History of Emerald Mining in the Habachtal Deposit of Austria, Part II

ABSTRACT

Published information about the history of the Habachtal emerald mine in the era between World War I and World War II is limited and superficial. Subsequent to the departure of Emerald Mines Limited, the English company that had owned the property since 1896, the Habachtal mine was owned or controlled by Austrian, Swiss, Italian, or German companies or citizens. The names of various companies and individuals who were actively mining for some time in the Habach Valley are mentioned in numerous papers, books, or newspapers. The relationships between them and the property owners mentioned in files of the Mittersill land registry office are frequently unknown and the reasons for numerous transitions of ownership, followed by changes of the mining entities that operated the deposit, are not clearly seen. Using a wide selection of materials from Austrian and German archives, largely unpublished, the author seeks to trace the history of the Habachtal mine through this period and to fill the gaps left by existing publications. Activities and events after 1945 and the present situation are also briefly described.

In the first part of this article, it has been shown that no regular mining occurred in the Habach Valley up until the end of the eighteenth century. After the secondary deposit in Habachtal was described in 1797, emeralds were collected in the valley, and regular mining commenced in the early 1860s after the discovery of the primary deposit. For several decades, from about 1865 to 1895, only minor activities took place in the primary and secondary parts of the deposit. In contrast, major activities with up to 30 miners are seen under English guidance and ownership by Emerald Mines Limited, from 1896 to 1913. Thereafter, the ownership reverted to three Austrian citizens: Alois Kaserer, Johann Blaikner, and Peter Meilinger, all landowners and farmers in the area. However, the outbreak of World War I prevented them from starting any regular mining on a larger scale and prompted them to sell the property. This is the starting point for part two of the Habachtal investigation.

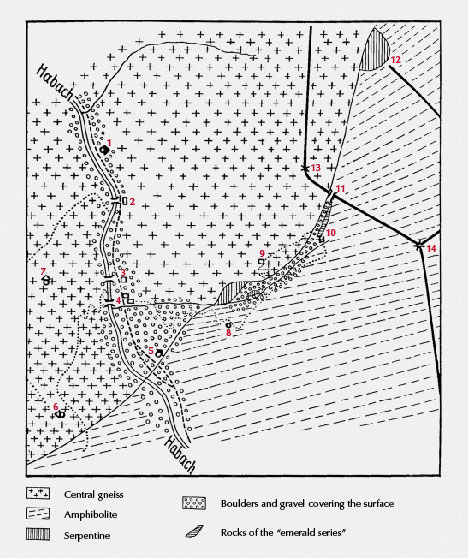

The first half of the twentieth century brought numerous transitions in ownership and various mining activities (see figure 1) that also have, until now, not been described in detail with regard to the unpublished original documents preserved mainly in Austrian and German archives. In part two, the focus is laid upon this era. It will illustrate the problems that occurred in emerald mining, the individuals involved, and their success or failure in emerald recovery in Austria.

MINING HISTORY OF THE HABACHTAL EMERALDS (1916–1939)

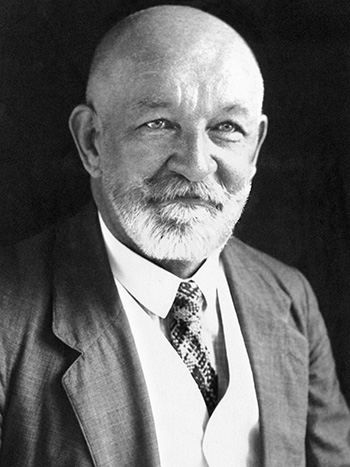

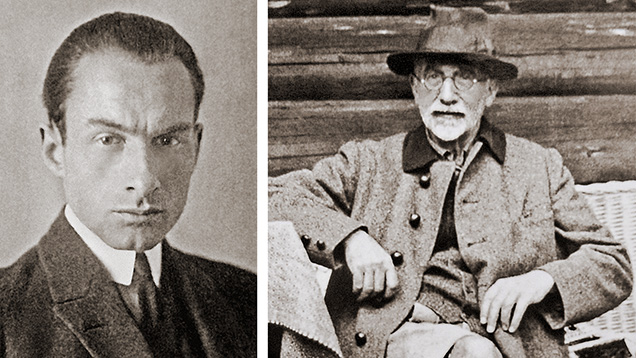

Property Under Anton Hager and Peter Staudt (1916–1927). In October 1916, landowners Kaserer, Blaikner, and Meilinger resold the property for 15,000 Kronen (approximately US$1,900 at the time) to Anton Hager (figure 2), an Austrian citizen then residing in Traunstein, Germany.1 Prior to that transaction, Hager had already applied for several exploration permits in the area.2 Circa 1917, an anonymous memorandum was written, likely by Hager, describing the history of the Habachtal emerald mine and its current condition.3 Certain comments hinted at a possible intent for future emerald mining, and it was noted that the adit to the D gallery was still blocked by rocks and needed to be reopened.

In July 1918, Hager began efforts to restore the property with five laborers, and that work continued in the following years.4 Additional exploration permits were sought by Hager in 1918, and he also applied that same year for permits for talc production near the emerald deposit.5 During that era, talc was mined for various applications such as cosmetics, pharmaceutical products, glass, specialized papers, leather, textiles, and soap.6 Mining engineer Heinrich Stuchlik (figure 3) of Traunstein provided Hager with estimates for a supply of 200 wagons per year with a reserve for 100 years, even speculating as to whether the talc occurrence might extend over the mountain ridge to allow economic mining for talc in the adjacent Hollersbach Valley as well.7

Beginning in August 1918, Hager searched for a chemist and/or a partner to invest alongside him in the Habachtal venture.8 A figure of 800,000 Kronen was proposed as the amount necessary for mining and transport of the rough talc downhill.9 Finding no takers, in September 1920 Hager sold a one-half interest in the property to his half-brother Peter Staudt (figure 4) from Traunstein for 31,000 Kronen10 (approximately US$100 at the time). An entity under the name Talk- und Edelsteinbergwerk Habachthal (Talc and Gemstone Mine Habachthal) was founded in 1920 for purposes of the venture.11 Hager and Staudt resumed emerald mining that same year12 and continued to consider activities in the area not related to gemstones, such as the extraction of talc and even asbestos from the schistose rocks.13

1Notarized contract between Alois Kaserer/Johann Blaikner/Peter Meilinger and Anton Hager, October 26, 1916, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry January 5, 1917, Mittersill land registry office. Anton Hager (1872–1940) was a timber merchant involved in his stepfather’s company at Traunstein, originally hailing from the area of Zell am See in the Pinzgau and then living in Traunstein from 1900 to 1926. He moved in 1926 to the community of Gnigl (which in 1935 became part of Salzburg). Franz Haselbeck, Traunstein City Archive, pers. comm., 2020; Brigitte Leitermann, granddaughter of Peter Staudt, pers. comm., 2020.

2File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

3Anonymous, Das Smaragd-Bergwerk im Habachthale, Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg, circa 1917, 6 pp. The exposé was prepared on stationery from the desk of “Carl Staudt, Holzhandlung, Traunstein” and likely written by Hager.

4File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang.

5File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

6Wenzel, 1921.

7Letters from Heinrich Stuchlik to Anton Hager (dated December 5, 1918, August 7, 1919, and August 12, 1921), Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg. Stuchlik was born in the Austrian part of Silesia near Troppau, now in the Czech Republic, and studied at the Imperial and Royal School of Mining in Leoben. Early in life, Stuchlik focused on coal, publishing in 1887 about the deposit in his home village of Schönstein. In the late 1880s, he moved to Bavaria and worked at the coal deposit in the Peissenberg area, serving from 1897 to 1905 as head of the mining administration. From 1905 to 1912, he was the administrator for the saltworks of Traunstein. During World War I, Stuchlik was involved in mining in Romania. See Haselbeck, 2019.

8Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 48, No. 179, August 7, 1918, p. 5.

9Letter from unknown sender (signature illegible) to Anton Hager, August 19, 1919, Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg.

