Master Diamond Cutter Harvey Lieberman

For half a century, Harvey Lieberman has perfected the subtle art of cutting colored diamonds and bringing out their vivid hues and tones. Lieberman, nearing retirement, has sat at the same cutting bench (formerly his father’s bench) for 35 years in the renowned William Goldberg diamond cutting factory (figure 1). Goldberg (1925–2003) was a legend in his own right, often hailed as the father of New York’s Diamond District.

Lieberman is part of an elite community at the Goldberg cutting factory. Any given week might find Mutty Bornstein, Willy Lopez, Shmiel Wurzberger, or Eliezer Gottlieb at work. Each is a master cutter of both colorless and colored diamonds. Their camaraderie and shared passion for the craft make the factory a thriving hub of expertise and collaboration.

Lieberman graduated from Queens College in New York with a theater arts degree in 1974. He planned to wait tables, audition, and chase that big break. (Lieberman still does some occasional acting in off-Broadway productions.) But his father, being practical, told him, “Let me at least teach you a trade.” And with that, Lieberman apprenticed with his father, a master cutter on West 47th Street, learning the intricacies of cutting colorless diamonds.

His introduction to the craft at age 24 was cutting macles (twinned diamonds). Lieberman struggled with these uncooperative diamonds, whose crystal structures are knotted, watching as they ruined one cutting wheel after another. It was difficult, frustrating work. After nearly a year, he quit. He spent the next two years traveling, trying to sell gold and diamonds to jewelers, but it was not his calling. After two years of false starts, Lieberman returned to his father’s side, ready to give diamond cutting another shot. This time, though, he was armed with a better attitude and much more patience.

When his father became the foreman at Goldberg’s cutting factory, he brought Harvey along. The senior Lieberman did more than just cut and polish; he traveled to London, granted the rare privilege of attending De Beers sights. These were exclusive events where only a handful of companies could purchase rough diamonds directly from De Beers. Harvey joined him and had a front-row seat to the inner workings of the diamond industry, from the raw power of uncut gems to the dazzling brilliance of a perfectly cut stone. This became his world.

Everything changed when Lieberman first laid eyes on colored diamonds brought to him by his uncle, who had worked with the renowned Stanley Doppelt and Louis Glick. Doppelt and Glick would take in the yellow rough, painstakingly cutting it into smaller pieces to downplay the color. But his uncle had a different vision. He began cutting to maximize the color, pioneering a new market for vibrant yellow diamonds. This was Lieberman’s introduction to the magic of amplifying color through cutting.

Initially it was trial and error, and each stone was a new test—especially regarding the delicate pinks. One prominent dealer who sourced pink diamonds from Argyle would bring them to Lieberman to bring out the color. With that, Lieberman embarked on a journey to unlock the full potential of colored diamonds. Improving the color grade from intense to vivid became a goal. One time, Lieberman received an Argyle 2.14 ct Fancy Deep pink. After cutting it, he ended up with a stone just under 2 carats that had transformed into a pure red. The value improved nearly tenfold.

Lieberman worked under his father for a while and then for Louis Glick, who sent him to a De Beers sight and tenders in Africa (where non–De Beers mines sell rough diamonds, some in remote armed compounds). He was then assigned to start a factory in Africa. After a few years, he brought his family back to the U.S. and rejoined Goldberg, who had kept the same bench for Harvey after his father passed away.

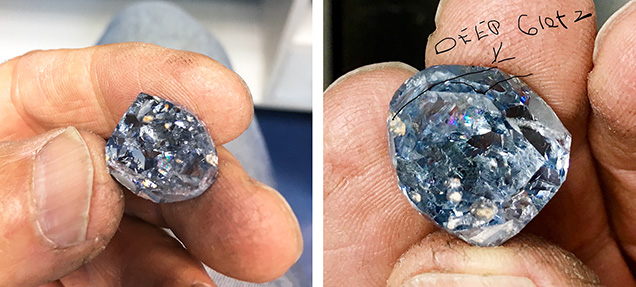

Lieberman has since worked with blues (figure 2 and figure 3, left), pinks (figure 3, right), reds, greens, and others. He has made color grades go from light to intense, all by changing how the diamond is cut. In the world of diamonds, color is everything. And improving that color is an art form few have mastered. Lieberman is one of the select few. With years of experience, he has transformed diamonds of all kinds, bringing out their hidden beauty. But sometimes, he looks at a diamond and has to tell the owner it cannot be improved. That candor makes his expertise especially valuable.

The works of Lieberman and his Goldberg factory collaborators have graced the halls of the Smithsonian (including the 5.1 ct Moussaieff Red diamond) and been highlighted at numerous auctions. One was a 1.92 ct Fancy red radiant cut diamond with VS2 clarity, the second most expensive red per carat at the time, sold at a Phillips New York auction. The Pumpkin diamond, a 5.54 ct Fancy Vivid orange cushion cut, was bought by Harry Winston at a Sotheby’s auction. These are just a few of their masterpieces.

This interview with Harvey Lieberman was captured on video (see below) as part of GIA’s Oral History Project to be used by future historians.