The Chinese Soul in Contemporary Jewelry Design

ABSTRACT

When the same gems and precious metals are used in jewelry, design is the element that ultimately distinguishes one piece from another. Real success is measured not only by the value of its materials but also by the character and quality of the design and craftsmanship. Once considered a weak point of China’s gem and jewelry industry, design has seen tremendous progress over the last decade. Benefiting from the availability of more gem materials and the power of a rapidly growing consumer market, Chinese designers now have the freedom to develop their design concepts and craftsmanship skills. Designers from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan share the bond of cultural identity and have found ways to create jewelry that expresses the Chinese soul.

INTRODUCTION

From dangling hair ornaments to exquisite jade pendants and splendid crowns, jewelry has always served as personal adornment for the Chinese people, from ordinary citizens to royal families (figure 1). Throughout the civilization’s 5,000-year history, masters of jewelry design and manufacturing have emerged continually, applying innovations while developing their skills.

China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) followed more than a century of social and economic upheaval that hindered almost every aspect of national growth. During this period, jewelry came to represent capitalism, and wearing it was considered offensive. Designers and craftsmen avoided persecution by simply stopping their work.

In the last decades of the 20th century, the Chinese gem and jewelry industry experienced a dramatic upswing. By the end of the 1990s, there were about 20,000 jewelry businesses and some three million people involved in the trade (Hsu et al., 2014). The country’s jewelry markets became saturated with similar products, many of low quality (J. Bai, pers. comm., 2013).

This lack of innovation caused a sense of stagnation, which led some industry pioneers to find a new approach. Professional training and degree programs in jewelry design have been offered since the early 1990s. Over the last 10 years, many leading universities and art academies have formed their own jewelry design and manufacturing departments to serve an expanding market. Foremost among these are Tsinghua University, China University of Geosciences, and China Central Academy of Fine Art. Jewelry competitions have been created to foster the development of young talent. Many companies have invited designers from Hong Kong and overseas to bring their skills to China and to train locals (figure 2). At the same time, Chinese artists have begun going overseas to the UK, the United States, Italy, and Germany to study Western jewelry manufacturing.

It is widely believed by domestic consumers that Chinese jewelry designs should capture the “Chinese soul.” This concept is a reflection of the native culture, “a collective programming of the mind” that distinguishes a group of people (Hofstede and Bond, 1988). Rather than being genetically transferred, cultural inheritances can only be acquired by native experience. For thousands of years, the core values of Chinese culture have not fundamentally changed. The process begins at birth and continues throughout a person’s life, as one gains a deeply rooted understanding of Chinese culture, including its distinct traditions, philosophy, religions, and preferred materials. This understanding allows the native-born designer to easily and naturally incorporate traditional elements into jewelry for domestic audiences and accurately interpret their meanings (see figure 3, for example). The spiritual message carried by a piece of jewelry can be reflected by combining some Chinese design elements, but this is not always the case. Simply using Chinese elements is not enough: The designers must think in the Chinese way.

In 2010 China overtook Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy, after the United States. China is now also the second-largest jewelry market and is projected to become the largest by 2020 (“Chinese jewelry firms…,” 2014). To cater to the rapidly expanding market for luxury goods, the Chinese began developing their own innovative jewelry designs.

CHINESE DESIGN ELEMENTS

One recent jewelry trend is to incorporate Chinese elements such as dragons, the phoenix, bamboo, and Chinese characters into their products. Many award-winning pieces from international design and gem-cutting competitions feature these elements (Chen, 2014). While several Western designers have embraced traditional Chinese symbols, they sometimes do not apply or combine them properly, making them less meaningful. According to Hong Kong jewelry designer Dickson Yewn, “Jewelry is a new way to interpret a culture that has been suppressed for decades.” He believes China is a fundamental resource for jewelry design and that after prolonged social upheaval, it is time to recapture its glory.