10Notarized contract between Anton Hager and Peter Staudt, September 27, 1920, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry December 4, 1920, Mittersill land registry office. Peter Staudt (1883–1948) was a timber merchant in Traunstein, leading a large company with up to 20 workers that had been founded by his father Carl Staudt in 1897 and remained in existence until 1928. Franz Haselbeck, Traunstein City Archive, pers. comm., 2020; Brigitte Leitermann, granddaughter of Peter Staudt, pers. comm., 2020.

11File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang; Compass, Industrielles Jahrbuch – Österreich, Vol. 61, 1928, p. 388.

12File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 58, No. 240, October 18, 1928, p. 7; Grundmann, 1979; Lausecker, 1986; Lewandowski, 1997; Düllmann, 2009.

13Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 54, No. 174, July 31, 1924, p. 7.

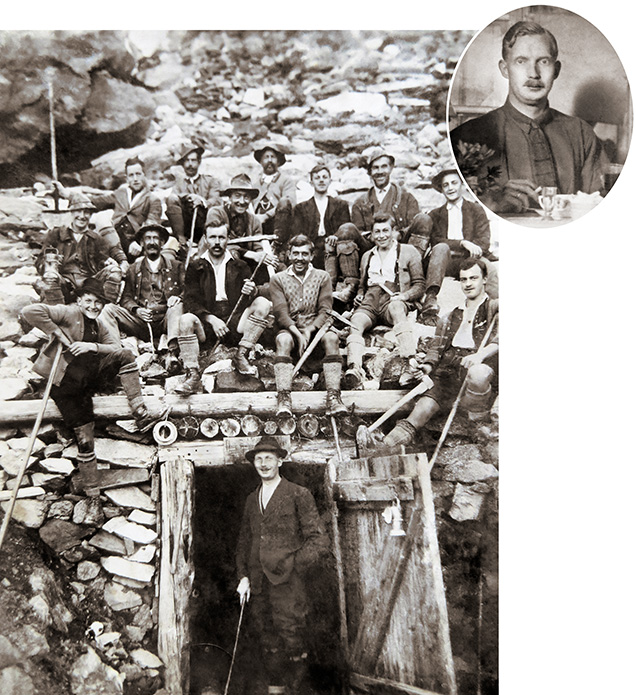

Investigation of mining prospects proceeded in 1920 and 1921. Inspection reports of the area were prepared by engineer Ludwig Autzinger of the firm Abihag in Linz and Graz14 (who also published his results in 1922) and by mine foreman Johann Hanisch (figure 5),15 and chemical analyses of talc were commissioned from laboratories in Salzburg, Vienna, and Munich. Besides noting that the mine was well maintained and all entries to the four galleries were accessible, Autzinger focused on potential production.16 For talc, he calculated 400 railway wagons (with 10,000 kg per wagon) per year by open-pit mining, with reserves for 200 years. For emerald, Autzinger used a wildly optimistic yield reported to him for the period of the English ownership of 5 kg (25,000 carats) of clean emeralds per week and projected similar totals. (Note that this figure was never reached even during one complete season, and such a weekly yield would have made selling the mine financially irrational.) Hanisch’s report centered on the mine’s condition and recent efforts to prepare it for operation, advising that the previously decrepit galleries had been renovated in 1920 and that safety measures had been undertaken.17 Also in 1920, H. Obpacher of the Mineralogical-Geological Laboratory at the Munich Technical University examined the talc-bearing rocks. Petrographic thin sections were prepared to determine the mineral assemblage, and methods for processing and cleaning the talc and asbestos were evaluated.18

Based on the production figures provided by Autzinger, a detailed business plan was developed by K.E. Moldenhauer from the Institute for Chemical Technology at the Munich Technical University and presented to Hager and Staudt in December 1920.19 The cost for open-pit mining of talc, underground mining of emeralds, and transportation of the ore downhill was estimated, as was the outlay for recommended supporting facilities. An electric power plant was to be built, along with facilities for separating emeralds from host rock, grinding and sieving talc ore, magnetic separation of iron-bearing components, and drying, weighing, packing, and transporting the refined talc powder to the railway station. The emerald and talc business lines were said to require a combined investment in the range of 8,500,000 German marks (approximately US$150,000 at the time). Nonetheless, the enterprise was expected to be profitable based on the unrealistic estimated 5 kg per week yield and value of 250,000 marks per kilogram of emerald rough, amounting to weekly revenue of 1,250,000 marks (approximately US$22,000) from the emerald line alone.

In 1921, Hager and Staudt applied for and received the requisite working permits for the mine, and an application for permission to install the plant and transport facilities for the talc production was filed by Hager the same year. Operations on site in 1921 were supervised by Austrian mining engineer Josef Gerscha (1864–1941, figure 6), who was forced to deal with the lack of proper maintenance of the galleries for more than a decade following the activities of the English proprietors.20

14Ludwig Autzinger (1890–1964) studied civil engineering at the Technical University of Vienna from 1908 to 1915 and served as an assistant at the school in 1917. He subsequently worked in various industrial capacities, including director of a fertilizer factory. In 1939 he emigrated to the United States.

15Johann Hanisch (b. 1885) was a foreman at the Mitterberg copper mine (owned by Mitterberger Kupfer-Aktiengesellschaft) near Mühlbach at the Höchkönig from 1916 to 1924. The deposit had been known since the Bronze Age.

16Autzinger L., Über das Talk- und Smaragdbergwerk in Habach, Post Bramberg im Pinzgau, July 1920, 4 pp. + map, Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg; see also Autzinger, 1922.

17Hanisch J., Bericht über den Smaragdbergbau oberhalb der Söllalpe im Habachtal, January 20, 1921, 2 pp., Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg.

18Obpacher H., Begutachtung von Gesteins- und Mineralproben (vorgelegt von Dipl. Ing. Moldenhauer) aus dem Talk-Asbest- und Smaragdvorkommen im Habachtal am Grossvenediger, December 18, 1920, 9 pp., Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg.

19Moldenhauer K.E., Das Talkum-, Asbest- und Smaragd-Vorkommen im Habachtal (Oberpinzgau) und seine Verwertung, December 1920, 36 pp, Archive of the Municipality of Bramberg.

20File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Schiffner, 1940; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang.

