Synthetic Moissanite with Fraudulent GIA Inscription

GIA Johannesburg recently received a 1.02 ct round brilliant (figure 1) for a Diamond Grading report. Standard testing showed it was not a diamond, and subsequent spectroscopic and gemological analysis proved it to be synthetic moissanite. We often encounter simulants submitted for diamond grading, and they are easily detected through the standard grading process. This near-colorless synthetic moissanite was noteworthy because it had a fraudulent GIA inscription. GIA checks all stones with a preexisting inscription, and this one was obviously not inscribed by GIA. The report number does belong to an E-color natural diamond graded in 2019 with the same weight. But because of the dissimilar SGs of diamond and moissanite (3.52 and 3.22, respectively), their measurements were quite different.

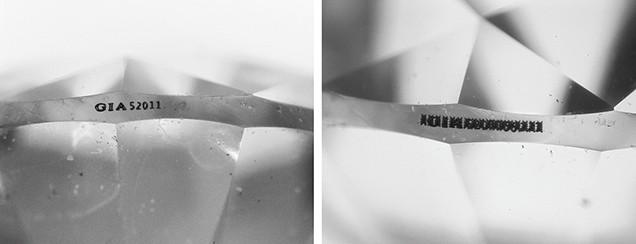

Furthermore, the fraudulent inscription (figure 2, left) was distinctly different from GIA’s standard inscription font. GIA’s standard practice in such cases is to superimpose characters to obscure the original inscription (figure 2, right). The clarity would have been equivalent to VVS2 (if such clarity grades were assigned to synthetic moissanite), while the clarity of the graded natural diamond was VVS1. The synthetic moissanite did not have any distinguishing inclusions, but it did show obvious double refraction in the microscope. Both IR absorption and Raman spectra confirmed the identification as synthetic moissanite.

In recent years, GIA has encountered similar instances of fraud. One was a synthetic moissanite that had been fashioned to resemble a natural rough diamond octahedron (Winter 2017 Lab Notes, pp. 462–463). That same year, an HPHT laboratory-grown diamond was submitted with a fraudulent inscription corresponding to a natural diamond (Fall 2017 Lab Notes, p. 366). However, this is our first instance of a fraudulent inscription on a diamond simulant.

Synthetic moissanite (SiC) is sometimes mistaken for diamond because some of its properties approach those of diamond, namely hardness and thermal conductivity (a trait measured in some instruments to distinguish diamond from many other simulants). However, several other properties are quite different from diamond, such as a much higher dispersion (leading to more obvious fire) and double refraction. Nevertheless, the possibility exists that a consumer could purchase this simulant thinking it was a natural diamond, especially with a deliberately misleading inscription. In this case, careful examination protected the consumer against such attempted fraud.

Authors’ note: Since the writing of this lab note, GIA Johannesburg has received and identified two more synthetic moissanites with fraudulent GIA inscriptions. They were handled in a similar manner.