Trained as a painter, Yewn has always been interested in Chinese culture and history (figure 4). Having spent years in the West, he has a deep appreciation for its culture but prefers to create jewelry that is distinctly Chinese rather than mixing cultural designs (World Gold Council, 2014). He is also engaged in reviving traditional Chinese jewelry craftsmanship.

While many designers focus on generating new concepts, Yewn digs deeply into native traditions and fuses them with contemporary luxury. His common themes include lattice patterns, paper cutting, Manchurian motifs, and peonies—the Chinese national flower. One of his collections, “Lock of Good Wishes,” is based on such traditions (figure 5). The earliest known lock in China was uncovered from a tomb dated 3000 BC. While the basic function of the lock has not changed, the style, materials, and craftsmanship have continued to evolve, and its meaning as a decorative motif has broadened. As a symbol of security, a lock also represents good health and longevity in Chinese culture. Newborns are given precious metal lock pendants to “lock” health and happiness into their lives forever. This type of pendant is still one of the most popular jewelry gifts for babies in China.

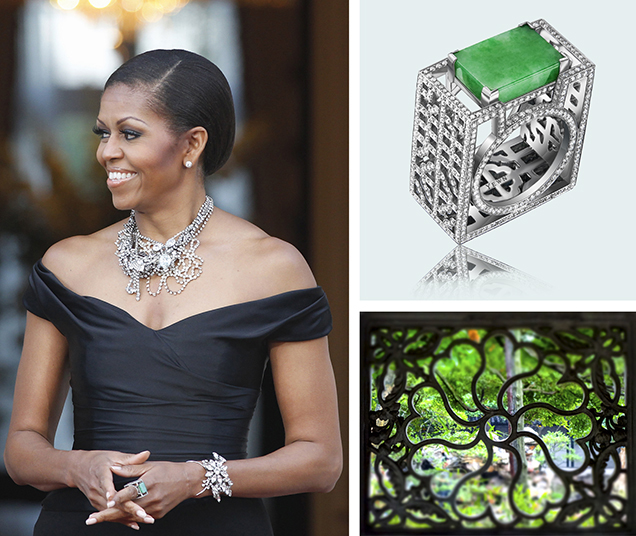

Yewn’s jadeite and diamond “Wish Fulfilling” ring features a traditional lattice window shank. Lattice windows were a common sight in ancient Chinese gardens, their delicate patterns inviting the viewer to look through and enjoy the beautiful scenery within. They originated in southern China, home of the Classical Gardens of Suzhou. These private gardens, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, date from the 11th through 19th centuries. Their lattice windows are among the most important elements, framing the view with a mysterious veil (figure 6). Yewn borrowed this concept from the garden masters, intending the ring to create a connection between the wearer’s mind and the outside world.

This ring was a favorite of First Lady Michelle Obama, who wore it in 2011 when President Obama hosted a banquet for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. The ring caught the attention of many notable guests that evening (Adducci, 2011).

TRADITIONAL CRAFTSMANSHIP

China has a long history of using gold and silver in jewelry design, and gold still dominates the domestic jewelry market. Imperial artisans were once able to spend considerable time on a piece of jewelry commissioned by the emperor. Today very few can afford to practice time-consuming traditional craftsmanship. Yet the rise of mainland China’s luxury market is changing this by encouraging the adoption of classic techniques.

One of these is filigree inlay art (figure 7). This combines two crafting skills: The first is filigree, the use of gold or silver threads of different weights. The second is inlay work, which involves setting stones and carving or filing precious metals around them. The artist responsible for the revival of this technique is Master Jingyi Bai (figure 8).

Master Bai’s interest in both painting and pattern serves as the basis for her design life. As an art school student of precious metals, she gained some knowledge and skills, but she felt they were not enough to make her a successful master goldsmith and designer. Over the next 40 years, she perfected her technique in a filigree inlay art factory, where she was trained by older-generation master goldsmiths. In 2008, filigree inlay art was designated the Intangible Cultural Heritage of China, and Master Bai was named the official Representative Inheritor. Master Bai’s participation in promoting filigree inlay art accelerated in 2009, after she began designing for well-known Chinese jade jewelry brand, Zhaoyi. These two events took her career to new heights.