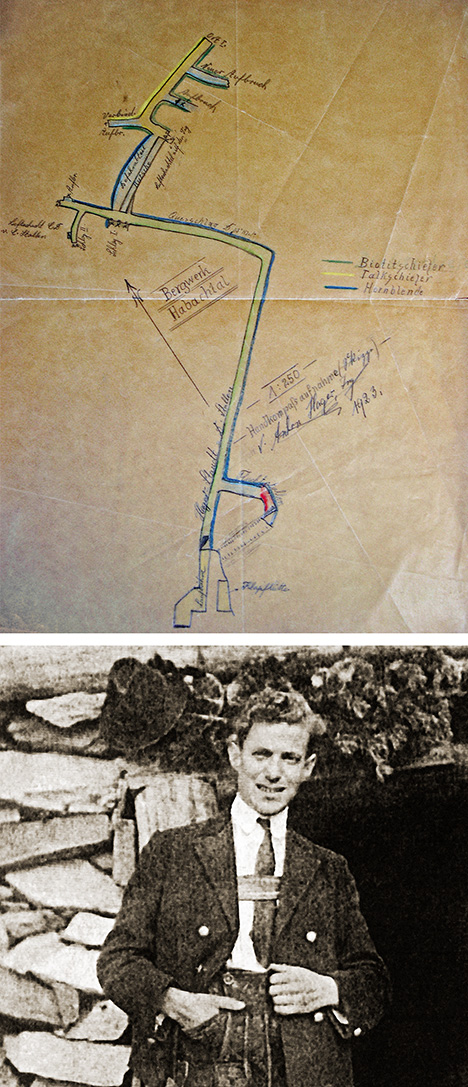

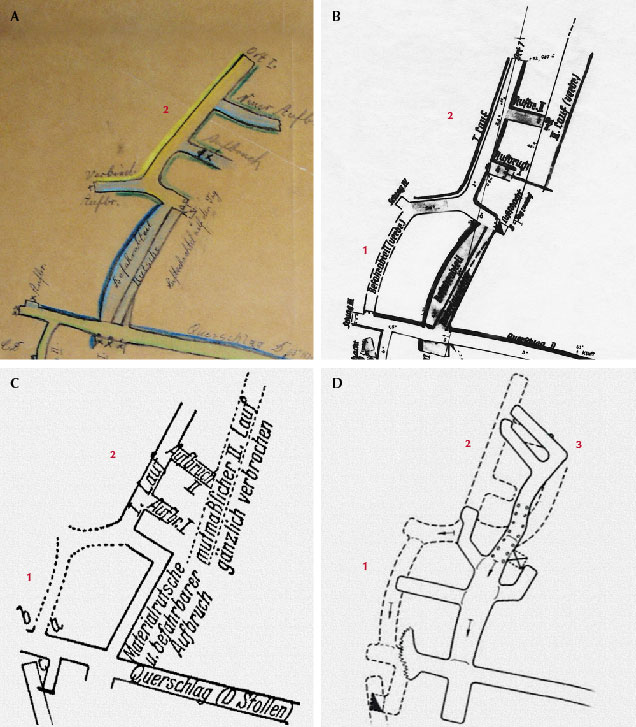

While talc production seems never to have advanced beyond preliminary or experimental stages, and the intended facilities were never constructed, emerald mining was undertaken on a larger scale.21 An unknown number of workers was employed in the enterprise, and Anton Hager Jr. (figure 7), son of the owner, joined in the effort.22 Between 1923 and 1926, extensions were added to the extremities of the D gallery tunnel system (figures 7 and 8) and German Dr. Max Brennekam (figure 9) took over responsibility as mining engineer for operations.23 The record indicates that Hager and Staudt experienced solid emerald production in some years but that marketing and sales were ineffective.24 Meanwhile, in February 1924 an option to purchase the property was recorded with the Mittersill land registry by Hager and Staudt in favor of Adolf Eichmann, an investor and merchant of electrical devices from Linz, but it terminated the same year without exercise.25

21See Fritz, 1972.

22Anton Hager Jr. (1902–1980) was born in in Traunstein. He later studied mechanical engineering at the engineering school in Mittweida, Saxony, from 1921 to 1923.

23Dr. Max Brennekam (1870–1954) studied at the universities of Tübingen, Halle, and Greifswald and wrote a dissertation on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant (1895). In the following years, he worked as a schoolteacher in the Berlin region. After World War I, Brennekam shifted his focus to mining, spending a period from 1921 to 1928 in Austria. Together with his son Otto Brennekam (1899–1960), he served on the board of directors of the firm Kohle und Erz Aktiengesellschaft, which was founded in 1923 in Berlin and operated several gold mines in Austria. The 1940s found Brennekam as the owner of a feldspar mining company in Tirschenreuth, Bavaria. Montanistische Rundschau, Vol. 15, No. 22, 1923, p. 525; letter from K. Martius to W. von Seidlitz, June 21, 1938, Lagerstättenarchiv Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien; Eberl, 1972; Beate Heinrich, Archive of the Municipality of Tirschenreuth, pers. comm., 2020.

24Eberl, 1972.

25Option declaration given by Anton Hager/Peter Staudt in favor of Adolf Eichmann, February 24, 1924, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Grundmann, 1979.

Conflicts Over Interests in the Property (1927–1934). The property was eventually sold in October 1927, and ownership transferred along with several exploration permits held by Hager to the Swiss firm Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, located in Chur.26 This company had been registered in October 1927, with a stated capital of 100,000 Swiss francs (approximately US$19,000 at the time) and an initial board of directors consisting of Alfred Mannesmann (president) and Hermann Hoesch, both German industrialists; Hans Nipkow (vice president), Emil Frey, Bartholome Jeger, and Florian Prader (figure 10),27 all Swiss engineers or bankers; Conde de Santa Maria de la Sisla, a Spanish citizen and member of parliament representing Madrid; and Christian Buol, a lawyer from Zurich. A German banker named Justus H. Vogeler replaced Buol in 1929.28 A local office was set up in the Senningerbräu, an inn in Bramberg.29 The purchase price was 66,000 Swiss francs, to be paid in two equal installments by January 1 and May 1, 1928, respectively,30 and liens were recorded against the property to ensure full payment.

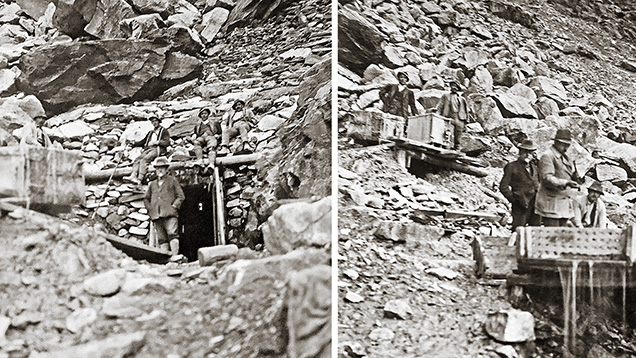

After the sale, mining resumed for approximately four weeks in the name of the new owner. Brennekam and Anton Hager Jr. stayed on, providing operational guidance for a team of eight miners.31 The emerald-bearing rocks were hauled in containers from the mine down to the valley in Bramberg for washing and crystal separation, the same procedure that had been utilized by Hager and Staudt for some time.32

Such efforts notwithstanding, regulatory and financial problems quickly intervened. Brennekam, serving as local representative for the mine owner, was directed to apply for a working permit for the Swiss Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, but he was unable to do so in the absence of consent from Switzerland, which was not forthcoming over several months. Brennekam left Bramberg and moved back to Berlin in June 1928.33

The company also failed to pay the second installment of the purchase price, leading Hager and Staudt to initiate foreclosure proceedings.34 The property was valued at 67,000 Austrian shillings, and the lowest acceptable purchase price was deemed to be 44,354 shillings (equivalent to the unpaid 33,000 Swiss francs).35 The auction scheduled for December 1, 1928, was averted, however, when Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau was able to obtain a loan of 50,000 reichsmark (equivalent to about US$11,900 at the time) on November 6 from Hans (Johann) Streubert, a mine owner and entrepreneur from Munich who also held interests in the neighboring Hollersbach Valley.36

Hager and Staudt were paid the remaining purchase price, and their liens against the property were released on November 9, 1928,37 while a new lien in favor of Streubert was recorded at the Habachtal emerald mine file of the Mittersill land registry office. Considering all the information available, Staudt had lost a substantial amount of money operating the Habachtal mine.38 Approximately two weeks later, on November 21, 1928, Streubert transferred his interest in the three-year loan in equal parts to Max Gaab (figure 11) and Meta Geist (figure 12).39

26Notarized contract between Anton Hager/Peter Staudt and Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, October 13, 1927, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry November 30, 1927, Mittersill land registry office; Montanistische Rundschau, Vol. 20, No. 9, 1928, p. 278.

27Florian Prader (1883–1946), a Swiss engineer from Zurich, owned several construction companies engaged in the building of railways, bridges, and power plants. Schweizerische Bauzeitung, Vol. 127, No. 12, March 23, 1946, pp. 148–149.

28Schweizerisches Handelsamtblatt, Vol. 45, No. 249, October 24, 1927, p. 1874; Vol. 47, No. 257, November 2, 1929, p. 218.

29Lausecker, 1986.

30Notarized contract between Anton Hager/Peter Staudt and Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, October 13, 1927, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry November 30, 1927, Mittersill land registry office.

31File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

32Ibid. See also Leitmeier, 1929/1930 (recounting a presentation given in March 1929 but adding observations from summer 1929 at the locality prior to final publication in 1930).

33File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

34Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 58, No. 240, October 18, 1928, p. 7; Vol. 58, No. 243, October 22, 1928, p. 8; Vol. 58, No. 244, October 23, 1928, p. 8.

35Reichspost, Vol. 35, No. 293, October 20, 1928, p. 7; Linzer Volksblatt, Vol. 60, No. 246, October 23, 1928, p. 9.

