A Traditional Bombay Pearl Bunch

During the era when the maharajahs and maharanis ruled much of India, natural pearls were in great demand. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many merchants from the Middle East relocated to Bombay (now Mumbai) to benefit from this demand (R. Carter, Sea of Pearls, Arabian Publishing, London, 2012, pp. 169–175). Thus, it is no surprise that India has been a significant center of pearl manufacturing, processing, and trading for centuries. To showcase their high-quality pearls, traders and artisans in Bombay would sort the pearls, string them with silk threads, and tie them together at both ends using decorative metallic cords of various colors. These bunches were in great demand in the heyday of the natural pearl market and were sold as “Bombay bunches” (M. Manutchehr-Danai, Dictionary of Gems and Gemology, Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg, 2008, p. 101).

Recently, GIA’s Mumbai laboratory had the opportunity to examine an 80-year-old Bombay bunch inherited by one of the city’s established pearl families. The bunch consisted of 553 light cream round and near-round drilled pearls, strung in nine hanks, each containing four strands, with the exception of one hank with seven strands. The hanks were tied at both ends with white metal wires, together with silver and blue cords and tassels (figure 1). The pearls ranged from 3.83 to 5.72 mm, and the total weight of the bunch was approximately 80.51 g. The owner stated that the total weight of the pearls was approximately 130 chow (equivalent to 331.8 ct or 66.35 g). Chow is a system of converting weight into volume (The Pearl Blue Book, CIBJO, 2020).

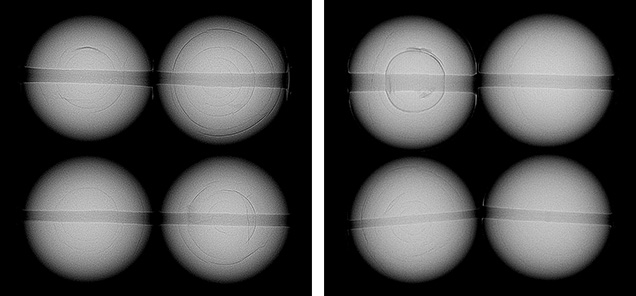

The strung pearls were perfectly matched in color and exhibited smooth surfaces with high luster. When viewed under 40× magnification, they all exhibited typical nacreous overlapping aragonite platelets. Their internal structures were examined by real-time microradiography. The majority revealed fine growth arcs and concentric ringed structures, while others revealed tight or minimal structures, some with small faint cores or light organic-rich cores (figure 2). It was evident that these were natural pearls from Pinctada-species mollusks, as their internal structures were very similar to those observed in Pinctada radiata pearls from the Arabian (Persian) Gulf when compared to GIA’s research database.

All pearls showed an inert reaction when exposed to optical X-ray fluorescence analysis. Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry on a few samples revealed manganese values ranging from below detection limits to 30.7 ppm and strontium values of 1215 to 1989 ppm, consistent with a saltwater growth environment. Raman analysis using 514 nm excitation was also carried out on the surface of selected pearls showing a doublet at 702/705 cm–1 as well as a peak at 1085 cm–1, indicative of aragonite. Very weak polyenic pigment-related peaks at 1130 and 1530 cm–1 were also observed in a few of the pearls, likely associated with their light cream coloration (A. Al-Alawi et al., “Saltwater cultured pearls from Pinctada radiata in Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates),” Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2020, pp. 164–179). The photoluminescence spectra under 514 nm excitation were also consistent with the Raman results and displayed high fluorescence together with the aragonite peaks, typical of most nacreous pearls. When exposed to long-wave ultraviolet light, the pearls showed a moderate blue reaction.

Historically, Bombay bunches were known to contain high-quality Pinctada radiata pearls fished from the Arabian (Persian) Gulf, commonly referred to as “Basra pearls” in the trade. Records indicate that the proportion of round pearls found in each natural pearl harvest today is less than 5% (H. Bari and D. Lam, Pearls, Skira, Milan, 2010, p. 43). Natural pearls are rare to find, and it can take decades to match a round pair of similar size, color, and luster. Encountering Bombay bunches in today’s market is a rarity, and it was a great opportunity for GIA Mumbai to examine such an interesting and memorable pearl submission.