A New Discovery of Emeralds from Ethiopia

In recent years Ethiopia has gained considerable attention in the gem trade for large amounts of high-quality opal from an area near Wegel Tena (B. Rondeau et al., 2010, “Play-of-color opal from Wegel Tena, Wollo Province, Ethiopia,” Summer 2010 G&G, pp. 90–105). Apart from opal, emeralds have been sporadically mined, near Dubuluk, for more than a decade. This deposit is located about 80 km from the Kenyan border. Gemfields has been exploring this deposit since July 2015 (Fall 2012 GNI, pp. 219–220).

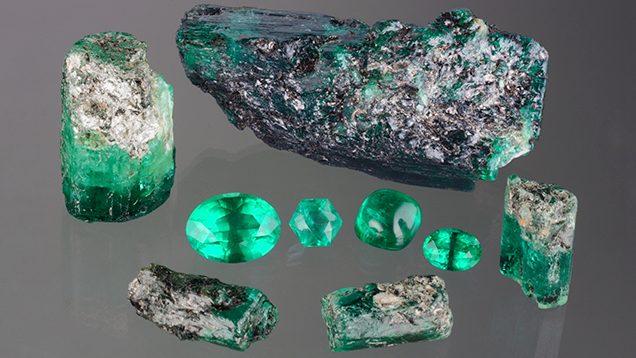

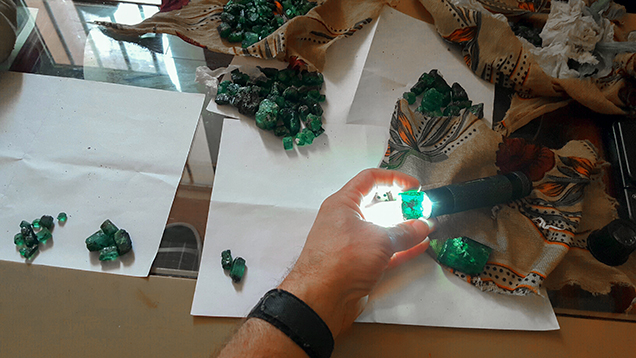

A new deposit of high-quality emeralds (see figure 1) has been found in the rural villages of Kenticha and Dermi, in the Seba Boru district (figure 2). In November 2016, author MN and business partner Daniel Kifle visited the local trading town of Shakiso, where Ethiopian gem merchants gather to legally buy and sell emeralds that are mined several kilometers away. Shakiso is located about 160 km north of the Dubuluk emerald deposit. The mining area is divided into a few “associations.” Each consists of a manager and several members who control the actual mining and distribution of the emerald rough. After the rough has been sorted, it makes its way first through Shakiso before being sold to dealers in the capital city of Addis Ababa, about a 12-hour drive from the mining area.

According to Tewoldebran Abay, the mineral marketing director of the Ministry of Mines, Petroleum and Natural Gas, more than 100 kilograms of emerald rough have been produced to date. Mining still is done the traditional way using hand tools, without heavy machinery.

Samples from the new deposit, acquired from multiple independent sources, were examined at GIA’s Carlsbad and Bangkok laboratories. Even though most of the material is commercial grade, lighter in saturation, and moderately to heavily included, fine gem-grade crystals of exceptional size, color, and clarity (see figures 1 and 3) are obtainable and can produce stones that do not require clarity enhancement. Many of the rough crystals were completely covered in dark biotite crystals, but had an extremely pleasant green color when examined with transmitted light. However, these Ethiopian crystals often do not yield large clean stones because their interior is riddled with dense, dark biotite mica crystals. Some show a double termination, but most are broken and heavily included on one end. Usually only one end of the crystal is clean enough to yield faceted gems. The matrix minerals attached to some of the emeralds were identified as dark brown to black biotite flakes, quartz, and kaolinite.

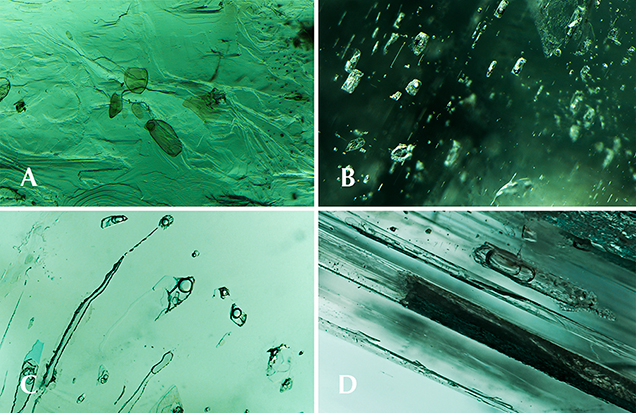

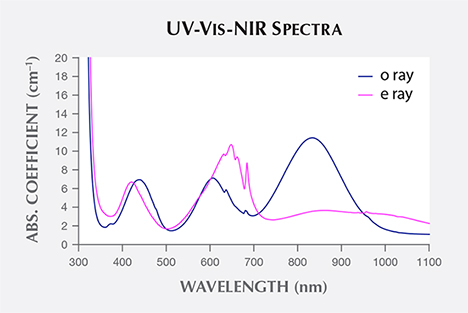

These emeralds are very similar in appearance to other schist-hosted emeralds—in particular, those from Brazil and Zambia. Among the faceted and rough samples examined, blocky multiphase inclusions and irregular biotite crystals were the most common microscopic features observed (figure 4). Otherwise, the gemological properties were very consistent with emeralds, including an average specific gravity of 2.73 and a refractive index of 1.581–1.589. These emeralds were generally inert to long- and short-wave UV exposure due to their moderately high iron content, which is typical of schist-hosted emeralds. UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy results (figure 5) were consistent with emeralds colored by chromium and vanadium. The Fourier transfer infrared (FTIR) spectrum was consistent with beryl, as expected, but did not reveal any other diagnostic features.

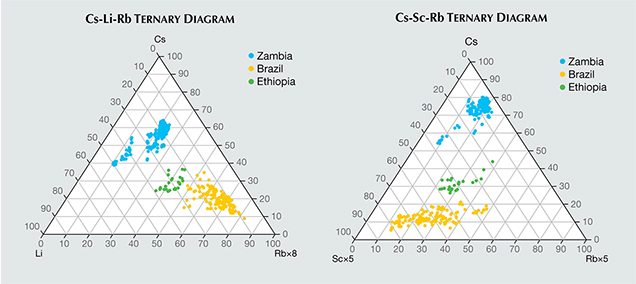

Quantitative trace element chemical analysis was performed with a Thermo Scientific iCap Q inductively coupled plasma–quadrupole mass spectrometer combined with a New Wave Research UP-213 laser ablation unit. The analyses were compared to data from other known sources using GIA reference samples, including Zambian and Brazilian schist-hosted emeralds. Based on the results, it was possible to separate the new find of Ethiopian emeralds from other sources by comparing trace alkali metals and some transition metals (figure 6).

Due to heightened tensions and fear of price instability, most of the mine area was temporarily closed by a joint effort of the mining associations and the local government from early November through December 2016. It has been reopened, but now all dealers, including Ethiopian dealers, need written permission to enter the Shakiso area for buying. The law is vigorously enforced, and penalties are severe.

This exciting discovery in Ethiopia will provide a new source of large, high-quality emeralds for the gem and jewelry trade. So far, this deposit appear to be quite promising, as significant production was seen in the recent gem shows in Tucson, Bangkok, and Hong Kong. Only time will tell how significant this deposit will be.