36Notarized contract between Hans Streubert and Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, November 6, 1928, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; see also Salzburger Chronik, Vol. 64, No. 275, November 30, 1928, p. 4; Reichspost, Vol. 35, No. 335, December 2, 1928, p. 7. Hans (Johann) Streubert (1866–1941) was born in Regenstauf, near Regensburg, Bavaria. He later resided in Munich and was active in mining operations at various localities in Austria. Between 1925 and 1929, he was one of the owners of the company Hollersbacher Zink- und Bleibergwerke. Grazer Volksblatt, Vol. 47, No. 69, February 21, 1914, p. 6; Montanistische Rundschau, Vol. 11, No. 6, 1919, p. 182; Vol. 15, No. 7, 1923, p. 115; Vol. 15, No. 16, 1923, p. 352; Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 55, No. 295, December 30, 1925, p. 7; Compass, Industrielles Jahrbuch - Österreich, Vol. 60, 1927, p. 410; Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 58, No. 186, August 14, 1928, p. 9.

37Notarized contract between Anton Hager/Peter Staudt and Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, November 9, 1928, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

38Peter Staudt thereafter closed his timber company in Traunstein in December 1928 and subsequently worked for the administration of the city of Traunstein. Company registration file, entry December 6, 1928, Archive of the City of Traunstein (Stadtarchiv Traunstein); Brigitte Leitermann, granddaughter of Peter Staudt, pers. comm., 2020.

39Notarized contract between Hans Streubert and Max Gaab/Meta Geist, November 21, 1928, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State. Max Gaab (1866–1953) was a lawyer from Munich. Meta Geist (1879–1966), residing in Munich and Fischbachau, Bavaria, was the daughter of food and coffee merchant Adolph Brougier and the widow of Theodor Geist, owner of Geist & Breuninger, a grain wholesaler in Munich. Gaab’s private apartment and the office of his law firm, both in Munich, were destroyed during World War II, leaving no documentation regarding events before 1945. Ingrid von Klitzing, granddaughter of Max Gaab, pers. comm., 2020.

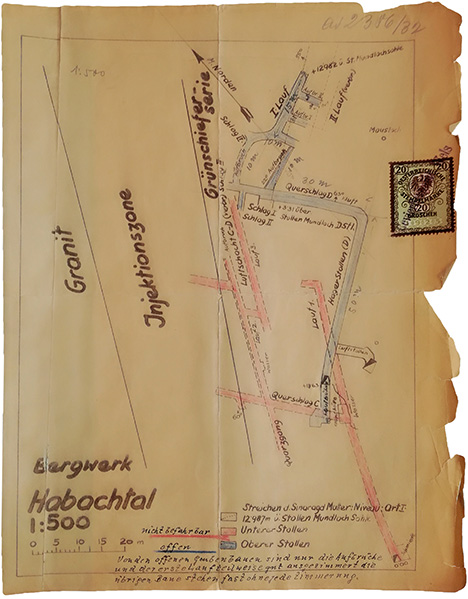

In December 1928, Smaragd-Bergbau Habachtal GmbH was founded in Mittersill to serve as the Austrian operating entity for the Swiss owner. Streubert, working from Munich, led the new firm.40 However, no regular mining took place from 1928 through the remaining period of Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau’s ownership.41 Instead, only limited exploration, maintenance of the tunnels, and trial mining ensued.42 In June 1929, Gaab loaned a further 5,000 reichsmark (equivalent to about US$1,900 at the time) to Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau,43 and mining expert Wilhem Müller was hired for trial mining and evaluation, which he did that month with seven workers.44 On the basis of 1,800 emeralds totaling 3,600 carats recovered during his time on site, with 2% of the crystals (72 carats) of facet quality, Müller compiled a report calculating annual income of 61,500 reichsmark, enough for profitability. He also prepared a map of the different galleries (figure 13) and offered detailed suggestions for how to target exploration for emerald-bearing schist in the C and D galleries.45 After his departure, exploration was led by E. Klein, who even then continued to communicate with Müller for counsel and expertise.46

40Although Hans Streubert worked from a Munich office, the company was registered only in Austria and not in Germany.

41File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Leitmeier, 1929/1930.

42Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 58, No. 294, December 24, 1928, p. 9; File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Letter from E. Klein to W. Müller, August 1, 1929, File “Beryllium,” Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt, Vienna.

43Notarized contract between Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau and Max Gaab, June 4, 1929, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

44Wilhelm Müller (born 1885) was educated at the mining school in Diedenhofen (now Thionville), Lorraine. He worked in the mining field in Lorraine and elsewhere and was involved in diamond recovery in the German colony of South-West Africa (now Namibia) before World War I. From 1920 to 1930, he was a manager of the Kappel/Schauinsland lead-zinc mine near Freiburg in southwest Germany, which had a staff of more than 200 miners. Müller lived in the Freiburg area during the 1950s. File “Akten des Bergmeisters Erzbergwerke Schauinsland,” 1920, Landesbergdirektion Freiburg; http://www.freiburg-postkolonial.de/Seiten/personen.htm; Heiko Wegmann, pers. comm., 2020; Helge Steen, pers. comm., 2020; B. Steiber, pers. comm., 2020.

45Müller, W., Smaragdvorkommen Habachtal – Salzburg, June 1929, 7 pp., File “Beryllium,” Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien; Letter from W. Müller to A. Cissarz, December 25, 1939, Lagerstättenarchiv Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien; Müller, W., Smaragd – Beryll – Vorkommen Habachtal, March 26, 1940, 2 pp., Lagerstättenarchiv Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang.

46Letter from E. Klein to W. Müller, August 1, 1929, File “Beryllium,” Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien.

In 1930, the Habachtal mine apparently became caught up in yet another financial scandal. A purported company under the name Deutsch-Österreichische Edelsteinbergwerks Gesellschaft was allegedly established in Munich to collect capital and issue shares in support of the “owner” of the mine, which was incorrectly referred to as the operating entity Smaragd-Bergbau Habachtal GmbH.47 Both a memorandum and a related business plan were prepared in service of those aims.48 The anonymous memorandum listed a board consisting of four directors of the Swiss parent company—namely Hoesch, Buol, Vogeler, and Conde de Santa Maria de la Sisla—as well as three German citizens (Friedrich Ritter von Heinzelmann, Heinrich Paxmann, and Friedrich Graf Larisch). The business plan offered a glowing picture of the mine’s potential and commercial relevance.

Emphasizing that the mines in Colombia were closed and those in the Urals completely exploited, the business plan considered the possibility of economic production not only of gem-quality emeralds but also beryllium-bearing minerals and talc. The plan cited earlier reports by mining engineer Emil Sporn from 1928,49 by Stuchlik also from 1928, and by Müller from 1929, somehow arriving at a property value of 684,000 reichsmark (or approximately US$163,000 at the time), an emerald yield of 60,000 carats in 1930, and a profit of 267,000 reichsmark in 1932, despite the obvious disparity with the more realistic figures tabulated by Müller.

