Natural Near-Colorless Type IIb Diamond

While colorless to near-colorless HPHT laboratory-grown diamonds usually contain detectable boron impurities (classified as type IIb; see S. Eaton-Magaña et al., “Observations on HPHT-grown synthetic diamonds: A review,” Fall 2017 G&G, pp. 262–284), it is uncommon to encounter a boron-bearing diamond of natural origin due to its rarity (0.02% of natural gem diamonds; E.M. Smith et al., “Blue boron-bearing diamonds from Earth’s lower mantle,” Nature, Vol. 560, No. 7716, 2018, pp. 84–87). The boron concentrations in natural diamonds are generally low (typically <1 ppm), but boron is such an efficient coloring agent that it imparts a blue color to most type IIb diamonds. However, exceptions still exist. For example, when boron absorption is accompanied by absorptions from plastic deformation, the combined effects may give rise to other colors (e.g., yellowish green; Spring 2012 Lab Notes, pp. 47–48; see also Summer 2009 Lab Notes, p. 136). Occasionally, some type IIb diamonds are near-colorless because their boron concentrations are too low to cause a blue color (e.g., E. Fritsch and K. Scarratt, “Natural-color nonconductive gray-to-blue diamonds,” Spring 1992 G&G, pp. 35–42), but they are far from common. Therefore, any near-colorless type IIb diamond submitted to a gem laboratory should be given particular attention to determine its possible lab-grown origin.

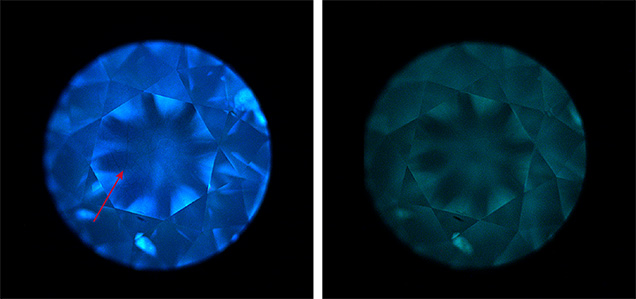

Recently, we had the opportunity to examine such an example. This 0.24 ct round brilliant cut had an I color grade due to its grayish component, usually seen in natural type IIb diamond. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) absorption spectroscopy detected a weak band at 2802 cm–1 (figure 1), characteristic of uncompensated boron, and identified the sample as type IIb. The diamond was inert to both long- and short-wave ultraviolet radiation. When observed with the DiamondView, it exhibited blue fluorescence and moderate blue-green phosphorescence (figure 2). The dislocation networks observed on the table (figure 2, left), typically seen in some natural type IIa and IIb diamonds but not previously described for lab-grown diamonds, suggest a natural origin. Further evidence of natural origin came from photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy and inclusion analysis.

Multiple laser excitations (473, 532, and 633 nm) were used to characterize its photoluminescence features at liquid nitrogen temperatures. The PL spectrum measured with a 473 nm excitation revealed the presence of nitrogen-related defect H4 (496.0 nm) (figure 3, top). PL spectroscopy using a 532 nm laser (figure 3, bottom) revealed the occurrence of GR1, NV0, and a sharp peak at 648.2 nm that is probably related to interstitial boron, all of which have been documented previously in type IIb diamonds (S. Eaton-Magaña et al., “Natural-color blue, gray, and violet diamonds: Allure of the deep,” Summer 2018 G&G, pp. 112–131). Nickel defect-related peaks (883/884 nm), a common feature in HPHT laboratory-grown diamonds of various colors, were not detected with any of these excitations.

Magnification indicated several solid inclusions (figure 4), mostly in the crown, that resulted in its SI1 clarity grade. The inclusion scenes were consistent with those described in natural type IIb blue diamonds (Smith et al., 2018). Namely, they tended to show a tiny satellite-like appearance composed of the main inclusion and accompanying decompression cracks. Raman spectra using a 532 nm laser revealed that two of these inclusions were coesite (figure 5). This feature confirmed the diamond’s natural origin. Coesite is a relatively common inclusion in lithospheric diamonds that formed at depths of ~150–200 km. However, recent studies show that type IIb diamonds have a sublithospheric origin and are formed in the upper part of the lower mantle (Smith et al., 2018). For type IIb diamond formed at such depths, the coesite inclusion has not been considered to be in its original pristine form, but rather the back-transformation product from stishovite. Another inclusion showed bands matching roughly with perovskite (CaTiO3) (figure 5), but its precise mineralogy was difficult to determine. This is because the Raman spectra of perovskite and CaSiO3 perovskite, both of which have been described in sublithospheric diamonds, are very similar (F. Nestola et al., “CaSiO3 perovskite in diamond indicates the recycling of oceanic crust into the lower mantle,” Nature, Vol. 555, No. 7695, 2018, pp. 237–241). No matter what exact mineral this inclusion corresponds to, its occurrence implies a sublithospheric origin for the host diamond. Other mineral inclusions could not be identified, probably because of their depth within the diamond.

Due to the scarcity of natural type IIb diamonds, any near-colorless diamond that contains boron detectable by FTIR spectroscopy should be given close attention to determine its origin. The near-colorless type IIb diamond examined here, though rarely encountered, was identified as natural on the basis of its gemological and spectroscopic characteristics.