Master Bai has created many replicas of historic filigree inlay art pieces. Today, she works full-time in her studio as Zhaoyi’s chief designer of filigree inlay products (figure 9). Her jewelry is thoroughly Chinese, from the materials to the themes and craftsmanship. Her filigree inlay jewelry set “Royal Classic: Ripping Cloud” won Best Craft Inheritance Award at the second National Jewelry Processing Craft Competition in 2011.

Master Bai’s design philosophy is that a piece must succeed on its own in the market. To reach this goal, she considers both the quality of the craftsmanship and the contemporary composition. She says the first filigree inlay jewelry suite she designed and made for Zhaoyi was purchased—unexpectedly—by a young couple. For years, China’s younger generation, especially in large cities, considered high-purity gold jewelry somewhat out of fashion. This was largely due to the lack of creative design. Today, young consumers prefer innovative gold jewelry.

DEPICTIONS OF CHINESE PHILOSOPHIES

Chinese jewelry designers benefit from many sources of inspiration. Poems, fairy tales, and paintings, for instance, are full of generations-old Chinese philosophies. Yue-Yo Wang (figure 10), a jewelry designer from Taiwan, has devoted herself to traditional Chinese jewelry design using such themes. She combines Chinese knotting art with modern design and manufacturing techniques to create her own pieces, giving each of them its own story.

In China, knotting art can be traced back to around 1600 BC. Today the younger generation is embracing this ancient art with renewed interest. Wang began with knotted teapot covers and then developed her product lines to include clothing and decorations. She eventually realized that knotting art could be combined with modern jewelry manufacturing methods (figure 11), and established Wang Yue-Yo Creative Jewelry Design in Taipei about 20 years ago. The flagship store opened in 2007 in Beijing. Since then her company has greatly expanded its number of retail outlets. In 2012 Wang formed the Taiwan Creative Jewelry Design Association, hoping to attract designers focused on artistry and a desire to spread Chinese culture to the rest of the world (figure 12).

Wang’s designs feature traditional Chinese symbols with elements of Chinese knotting art, such as long tassels and thread patterns. Gem materials often seen in her designs include opal, coral, jadeite, tourmaline, and chalcedony (figure 13). These gems are time-honored favorites of the Chinese people. Wang believes that every gem has its own spirit, and she is inspired to find it and express it through her jewelry.

Wang’s designs, with their balanced and harmonious color and materials (figure 14), reflect the philosophy laid out circa 500 BC in Zhong Yong, translated as The Doctrine of the Mean. Zhong symbolizes impartiality, while Yong represents permanence. This classic text was one of the first books composed by the disciples of Confucius and has been a central tenet of the philosophy ever since. Intellectuals practiced this philosophy in their daily lives, while the ruling class applied it to management strategy. After generations, Confucian philosophy became the barcode of Chinese culture and remains so to this day. This is reflected in art, symmetry patterns, and motifs. The aesthetic standard the Chinese people hold is also based on this philosophy. Chinese painting, calligraphy, and carving all reflect this standard, which is exemplified by Wang’s jewelry.

INNOVATIVE DESIGN TECHNIQUES

Shirley Zhang, one of China’s leading designers (figure 15), has been in the industry since the 1990s. She has created her own patented jewelry-making methods while importing Western techniques. Zhang’s small factory, Meiher Jewelry Styling Research Center, performs every manufacturing step from design to finished product. This allows Zhang to test and develop new manufacturing processes.