Whether these missives had any impact on the investors targeted is unknown, but an examination by the Munich Chamber of Commerce in June 1930 revealed that no such company was legally registered there.50 It was later suggested that the alleged entity was linked to several individuals involved in other mining swindles in Germany who were sentenced to prison in 1932.51

Subterfuges aside, the actual mine owner Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau spent much of the 1930s enmeshed in a web of litigation and administrative proceedings, one in Switzerland and several in Austria. The opening salvo occurred when both Gaab and Geist, as creditors, filed separate lawsuits in Austria against the company for nonpayment of debts and interest.52 Those were apparently resolved through loans extended to the company by board member Prader and a Munich bank, which also resulted in further lien encumbrances against the property.53 This offered minimal respite, however, because a Swiss bankruptcy proceeding was opened in October 1931 but was then terminated three days later, without dissolution of the company, on account of a lack of any assets of value in Switzerland for distribution.54

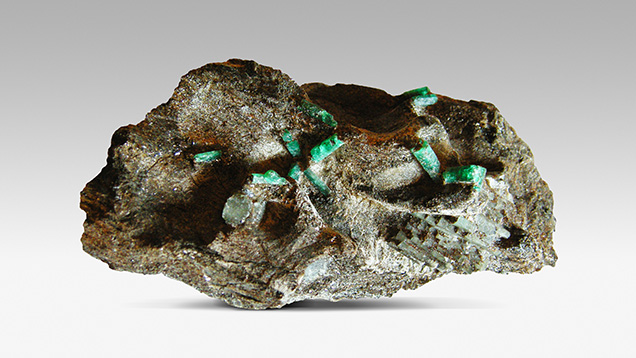

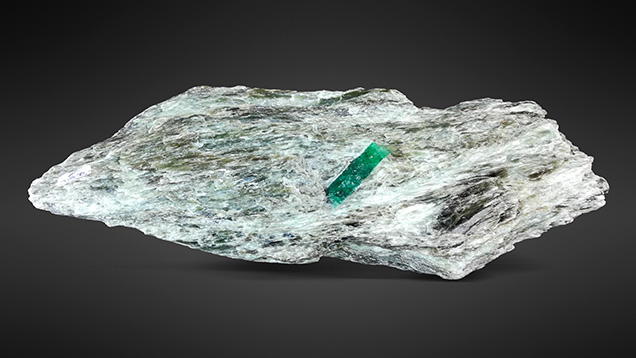

Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau remained the owner of the mine, and ensuing controversies shifted to Austria. The early years of the decade saw in particular several different groups of associates seeking to establish or pursue interests in the property (see table 1).55 Beginning in the 1930s, exploration permits were registered for the Habachtal area by Munich mining engineer Julius Burger56 in the name of Christian Schad (figure 14, left) and as directed by his father, Dr. Carl Schad (figure 14, right).57 Existing permits held by others were also purchased by and transferred to Christian Schad. At that time, technical progress had developed several lucrative applications for beryllium ore and metal (e.g., for X-ray tube windows and metallurgic processes), rendering Habachtal an increasingly interesting target.58 Reports were prepared in 1931 and 1932 by Professor Hans Leitmeier (figure 15) from Vienna University, at the request of Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau and the Schad/Burger team, with a possible joint venture in view.59 Leitmeier concluded that although the emeralds (figure 16) were not of a sufficient quality for economical mining, the extraction of beryl for metallic ore would be.

47File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal” (Beryll-Smaragd-Habachtal), Bundesministerium für Landwirtschaft, Regionen und Tourismus, Montanbehörde West, Salzburg (containing multiple documents from the period 1930 to 1978, hereinafter cited as File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg).

48File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

49Emil Sporn (b. 1869) studied at the Imperial and Royal School of Mining in Leoben and worked for the Austrian mining administration for several decades from 1896 until 1919. Beginning in 1920, he resided in or near Salzburg and worked for several mining companies. He was last referenced in the Archive of the City of Salzburg as of January 1945.

50File “Deutsch-Österreichische Edelsteinbergwerks Gesellschaft,” 1930, Munich Chamber of Commerce.

51Innsbrucker Nachrichten, Vol. 79, No. 181, August 8, 1932, pp. 5–6.

52Max Gaab v. Aktiengesellschaft für moderenen Bergbau and Meta Geist v. Aktiengesellschaft für moderenen Bergbau, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, May 21, 1930, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

53Notarized contract between Florian Prader and Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, June 26, 1931, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

54Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt, Vol. 49, No. 254, October 31, 1931, p. 2318.

55File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg; File “Status of Beryl as Ore Mineral” (Vorbehaltener Charakter des Berylls), Bundesministerium für Handel und Verkehr, 166.786 – O.B. – 1932, Austrian State Archive, Vienna (Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Vienna); Florian Prader v. Habach Weggenossenschaft, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 145/1932, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Gottfried Förster v. Angelo De Marchi, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 132/1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

56Julius Burger (1893–1977) was an engineer from Munich who had been involved in multiple mining projects in Austria, including coal mining near Lechaschau, Tyrol. He moved from Munich to Kitzbühel, Austria, in 1934 and later returned to Munich in 1947. Contemporaneous with his involvement with Christian Schad in the Habachtal emerald project, Burger remained engaged in several other mining ventures in Austria, such as one in Rettenbach, during the 1930s and 1940s. Assisting with the work in Habachtal was Austrian mining engineer Josef Heinrich Köstler (1878–1935). Mitteilungen über den Österreichischen Bergbau, Vol. 1, 1920, p. 44; Schmidegg, 1955; City Archive of Kitzbühel, pers. comm., 2020; City Archive of Munich, pers. comm., 2020.

57Christian Schad (1894–1982), a painter from Berlin, was apparently never active on site in Habachtal and is thus considered an investor in the undertaking. The investment in Habachtal emerald mining was initiated by his father Dr. Carl Schad (1866–1940), a notary from Munich, using Christian’s name mainly for tax reasons. Carl also invested large sums in various other mining projects, especially in Italy, which eventually led to substantial losses. Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Richter, 2020.

58Waagen, 1936.

59File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg (with only the 1932 report remaining available in the file). Hans Leitmeier (1885–1967) was a professor of mineralogy and petrography at Vienna University who dedicated a substantial percentage of his scientific research to alpine mineralogy and deposits. In addition to the 1931 and 1932 reports, Leitmeier in 1938 published a history of the Habachtal deposit, based largely on personal communication with Ernst Brandeis, grandson of Samuel Goldschmidt. However, such recollections were premised on memories some 35 years after the fact and not necessarily consistent with what can be derived from contemporaneous documentation. A further historical summary published by Leitmeier (1946) suffers from similar discrepancies, particularly as relates to the era between 1918 and 1939. See Hammer and Pertlik, 2014.

However, before further steps could be taken by Schad, Burger, or Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, the Swiss company was sued in the court in Mittersill by Rudolf Nocker and the entity Habach Weggenossenschaft, both of Bramberg, to recover alleged liabilities of 625 Austrian shillings arising in 1930 and 1931. When initial attempts to resolve the matter by leasing the property for 500 shillings per year were unsuccessful,60 the court named Hugo Ullhofen (1886–1973), a schoolteacher from Mittersill, receiver of the property. Ullhofen, in turn, leased the Habachtal emerald mine to Angelo De Marchi, a farmer and landowner from Milan,61 via a contract dated July 27, 1932, and running from August 1932 to October 1933.62 De Marchi had become aware of the property through Gottfried Förster, a self-described geologist active throughout Austria in searching for mining deposits and familiar with Habachtal since approximately 1930.63

As noted in materials prepared by De Marchi’s representative, attorney Dr. Gustav Freytag from Mittersill, the condition of the mine in 1932 was very poor. The mine had not been maintained for several years, and the galleries had been rendered nearly inaccessible by illegal mining activities and uncontrolled blasting (figure 17).64 De Marchi invested 25,000 Austrian shillings (equivalent to approximately US$1,790 at the time) and employed 15–20 miners to recommence operations, with Förster serving as mine manager.65 Authorization for recovery operations pursuant to the Trade, Commerce and Industry Regulation Act was sought through a September 1932 application.66 While that was pending, their first season’s efforts enabled the transport in October 1932 of 16 boxes of rough material with a total weight of 500 kg over the Alps to Italy.67

60Salzburger Chronik, Vol. 68, No. 112, May 17, 1932, p. 6; Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 62, No. 112, May 17, 1932, p. 6.

61Angelo De Marchi was born in 1882 in the municipality of Amatrice northeast of Rome. For the 1932 and 1933 period, addresses in both Milan and Rome are noted, and references can be found to the “De Marchi group of investors from Rome,” suggesting that De Marchi maintained both landholdings in Milan and business connections in Rome. File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

62Ullhofen, H., undated report covering 1930–1953, Archive of E. Burgsteiner, 2 pp.

