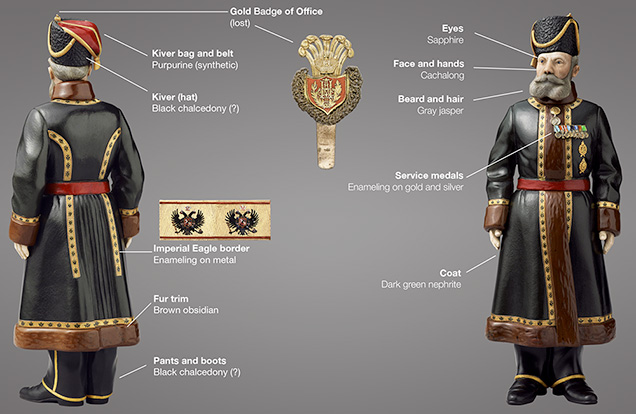

Each stone sent to the lapidary was cut to very precise measurements using both a cutting wheel and hand tools. Once the form and textures were perfectly carved, each piece of stone was brought to a smooth, lustrous finish on a polishing wheel. The pieces were assembled one at a time and joined with animal hide glue, before the final step of applying the gold and silver medals and trim. The variety of stones used in Pustynnikov’s figure are detailed, from the most prominent to the smallest features, in figure 15 and in the text below.

Coat. The wool coat is carved from dark green nephrite. The realistic folds in the sleeves and the natural drape create a sense of movement and life. Independent Russian researcher Valentin Skurlov (2015) found that regardless of the variety of materials available, Fabergé’s artisans preferred nephrite. In fact, the House of Fabergé in St. Petersburg was given special permission to keep four tons of the finest-quality nephrite, guaranteeing the craftsman always had ready access to this popular stone. The toughest of all natural stones, nephrite is opaque or translucent when cut very thin. The winter coat was trimmed with otter fur and a Romanov Imperial Eagle border. Fabergé replicated the fur with brown obsidian, and the double-headed eagle pattern of the border was fired onto metal strips and then applied as borders to the nephrite.

Pants, Boots, and Kiver (Hat). Without instruments to test gemological properties, one has to rely on visual clues. The items with a black fur texture (pants, boots, and kiver) are most likely chalcedony. Alternate black stones used in these figures could be jasper, onyx, jet, jade, or obsidian. The pants are trimmed in gold.

Kiver Bag and Belt. Hanging from the top right of each Cossack guard’s kiver was a colored bag. The color of this bag and the belt worn around the waist corresponded to the empress served: blue lapis lazuli for Maria Feodorovna (Kudinov, see figures 16 and 17, left and center) and red purpurine for Alexandra Feodorovna (Pustynnikov; again, see figure 15). Purpurine, a deep crimson vitreous material brought about by the crystallization of lead chromate in a glass matrix, is the only synthetic material on either Cossack figure. Fabergé made great use of this material, especially in his animal figures.

Badges and Service Medals. Each Cossack’s kiver features gold braid trimmings and a tassel of bullion fringe. Attached to the top left of the kiver is a Gold Badge of Office (seen in detail in figure 17, right) in the shape of a crowned escutcheon, with a gold monogram of the empress. The escutcheon is topped by ostrich feathers and surrounded by bullion braid to which removable rackets were suspended for ceremonial dress (The State Hermitage Museum, 2014). Pustynnikov’s badge is missing from the Fabergé hardstone figure.

Service medals on the chest of the Fabergé figures are enameled, a process in which powdered glass is mixed with metal oxides fired at 600°–800°C (1300°F) to create a hard glossy finish in a variety of colors (figure 18). The delicately enameled medals applied to the nephrite coats of Kudinov and Pustynnikov are extremely small, yet remarkable for their accuracy (D. Brière, pers. comm., 2016).

Face and Hands. These features are carved from cachalong, a type of milky white to pale pink opal. It is easily carved, allowing the artist to give the face greater detail and personality and a more lifelike expression. Pustynnikov’s attentive stare is in keeping with his duties as an imperial bodyguard. Cachalong is often mistaken for agate or chalcedony. Frequently misidentified in the Fabergé literature as a synthetic material, it has been used predominantly since 1913. Prior to that, the harder stone of aventurine was generally used to carve faces and hands in Fabergé’s hardstone figures.

Beard and Hair. The two Cossack figures are similar but readily distinguished by their belt colors and by Kudinov’s split beard. The beard and hair are made of gray jasper carefully detailed with a lifelike texture. Dark gray Kalgan jasper was used for Kudinov and gray jasper for Pustynnikov.

Eyes. The Cossacks’ eyes glow with cabochon-cut blue sapphires from the southern Ural Mountains. Sapphires from this source were used in all but two of Fabergé’s hardstone figures. When used en cabochon, cut and polished to a convex shape, the sapphire replicates the natural shape and eye color.

CONCLUSIONS

On an existing 1912 invoice from the House of Fabergé (figure 19) for the Kudinov figure, Nicholas II—not the Imperial Cabinet—is billed 2,300 rubles. It has been suggested the two Chamber Cossacks were by far the most expensive of the hardstone figures made. The cost of the original Kudinov, based on Benko (2015), equates to approximately $1,185 in 1912, and $28,200 in 2013. The Pustynnikov figure sold for nearly $6 million in 2013.

Fabergé scholar Alexander von Solodkoff (1988) noted, “The different parts were assembled so perfectly that the joints are invisible to the naked eye and frequently cannot even be detected with a needle.” More than 20 of these hardstone figures have been sold through Wartski Jewelers in London since the 1920s. In the words of the late A. Kenneth Snowman, Fabergé historian and proprietor of Wartski, Carl Fabergé had the

unerring instinct for the right material, the meticulous treatment of detail, the vigorous sense of movement, and perhaps, above all, the obvious affection for and sympathy with the subject...Painstakingly carved pieces of stone of a suitable color and texture, each playing their appointed part, were carefully- and invisibly-fitted together. (Snowman, 1953, p. 65)

It is this attention to detail and precision craftsmanship for which Fabergé is famous. Even the most whimsical of his creations were designed with great care. His employees took pride in their work and were paid the highest wages in the industry. This attracted the best of the best to Fabergé. With access to the finest artists and the great gem and mineral wealth of Russia, Carl Fabergé built a lasting legacy of elegant perfection.