These efforts proved worthwhile when Zhang’s masterpiece, “Dancing on the Flowers” (figure 16), won a special award at the 2012 National Gems & Jewelry Technology Administrative Centre jewelry design and manufacturing skills competition. The suite, accented with bee and flower designs, includes a shoulder drape, a cuff bracelet, and a pair of earrings. In Chinese culture, bees symbolize the essential character trait of diligence. This design competition was a salute to the accomplishments of the Chinese gem and jewelry industry over the previous 20 years, and Zhang used the bees to represent the industry’s diligent work. A variety of gemstones and setting techniques were applied. Of these items, the shoulder drape is the most breathtaking. It features patented “dumbbell” buckle links between the honeycomb cells, allowing the piece to move freely and drape perfectly on the wearer’s shoulder, giving the feeling of silk fabric rather than gold. The wearer can also reshape the piece by disconnecting and reattaching the links in various combinations for versatility.

Another patented technique applied to this shoulder drape is the “honeycomb” setting of the colored stones in the flowers, allowing more light to pass through the stones. The color and setting are equally attractive on both sides of the petals, resolving an age-old design and setting challenge.

Zhang’s experience working overseas opened her eyes to the Western jewelry industry and inspired her to apply some of its methods. One example is her use of plique-à-jour (figure 17). Developed in France and Italy in the early 14th century, this technique differs from standard enameling in that the precious metal frames that contain the glass material have no backing, allowing light to pass through. This creates the stunning effect of a miniature stained glass window within a piece of jewelry. Plique-à-jour is commonly applied to jewelry and pocket watches by Western jewelers, including internationally known brands such as Van Cleef & Arpels, Cartier, and Tiffany. Zhang and her team spent years researching and testing this technique. Her company is now the only one in mainland China that applies it to jewelry.

Zhang’s jewelry emphasizes the fine colors of the gemstones, aiming for harmony. She also likes to coordinate colors with different shapes or cultural themes and to express her love of nature through her designs. Her styles blend innovative craftsmanship with oriental aesthetics, making use of unique combinations of materials and colors.

REAL JEWELRY AND REAL JOY

In his 2011 book Luxurious Design: My Way of Designing Jewelry, Jin Ren (figure 18) shares the words he lives by: “If you want a nicely designed ring, come visit me.” If the whole luxury market is an ivory tower, he believes that natural gemstone jewelry is the top of that tower and design is its structure and soul. The ring is one of the most common jewelry items but also the hardest to design, according to Ren. He considers his work in ring design the major accomplishment of his career. One of the most famous jewelry designers in China, he is also a founder of the School of Gemology at China University of Geosciences in Beijing and author of the first Chinese jewelry design textbook.

With a PhD in geology, Ren never expected that one day he would co-host an haute couture show in Paris with world-class fashion designer Laurence Xu. When asked about his design education, Ren confesses that he barely had any. His career as a designer began purely by chance, starting just as the Chinese gem and jewelry industry boomed in the 1990s. At the time, he was a professor in the country’s only gemological program. The turning point came in 1993, when a magazine invited him to write about jewelry fashion trends. His reputation grew from there, eventually providing a foundation for his own brand, RJ (Ren, 2011).

Along with his name, the RJ brand stands for “Real Jewelry and Real Joy.” He considers jewelry design a matter of controlling shape, size, color, and dynamics, combined with a strong emphasis on culture (Ren, 2011). His designs combine traditional and contemporary concepts, encompassing mechanical design techniques and often reflecting a storyline that connects one piece to another (figure 19).

Ren and his friend Laurence Xu often get together to discuss fashion trends and design ideas. Because they share common interests, Xu invited Ren to be the jewelry designer for his collection at Paris Haute Couture in 2013. Xu’s majestic garments and Ren’s matched jewelry suites reflect their shared identity and heritage (figure 20).

Ren says his themes come from outings with family and friends, where he is inspired by people, architecture, movies, and ancient fairy tales (Ren, 2011). His jewelry suite “Journey to the West” is based fairy tale that is considered one of the four great masterpieces of Chinese literature. Baroque pearls represent the four main characters on their expedition to the West, including the famous Monkey King (figure 21). Their adventures are treasured childhood memories for almost every Chinese person.