63Gottfried Förster v. Angelo De Marchi, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 132/1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State. Gottfried Förster (1882–1942) was born in Bozen (Bolzano), then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now part of Italy. Förster was a painter by training but characterized himself as a geologist. The year 1924 saw him active in the Hollersbach Valley, east of Habachtal. By the 1930s, he had been operating as a purported exploration geologist for more than two decades in various parts of Austria, searching primarily for gold, copper, lead, and zinc deposits. Förster also applied for exploration permits and tried to sell the mining rights; some of his efforts were apparently deemed fraudulent. See Innsbrucker Nachrichten, Vol. 56, No. 152, July 8, 1909, p. 5; Tiroler Volksblatt, Vol. 49, No. 3, January 8, 1910, p. 8; Der Tiroler, Vol. 30, No. 36, March 25, 1911, p. 5; Tiroler Anzeiger, Vol. 10, No. 11, January 9, 1917, p. 6; Meraner Tagblatt, Vol. 38, No. 67, April 13, 1920, p. 1; Tiroler Anzeiger, Vol. 15, No. 57, March 10, 1922, p. 4; Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 54, No. 50, February 29, 1924, p. 4; Der Landsmann, Vol. 25, No. 106, May 8, 1924, p. 2.

64Gottfried Förster v. Angelo De Marchi, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 132/1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State. Dr. Gustav Freytag (1881–1947) was a judge in Salzburg before starting his own law firm there in 1925. In 1931 he moved to Mittersill in Pinzgau, where he continued to work as a lawyer.

65Ibid. See also Leitmeier, 1938; Lausecker, 1986; Hönigschmid, 1993; Lewandowski, 1997.

66File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

67Gottfried Förster v. Angelo De Marchi, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 132/1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

Not surprisingly, Schad and Burger were disquieted by the turn of events. Only two weeks into the De Marchi lease, Burger—again acting on behalf of Schad—instigated a regulatory proceeding at the mining administration in Wels that would protect their rights by:68

- Ensuring unrestricted access in accordance with the existing exploration permits, thus allowing for further development activities in the galleries (§ 100-103 of the mining law).

- Granting mining titles for the property, as would be feasible if beryl were declared to be an ore mineral of economic value covered by the mining law (§ 40-44).

Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau was involved in that proceeding, represented by attorney Dr. Max Duschl from Salzburg.69 Following negotiations, a preliminary ruling was made by the head of the mining administration (or Berghauptmann). On September 13, 1932, Dr. Franz Aigner (figure 18)70 deemed beryl to be covered by the mining law, a reversal of the administration’s earlier stance. The victory was short lived, however. An inspection at the mine the next day found only limited quantities of beryl, such that mining could not be considered of economic value and no mining privileges could be granted. De Marchi and his workers had apparently hidden some locations in the galleries where the tunnels crossed rocks with high concentrations of beryl and emerald. As a result, Schad and Burger maintained only a right of admission to the property for further development, in hopes of proving the mine to be economically viable for the extraction of beryl as beryllium ore.71

68File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

69Dr. Max Duschl (1870–1949) began his career as a lawyer in 1903 and continued in that field in Salzburg for nearly five decades. He was assisted by the Austrian mining engineer Othmar Kelb (1871–1947).

70Dr. Franz Aigner (1872–1962) studied law in Vienna and mining in Leoben. He began his career at the Austrian mining administration in 1903, serving as staff member in Wels from 1910 and as head of the department from 1913 to 1936, responsible for mining activities in the Habach Valley. Werneck, 1988; Günther and Lewandowski, 2002.

71File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

Yet another tactic was pursued by the lien holders Gaab, Geist, and Prader, the latter of whom also held exploration permits in the area. All were represented by Duschl. Seeking to maximize options, Duschl instigated litigation on behalf of Gaab and Geist at the court in Salzburg and on behalf of Prader at the court in Mittersill, with both suits seeking to overturn the Mittersill court’s decision to appoint Ullhofen as receiver.72 Although neither suit achieved greater rights for the petitioning lien and permit holders, given the nature of their interests, a procedural error identified by Duschl did cause the Mittersill court on November 20, 1932, to revoke Ullhofen’s appointment as receiver, which rendered invalid the contract between Ullhofen and De Marchi.73

In light of these developments, De Marchi appealed the decisions of both the Wels mining administration and the Mittersill court, while continuing his efforts to obtain a working permit for emerald recovery under the Trade, Commerce and Industry Regulation Act.74 Complicating such attempts were multiple additional lawsuits that entangled De Marchi during the same timeframe. His former mine manager Förster sued in May 1933, claiming inadequate compensation and a right under a June 1932 agreement to at least 25% of the mine’s profit.75 De Marchi was also involved in actions pending in Italy. For reasons beyond the scope of this study, after he had returned to Italy in October 1932, De Marchi risked imprisonment if he reentered Austria.76 Pursuit of the Austrian proceedings was not curtailed, however, as they could be handled locally by his attorney Freytag. A measure of success in his appeal of the Mittersill court’s ruling was achieved when the Supreme Court in Vienna reinstated the lease contract with Ullhofen in April 1933. De Marchi also finally obtained a working permit in July 1933.77 His appeal of the administrative ruling, on the other hand, was dismissed in September 1933 by the Ministry for Trade and Traffic on procedural grounds, and no final decision about the coverage of beryl under the mining law was made.78

Nonetheless, all of De Marchi’s legal machinations eventually came to naught as a result of the foreclosure of the property instigated by Gaab and Geist in May 1933.79 A foreclosure auction was held on August 31, 1933, and creditors Gaab, Geist, and Prader purchased the property for 12,806 Austrian shillings (approximately US$770 at the time), an amount less than the total outstanding liabilities.80 Because the other pending legal actions had precluded De Marchi from taking any practical steps to work the mine between the time his lease was formally reinstated in April and the August sale, any rights were effectively vitiated before they could be acted upon in practice.

The next several years saw a shifting of applicable exploration permits among interested parties, as well as the formation of a new entity. Certain existing permits held by De Marchi, Schad, Freytag, and Förster were terminated, while others held by Schad were extended. New permits were applied for by and/or granted to De Marchi, Schad, Freytag, and Förster.81

72Ibid.; Florian Prader v. Habach Weggenossenschaft, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 145/1932, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

73File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang.

74File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg.

75Gottfried Förster v. Angelo De Marchi, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, C 132/1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

76Ibid.

77File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell H1 2286-1933, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang. Notably, even the Austrian embassy in Rome and the Italian consulate in Innsbruck had become involved in the proceedings.

78File “Status of Beryl as Ore Mineral” (Vorbehaltener Charakter des Berylls), Bundesminsterium für Handel und Verkehr, 166.786 – O.B. – 1932, Austrian State Archive, Vienna. This action also saw intervention by the Italian Embassy in Vienna.

79Ibid.

80Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt, Vol. 52, No. 46, February 24, 1934, p. 503; Order, Bezirksgericht Mittersill, March 26, 1934, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry November 13, 1933, Mittersill land registry office. Smaragdbergbau Habachtal GmbH, the Austrian operating entity of the Swiss Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau, was formally dissolved in 1937. Salzburger Volksblatt, Vol. 67, No. 142, June 24, 1937, p. 8.

81Reported frequently in Montanistische Rundschau, Vols. 25–27, 1933–1935.

Property Under the Swiss Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft (1934–1939). By June 1934, the company Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft had been established in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, with a stated capital of 35,000 Swiss francs (approximately US$11,000 at the time) in 35 equal shares.82 The initial shareholders consisted of one Swiss citizen and four Germans: Prader, Geist, Gaab, Schad, and Burger.83 Schad contributed nine exploration permits in exchange for 14 shares, becoming a major holder, and the property was leased to Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft by owners Gaab, Geist, and Prader for a 30-year term.

