Blackish Green Omphacite Jade from Guatemala

In recent years, a new kind of Guatemalan jade has entered the Chinese jewelry market, where it is called yongchuliao fei cui (or yongchuliao for short). Prior to the availability of yongchuliao, Chinese consumers had a negative impression of Guatemalan material and preferred Burmese jade. However, the recent emergence of this new high-quality blackish green jade has attracted the attention of Chinese buyers.

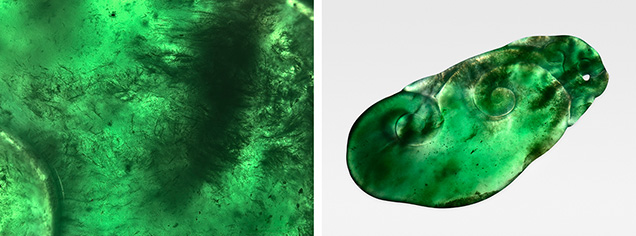

The authors recently tested a rough stone and a carved pendant of yongchuliao (figure 1). Under reflected light, these samples appeared blackish green with a greasy luster similar to Burmese inky black jade. The rough stone was opaque and had numerous fine white inclusions measuring approximately 300 μm in diameter on its surface. The carved sample was bright green with coarse texture and medium transparency under transmitted light (figure 2). The rough and carved samples had a refractive index of 1.67 and specific gravities of 3.342 and 3.332, respectively. These gemological characteristics are consistent with both jadeite-type jade and omphacite-type jade.

Qualitative analysis using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry revealed magnesium, aluminum, silicon, calcium, chromium, manganese, and iron, among other elements. It should be noted that the ideal chemical formula of jadeite is NaAlSi2O6 and that of omphacite is (Ca,Na)(Mg,Fe,Al)Si2O6 (S.F. McClure, “The jadeite/omphacite nomenclature question,” GIA Research News, April 12, 2012). Jadeite and omphacite can form a complete solid solution. The occurrence of calcium, magnesium, and other elements implies that the mineral composition of yongchuliao is not pure jadeite.

Raman shifts at 681, 514, 411, 378, 340, and 209 cm–1 were consistent with those of omphacite (figure 3). The Raman spectra of fibrous inclusions in the carved sample also matched those of omphacite rather than jadeite. The strongest Raman shift at 681 cm–1 was attributed to the symmetrical Si-O-Si stretching vibration (B. Xing et al., “Locality determination of inky black omphacite jades from Myanmar and Guatemala by nondestructive analysis,” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, Vol. 53, No. 11, 2022, pp. 2009–2018). Raman spectroscopy was used to compare the samples’ mineral composition against the RRUFF database (B. Lafuente et al., https://rruff.info/about/downloads/HMC1-30.pdf), revealing that yongchuliao material consists almost entirely of omphacite. The fine white inclusions distributed evenly in the rough sample were coincident with titanite (figure 3). In addition, some of the sample was ground into powder for X-ray diffraction analysis to obtain the mineral composition of the whole rock. The results showed an omphacite content of about 98.49% (with a 5% margin of error), and the rest was magnesian calcite. The results from Fourier-transform infrared absorption spectroscopy were consistent with the Raman spectra, identifying the main mineral composition of the samples as omphacite.

A double-sided polished piece was cut from the rough sample for testing. Its ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) absorption spectrum (figure 4) showed an absorption peak at 437 nm, indicating the presence of Fe3+. Absorption peaks at 637, 657, and 688 nm were also observed and attributed to Cr3+ (G.R. Rossman, “Color in gems: The new technologies,” Summer 1981 G&G, pp. 61–62).

Based on testing, both samples were omphacite-type jade containing titanite inclusions. Since almost all of the yongchuliao we have observed exhibited nearly the same colors and textures as these samples, it is likely that other yongchuliao may also have similar mineral compositions.