REVIVAL OF GOLD-JADE CULTURE

Jade-mounted gold jewelry has a long history in Chinese culture, where gold represents splendor and jade symbolizes elegance. Chinese people use the relationship between gold and jade to symbolize a happy marriage. For political and economic reasons, the market for this type of jewelry was very limited for many years (“Revival of gold-jade culture…,” 2014). After the jade-mounted 2008 Olympic medals were announced, the market sensed an opportunity to revive what is known as the gold-jade culture.

Shanghai jewelry designer Kaka Zhang’s interests and talents encompass art, science, and business (figure 22). She designs for the high-end, mid-range, and commercial markets, using designs and jadeite qualities to suit each market level. When she was three, her father taught her painting. Her high school and university studies included science and technology as well as gemology, leading her to a career in jewelry design and e-commerce.

Ninety percent of Zhang’s business is on the Internet, where she has a loyal and enthusiastic following. She operates her design studio and website from her home. Her jewelry is manufactured in Shenzhen, where skilled master jewelers turn her designs into finished pieces.

When Kaka Zhang purchased her first piece of jadeite jewelry as an adolescent, she never expected to become a designer in her own right. Along with the highly desirable imperial jadeite, Zhang uses colorless transparent jadeite, which has gained popularity among young female consumers in the past several years.

Most of Kaka Zhang’s design inspirations come from nature, also a major theme of traditional Chinese paintings (figure 23). She takes advantage of various colors and patterns and is often inspired by the jadeite carving itself. If its shape reminds her of something she has seen or heard—an old saying, a poem, a scene, or a painting—she bases her design on that theme (figures 24 and 25).

Jadeite is most often available as a carving whose beauty has been interpreted and revealed by the carver. The designer must consider the carving and envision the form or theme it will take. Although the gem cannot be altered, the composition may be enhanced by precious metal craftsmanship and other elements to express the theme in the designer’s inimitable style.

Zhang believes that to achieve success, she must educate her customers about jewelry design, materials, and manufacturing. Her dream is to establish a private jewelry club where she can create a relaxed environment and connect with each customer.

THE FUTURE

Over the past decade, Chinese jewelry designers have made great strides in matching the rapid growth of the domestic gem and jewelry market. Many are now well-known internationally. As Chinese designers continue to gain recognition, many more jewelry professionals will consider a future in design.

Native designers have come to understand that they must take advantage of their common cultural background, drawing from the heritage of time-honored craftsmanship and respect for the Chinese philosophical system. In the luxury market of the future, uniqueness will surpass high value (Yang, 2014).

Haute couture has a long history in China, though it was once limited to the royal family and the highest social classes. The high-end design market has seen more progress than other market sectors in the past decade. Now all top brands—and even some independent designers and small-scale stores—offer high-end custom design services. Designers now focus more on catering to the mainstream commercial jewelry market by learning from the Western world while maintaining many of their valued traditions. Leading jewelry enterprises are improving commercial jewelry design, hopefully resulting in more innovation in the near future. In 2013 and 2014, Rio Tinto launched a series of commercial lines of its Argyle diamond jewelry in China. Instead of marketing the diamonds themselves, Rio Tinto featured their commercial line designers in promotions through multiple media channels. The majority of them were young Chinese designers.

Chinese designers, especially large brands, are also making a global impact in the high-end jewelry market. Two recent examples are Chow Tai Fook Jewellery Group’s purchase of the U.S. diamond company Hearts on Fire and French luxury retailer Kering’s acquisition of Chinese jewelry house Qeelin. While Western brands have typically dominated the market, Chinese brands have gained an international foothold through their distinctive design, cultural connotations, and fine craftsmanship. The influence of the “Chinese soul” goes both ways.