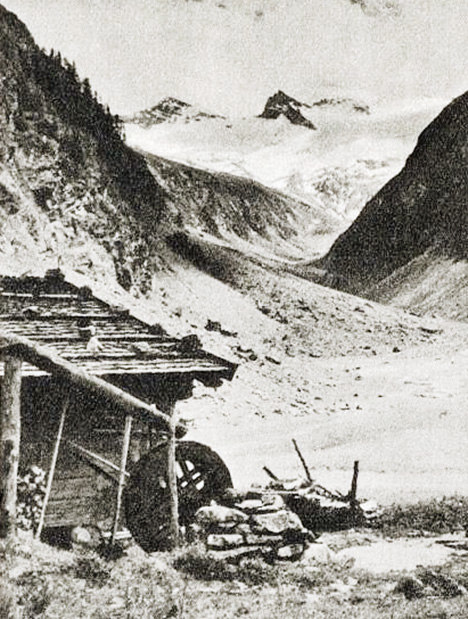

In 1935, Prader’s construction company from Zurich led endeavors to recommence operations at the Habachtal site (figure 19) on behalf of Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft. That year he requested from Müller a copy of the 1929 report84 and employed 10–12 workers to safeguard the property and form a plan for further activities.85 Subsequent years saw mining by Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft continued on a low level, led by Burger from 1936 to 1938 with five to seven miners mentioned in various documents for the 1936 to 1938 seasons.86 Local press from the period reported recovery of emeralds as gemstones (figure 20), with the permits contributed by Schad allowing Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft to pursue simultaneous exploration and development for the type of beryl mining that would be regulated by the mining law.87 Leitmeier published two additional studies during the era, focusing on geology and the genesis of emerald formation (figure 21).88 By 1939, Burger was no longer employed by the company. Operations that year, the final year of the firm’s work on site, amounted only to one engineer, one foreman, and several miners searching exclusively for emeralds.89 Freytag at that point served as legal representative for the company in Austria.90

Meanwhile, in 1937 the mine’s former owner Anton Hager had filed a lawsuit against Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft and Christian Schad, with Gaab, Burger, and Dr. Carl Schad also becoming involved.91 Details are vague, however, and no tangible substantive impact on the status of the mine or those connected thereto is apparent.

82Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt, Vol. 52, No. 150, June 30, 1934, p. 1811; Montanistische Rundschau, Vol. 35, No. 44, 1935, T.Mo. 44.

83File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg; File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1937 J5 – 5423, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1938 H1 – 12261, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

84Letter from W. Müller to A. Cissarz, December 25, 1939, Lagerstättenarchiv, Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien.

85File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang; Salzburger Chronik, Vol. 71, No. 202, September 3, 1935, p. 9; Alpenländische Rundschau, No. 621, September 7, 1935, p. 10.

86File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1936 A1 – 7587, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1938 H1 – 12261, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang; Salzburger Chronik, Vol. 73, No. 147, July 1, 1937, p. 6; Der Wiener Tag, Vol. 16, No. 5047, July 3, 1937, p. 5; Leitmeier, 1938.

87File Bezirkshauptmannschaft Zell am See, BH Zell 1938 H1 – 12261, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Völkischer Beobachter, Wiener Ausgabe, No. 169, September 2, 1938, p. 12.

88Leitmeier, 1937, 1938.

89Hanke, 1939.

90Montan-Handbuch für die Ostmark und die Südost-Länder, Vol. 20, 1940, Verlag Rudolf Bohmann, Vienna, p. 20.

91See Dr. Max Duschl v. Christian Schad, et al., Salzburg court, March 5, 1943, File CSSA 4826-2018, Christian Schad Stiftung Aschaffenburg, Museen der Stadt Aschaffenburg (a related suit over nonpayment of legal fees). The file for the primary case before the Salzburg court, characterized as “extremely complicated,” is no longer preserved in the archive of Salzburg Federal State. Land Salzburg, Landesarchiv, pers. comm., 2020.

HABACHTAL IN THE MODERN ERA (1940 TO PRESENT)

As the decade turned, recovery of beryl as an ore mineral was discussed several times between 1939 and 1941 at the Reichsstelle für Bodenforschung in Vienna, now controlled from Berlin,92 but no practical mining operations were undertaken.93 Burger now evaluated for Frankfurt-based Gold- und Silberscheideanstalt94 on the feasibility of mining for beryllium ore and even initiated efforts in 1940 to gain control of the mine, although those led to no tangible result either.95

In December 1940, the shareholders decided to dissolve Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft, and the process was finalized approximately one year later, rendering the shares worthless.96 During the 1941 to 1942 period, Gaab then purchased the third of the Habachtal property owned by Prader for 4,000 Swiss francs (approximately US$930 at the time), raising his share to two-thirds.97

No minining activities were documented during the rest of World War II. After the war, only limited mining was performed by a few individuals during the summer months. The mine was administered primarily by the pianist Hans Zieger (1892–1953, figure 22), who began working in Habachtal in late 1945 under a contract with Gaab.98 Zieger was also named administrator of the property by the U.S. Allied Commission for Austria, and he operated for many years with only one miner.99

92Danner, 2015.

93Danner, 2014.

94Later known as Degussa AG.

95File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg; File “Beryll Bramberg,” mining documents collected by W. Günther, Archive of the Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang.

96Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt, Vol. 59, No. 23, January 28, 1941, p. 186; Vol. 60, No. 12, January 17, 1942, p. 129; Richter, 2020.

97Notarized contract between Florian Prader and Max Gaab, October 29, 1941 (Munich) and May 22, 1942 (Zurich), Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State; Habachtal emerald mine file, entry November 25, 1942, Mittersill land registry office.

98Contract between Max Gaab, Franz Mayböck, Leo Weiss, and Hans Zieger, October 4, 1945, Archive of Erwin Burgsteiner, Bramberg.

99USACA 1945–1950, Records of the Property Control Branch of the U.S. Allied Commission for Austria, File Sch 398, Property of Meta Geist and Max Gaab, 24 pp. https://www.fold3.com/image/306445403?terms=Gaab and Hausmann, 1950.

Details of developments and activities at Habachtal after World War II are generally beyond the scope of this study and have been well covered by other authors.100 Various individuals or groups of individuals were involved on a temporary basis, and the possibility of mining the property for beryllium ore continued to come up for discussion in several forums, but nothing was pursued.101

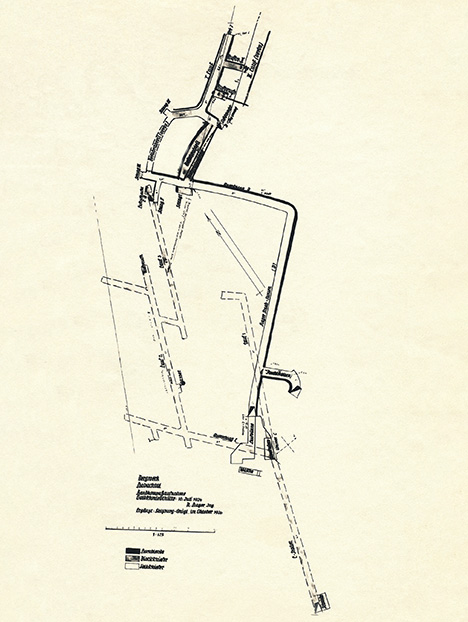

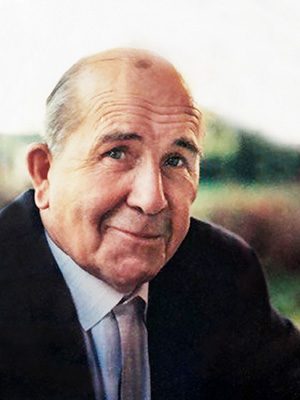

Meanwhile, upon Gaab’s death in 1953, his interest was split between his son Karl Gaab (1901–2000, figure 23), a Munich lawyer, and daughter Irma Sauter. Karl Gaab later bought his sister’s one-third share in 1962 and the final one-third held by Geist in 1963 (transactions formally registered in 1963 and 1964, respectively).102 Until his death, Karl Gaab remained the sole owner, attempting to protect the property to the extent possible. A comparison of maps prepared between the 1920s and the 1980s shows that as the decades passed, certain sections of the mine collapsed and additional areas were dug (figure 24).

