Repaired Grandidierite

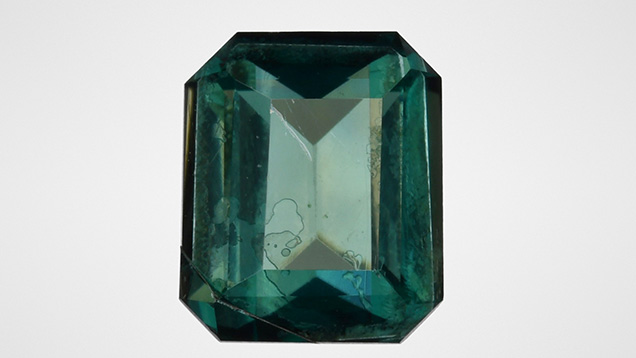

Recently the Carlsbad laboratory received for identification services a transparent bluish green stone weighing 1.43 ct and measuring 7.47 × 6.31 × 4.06 mm (figure 1). Standard gemological testing revealed a refractive index of 1.58–1.62 on both the crown and pavilion, suggesting that both the crown and pavilion were grandidierite. This was confirmed using FTIR and Raman spectroscopy. Microscopic examination showed a very large fracture that broke continuously around the entire stone. Closer inspection revealed that the fracture was filled (figure 2), and this filling was holding the stone together, indicating that the stone was likely broken into two pieces and then repaired with a resin or glue.

Grandidierite is a very rare mineral, and transparent gem-quality material was not found in the market until 2015 (Winter 2015 Gem News International, pp. 449–450). Named after French naturalist Alfred Grandidier (1836–1912), grandidierite was first discovered in 1902 at the cliffs of Andrahomana on the southern coast of Madagascar (D. Bruyere et al., “A new deposit of gem-quality grandidierite in Madagascar,” Fall 2016 G&G, pp. 266–275). This is the first repaired grandidierite GIA has seen to date.