Importance of the Secondary Market for Fine Gems

At the AGTA show, Dave Bindra (B&B Fine Gems, Los Angeles) showed us some exceptional items he recently sourced from the secondary market. These are previously sold goods recirculated back into the market by the former owners or their heirs.

Bindra also updated us on his perception of U.S. traders’ reaction the withdrawal of sanctions against Myanmar (Burma) and what that means for U.S. dealers like him. According to Bindra, most U.S. dealers greeted lifting of the trade embargo with enthusiasm as they can legally import and trade Burmese rubies again. Prior to this they were limited to trading items that had come into the country “pre-ban.” Bindra doesn’t expect prices to come down; rather, he projects they will strengthen as American demand and consumption of Burmese goods grows. He noted that during the ban, some consumers and certain major brands stopped consuming rubies altogether, basically because they weren’t open to consuming rubies from sources like Mozambique, which has become a prolific source of commercial-to-fine grade gems. Now that the ban is lifted, Bindra hopes many of these companies will start buying and selling Burmese rubies again. The main issue now is the very limited supply coming out, but he says there’s definitely a strong market for fine-quality stones.

Bindra highlighted some exceptional pieces at his booth to illustrate the importance of the secondary market for his inventory. The company also procures gem materials from currently active mining areas, but the secondary market is important for larger, more important stones, which are scarce as a percentage of new production. As an example, he shows us a fine, oval-cut, 55.52 ct copper-bearing tourmaline from Mozambique (figure 1). He notes this particular stone came out of the original 2007 production from Nampula Province, northeastern Mozambique, near the village of in Mavuco (see B.M. Laurs et al., “Copper-bearing (Paraíba-type) tourmaline from Mozambique,” Spring 2008 G&G, pp. 4–30).

B&B actually sold this stone about seven years ago, and was lucky to reacquire it when the opportunity arose in 2016. Bindra considers this fortunate as there is no production from this deposit today and it would be impossible for them to find an item like this, other than the secondary market.

Another example he cites is a beautiful 5.06 ct trillion-cut benitoite (figure 2). This gem—a barium titanium silicate—is typically colorless to blue, and is noteworthy for its high refractive indices, moderate birefringence, and strong dispersion. It comes from just one mine, located in San Benito County, California (see B.M. Laurs et al., “Benitoite from the New Idria District, San Benito County, California,” Fall 1997 G&G, pp. 166–187). The benitoite mine has been closed for years. Bindra describes this 5 ct as an “astronomical size for this deposit”—the typical size range of commercially available finished gems from this mine was between 0.30 and 1.70 ct. He noted that this gem was a prized possession of an original mine owner.

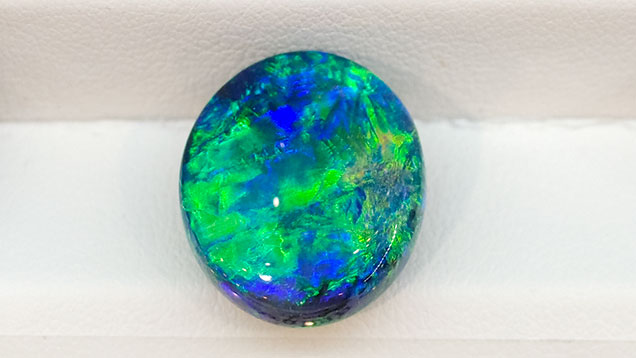

Bindra also showed us a couple more recirculated pieces: a fine 15.06 ct double-sided black opal cabochon (figure 3) with broad flashes of play-of-color from Australia’s Lightning Ridge and a 19 ct antique-cut Brazilian Imperial topaz. This last stone was old, unheated material from Ouro Preto. The stone came out of an old collection and was a little over 20 ct. They were able to recut it with minimal loss of weight to significantly improve luster and brilliance. Bindra told us these gems underscore the importance of the secondary market for his inventory. While it doesn’t supply the day-to-day production B&B needs, it does produce truly exceptional items from time to time. He noted that fine colored gemstones always retain their value, which is why B&B is often able to reacquire items over a period of time. He always keeps this in mind whenever selling rare, esoteric gemstones.

Next, Bindra showed us one of the most exceptional stones he’s had in years: a 10.22 ct cushion-cut Brazilian alexandrite. He adds that B&B has trouble fulfilling orders for 6 mm (approximately 1.00 ct) round alexandrite with current Brazilian production, so finding a 10 ct size is really an anomaly. According to Bindra, it came out of an old collection in Japan, where it sat in a safe for 20 years. He said he “couldn’t write the check fast enough” to get it into B&B’s inventory. In this case, there was no need for repolishing. The gem is unusual not just for its size and the quality of its color change, but also because of its brilliance. He notes that Brazilian alexandrite of this rich blue-green to reddish purple color tend to be “over dark” and lack life. This stone was faceted with a typical Portuguese pavilion, which confers considerable brilliance. Due to these factors, Bindra adds, the wholesale value of a truly fine gemstone like this is well over $55,000 per carat.

Finally Bindra shows us a 20-ct-plus star sapphire with a sharp six-rayed star, strong blue bodycolor, exceptional translucency, and a well-proportioned, high-domed cabochon shape. It’s another piece that’s “come out of recirculation,” says Bindra. He suspects the current marketplace scarcity of fine blue star sapphires is due to a newly discovered heating process, leading to a lot of fine-color examples being recut into faceted gems. He cites an example of a 23 ct star sapphire, which might be heated and refashioned into a top-gem royal blue color faceted stone in the 10–15 ct range. For some people, that’s more desirable, so stars are becoming rarer. Not every stone can be heated and improved, as they might break due to the unforeseen way inclusions react to the heat.

Bindra sees strong demand from the top one percent of consumers. He notes that exceptional gemstones are in very high demand, as more than ever people find value in hard assets—fine art, classic automobiles, fine wine, high-end watches, important diamonds—and colored gemstones are “in that same conversation.” Bindra professes some skepticism about the middle of the market, where commercial to mid-grade material is not moving as well. At the top end of the market, high-end colored gemstones are difficult to find because of competition from overseas—from new markets, from new capital—especially in Southeast Asia, where there is a cultural affinity for consuming fine colored gemstones.