At present, the Habachtal emerald mine is still in private possession and since 1985 has been maintained by the Steiner family from Bramberg. Since 2001, Alois Steiner and his son Andreas (figure 25) have overseen operations. Three to four individuals work in the D gallery from mid-June to September or October. The finds have included emeralds in matrix sold to mineral collectors (figures 26 and 27), as well as limited quantities of material used in both faceted (figure 28) and rough form to produce Habachtal emerald jewelry pieces.103

100See Eberl (1972), Pech (1976), Lausecker (1986), Grundmann (1991), Exel (1993), Lewandowski (1997), and Burgsteiner (2002).

101See File “Beryl-Emerald-Habachtal,” Montanbehörde West, Salzburg; Kirnbauer, F., Gutachten über das Beryllvorkommen Habachtal einschl. Aufschlußplanung, October 1, 1955, 18 pp.; File “Beryllium,” Österreichische Geologische Bundesanstalt Wien; Smaragdbergwerk für Atomindustrie, 1956.

102Habachtal emerald mine file, Mittersill land registry office, Archive of Salzburg Federal State.

103Andreas Steiner, pers. comm., 2019; Claudia Steiner, pers. comm., 2019.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Contemporary thinking about the history of emerald mining at Habachtal during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries has been based largely on perpetuated misinterpretation of several early references. Some look to the report by Aulitzky (1973) that mistook a 1593 landslide as an event destroying assumed emerald mines on the eastern slope of the valley, when in fact the disaster buried adits to the silver mines at Gamskogel on the western slope. Others rely on a 1727 mining chronicle by Brückmann, which in turn was based on editions of a booklet by Lehner (1669, 1702, 1718), all of which erroneously referred to green and violet fluorites from the Bach mining area near Donaustauf as emeralds and amethysts. Even aside from the mineralogical mistake, to connect Bach and Donaustauf in Bavaria to Habachtal in Austria is geographically baseless. However, this did not stop a number of well-known twentieth-century authors from repeating the error (see Scherz, 1955; Gübelin, 1956a,b), which is still found in more recent texts.104

Yet another misinterpretation, albeit more subtle, derives from the first known written but unpublished reference to Habachtal emeralds in a 1669 letter by Anna de’ Medici, which mentions Danish-Italian scientist Niels Stensen’s journey to the region. For some to have stretched mention of an occurrence in the original language to imply mining is unjustified. Only limited collection by locals during the era seems supportable. The first publication on the occurrence was written by Schroll (1797) as part of a geological and mineralogical description of Salzburg, and the primary source was identified some decades later in the 1820s.

Thereafter began the mining history at Habachtal, a saga fraught with twists, turns, starts, stops, hopes, and disappointments (see table 2). The property was held by the state in the first half of the nineteenth century and sold in 1861 to jeweler Samuel Goldschmidt from Vienna, who was the first to undertake systematic recovery of emeralds. Open-pit activities began in 1862, followed by tunneling, but efforts were canceled after a few years of limited success. In 1896, Goldschmidt’s heirs sold the Habachtal property to the British firm Emerald Mines Limited, which in turn was owned or controlled by a succession of two different British groups. The first, from 1896 to 1906, was the London-based diamond merchant Leverson, Forster & Co. and individuals connected therewith. Mining was performed in the summer months for seven or eight years, with some intervening inactive seasons. Legal troubles led to the transfer of shares in 1906 to the Northern Mercantile Corporation Limited of Manchester. Under new leadership, only limited mining without great success was pursued in 1906 and possibly 1907. By 1913, mounting liabilities, particularly to the municipality of Bramberg, resulted in the mine being returned to public ownership before being resold in the ensuing decades to a series of Austrian, German, and Swiss private individuals and entities.

104Stehrer, 2000.

After World War I, mining recommenced under Hager, an Austrian citizen, and his half-brother Staudt, a German citizen, with the production of talc for industrial purposes also being considered. Detailed geological reports of the locality and business plans were prepared, but the requisite investment for actualization never materialized. In late 1927, the property was purchased by the Swiss firm Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau. The outcome, however, was just one month of mining in 1927 and a few weeks in 1928 and 1929 before liabilities and legal troubles overtook any hope of a sustainable business. Rivalries between multiple groups interested in the property and its prospects, not only for emeralds but also for beryllium as an ore mineral, erupted in a welter of litigation and regulatory proceedings. Key players included the team of Schad and Burger, who were particularly active in seeking exploration permits; Gaab, Geist, and Prader, who held liens in the property as a consequence of extending loans to Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau; and the Italian investor De Marchi, to whom the property had been leased in 1932 by the court-appointed receiver Ullhofen. In the midst of the litigation and administrative actions, De Marchi was only able to engage in active mining for the single 1932 season.

Eventually, a foreclosure initiated by Gaab and Geist resulted in a public auction in 1933, where the property was purchased by Gaab, Geist, and Prader, with ownership thereafter held in three equal shares. Another Swiss entity, Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft, was established in 1934 in Schaffhausen, with the majority of those individuals pursuing mining at Habachtal joining together as shareholders. Notably, Schad contributed a number of exploration permits, while Gaab, Geist, and Prader leased the property to the company. Nonetheless, only limited production efforts were undertaken between 1935 and 1939, terminating in 1940 with the common refrain of insolvency and the dissolution of Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft. Control of the property narrowed down to the three owners Gaab, Geist, and Prader, before subsequently being consolidated in the Gaab family. The Habachtal property finally ended up as private German property, maintained today by the Steiner family from Bramberg.

In summary, it appears that from 1862 to 1939, active mining took place at Habachtal only during a series of relatively brief and disjointed periods:

- For a few years starting in 1862 by Goldschmidt via open-pit methods and later tunneling

- In the 1870s by lessees contracting with Goldschmidt’s heirs

- From 1896 to 1902 by the British entity Emerald Mines Limited under the control of Leverson, Forster & Co., which worked underground using four galleries

- In 1906 and possibly into 1907 by the Emerald Mines Limited under the control of Northern Mercantile Corporation Limited

- Intermittently between 1920 and 1927 by Hager and Staudt

- Briefly in 1927 and 1928 or 1929 by the Swiss firm Aktiengesellschaft für modernen Bergbau

- In 1932 by De Marchi

- From 1935 to 1939 by the Swiss entity Smaragd Aktiengesellschaft

The success of any of the eras, and the broader question of the value of the Habachtal property for mining purposes, are difficult to intuit from the historical record left behind. Problems in that regard derive both from the backgrounds of the principals and from the disparate purposes underlying different reports or appraisals. As to the participants, it is notable that only Goldschmidt and the London-based diamond merchants had deep roots in and knowledge of the gemstone market. Later owners and directors were merchants hailing from other fields—bankers, civil engineers, and attorneys—who in turn were assisted by civil, technical, and mining engineers, geologists, and mine foremen. Notably absent were any skilled gem merchants truly able to assess the commercial value of the mined rough.

Concerning the different purposes of reports and appraisals, there is a marked divergence between figures or values offered in a regulatory sphere versus an investment setting. For example, Emerald Mines Limited reported to the mining administration that material was nearly worthless to minimize payment of taxes and fees. Mining administrator Aigner took a similar view, commenting that emerald mining in Habachtal had never been profitable. Leitmeier reported the same, but his remarks might have been biased toward starting commercial production of beryl as an ore mineral. The counterpoint provided by figures aimed at drawing investment is dramatic. By way of examples, in 1920 Autzinger estimated production of 5 kg of export-quality emeralds per week, and in 1930 Deutsch-Österreichische Edelsteinbergwerks Gesellschaft calculated profitability at several hundred thousand marks per year. Such inflated figures led to repeated financial failures for both companies and individuals, with perhaps only Müller’s 1929 report having identified the real problem—only 2% of the emeralds recovered were of facet quality.

In the final analysis, it seems that between 1862 and 1939, emerald mining at Habachtal was only economical, at least in part, for brief periods under Leverson, Forster & Co. and De Marchi. That said, it is likely that even with the limited quantity of gem-quality rough, small-scale mining guided by experienced mining engineers or geologists, combined with distribution of emeralds in matrix for collectors and facet-quality rough for gem cutters by trade experts through the right channels, could have been profitable. That is the state of affairs at Habachtal today.