Sri Lanka: Expedition to the Island of Jewels

ABSTRACT

In February 2014, the authors explored Sri Lanka’s entire mine-to-market gemstone and jewelry industry. The team visited numerous mining, cutting, trading, jewelry manufacturing, and retail centers representing each sector and witnessed a dynamic blend of traditional and increasingly modern practices. Centuries of tradition as a colored gemstone mining, trading, and cutting source now converge with the technologies, skill sets, and strategies of today’s global market.

INTRODUCTION

Sri Lanka is one of the meccas of gemology. Few sources, especially among active localities, can match its rich history as a gem producer and trade center. As Sri Lanka takes its place in today’s gem and jewelry industry, the gemologist can observe a combination of traditional methods and modern technologies as well as new business strategies for a highly competitive market.

What appear to be primitive practices are often highly efficient and well suited to the task. While most of the mining enterprises are small operations using simple hand tools, these allow for continuous mining, employ a large workforce, and are less damaging to the environment (figure 1). Cutting is another sector where traditional techniques still prevail, providing excellent initial orientation of the rough crystal for maximum face-up color and weight retention. At the same time, highly skilled recutting in Sri Lanka is achieving international market standards of proportions, symmetry, and brightness (figure 2). Fine precision cutting to tight tolerances on modern lapidary equipment is being applied to calibrated goods that meet the strictest requirements, including those of the watch industry.

While the small shops rely on jewelry manufacturing techniques such as hand-blown soldering, modern factories use lost-wax and casting as well as die-striking. Gem trading has evolved, partly due to more trade-friendly import and export regulations, making Sri Lankan buyers more competitive globally. The retail industry continues to find a large domestic market for traditional 22K gold jewelry while expanding to meet the diverse tastes of younger Sri Lankans and tourists.

SRI LANKA

Sri Lanka is a large island in the Indian Ocean, just off the southern tip of India. It measures 65,610 square kilometers (40,768 square miles), with 1,340 kilometers (832 miles) of coastline. In the southwest, where most of the gemstone mining takes place, the monsoon season lasts from June to October. Sri Lanka is located in the path of major trade routes in the Indian Ocean, an advantage that helped establish it as one of the world’s most important gem sources.

In addition to gemstones, Sri Lanka has natural resources of limestone, graphite, mineral sands, phosphates, clay, and hydroelectric power. The country is also known for its tea, spices, rubber, and textiles. Of the total workforce, 42.4% are employed in the service sector, 31.8% in agriculture, and 25.8% in industry, which includes mining and manufacturing (CIA World Fact Book, 2014). The tourist industry is expected to see strong growth, although the existing infrastructure may struggle to accommodate a large influx of visitors to such attractions as the ruins at Sigiriya, a UNESCO World Heritage site (figure 3).

Sri Lanka’s economy has experienced strong growth since 2009, which marked the end of a 26-year civil war that long plagued economic development. The country’s population of nearly 22 million encompasses different ethnicities and religions that are reflected in the styles of jewelry manufactured and sold domestically. The population is 73.8% Sinhalese, 7.2% Sri Lankan Moor, 4.6% Indian Tamil, and 3.9% Sri Lankan Tamil (with 10% unspecified). Buddhists account for 69.1% of the population, Muslims 7.6%, Hindus 7.1%, and Christians 6.2% (CIA World Fact Book, 2014). While Muslims and Hindus represent a distinct minority, they have a rich jewelry tradition, and the authors witnessed the importance of their buying power in the retail industry.

GEM TRADE HISTORY

Gemstone use in Sri Lanka dates back at least 2,000 years. The gem-laden island was referred to in Sanskrit as Ratna Dweepa, meaning “Island of Jewels” (Hughes, 2014). Early Arab traders called it Serendib, which is the origin of the word “serendipity.” Known until 1972 as Ceylon, it has a rich history as a source of economically important gemstones, particularly sapphire (figure 4) and cat’s-eye chrysoberyl.

James Emerson Tennent, an administrator of British Ceylon from 1846 to 1850, noted that the Mahavamsa (The Great Chronicle of Ceylon) mentions a gem-encrusted throne owned by a Naga king in 543 BC, when the earliest accounts of the island were written (Hughes, 1997). The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote that ambassadors from Taprobane, as Sri Lanka was known at the time, boasted of its fine gemstones during the reign of Emperor Claudius from 41 to 54 AD (Hughes, 1997). The Greek astronomer Ptolemy referred to the island’s beryl, sapphire, and gold in the second century AD (Hughes, 1997). Marco Polo traveled there in 1293 and noted the abundance of gems, including ruby, sapphire, topaz, amethyst, and garnet (Ariyaratna, 2013). The famous Arab explorer Ibn Battuta, visiting in the 14th century, wrote of the variety of precious stones he saw (Ariyaratna, 2013).

Between 500 and 1500 AD, during the rule of ancient and medieval Sinhala kings, the mining, possession, and commerce of precious stones was controlled by the monarch. Arab and Persian merchants purchased many fine gemstones. During the periods of European colonization—Portuguese (1505–1656), Dutch (1656–1796), and British (1796–1948)—gem commerce expanded beyond the royal family, as the Europeans were solely interested in trading and profit (Mahroof, 1997). European traders brought more of these goods to the West and furthered the island’s reputation as a source of gemstones and trade expertise.

During the 20th century, Sri Lanka’s standing as a premier gem trade center diminished. This was due to numerous factors: the emergence of other sources, a failure to adapt and master technology such as heat treatment and modern cutting, and government regulations that hindered the rapid growth enjoyed by Thailand and other countries. In the last two decades, Sri Lanka has overcome those setbacks and now has a dynamic, rapidly growing gem and jewelry industry.

Sri Lanka is best known for its large, exceptional sapphire and star corundum. Important stones reported to be from Sri Lanka include (Ariyaratna, 2013):

- the 466 ct Blue Giant of the Orient, supposedly mined from the Ratnapura area in 1907

- the 423 ct Logan blue sapphire (figure 5) and the 138 ct Rosser Reeves star ruby, both housed in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History

- the 400 ct Blue Belle of Asia, said to have been found in a paddy field in the Ratnapura district in 1926, and described as having the highly desirable “cornflower” blue color

- the 363 ct Star of Lanka, owned by the National Gem and Jewellery Authority

- the 850 ct Pride of Sri Lanka blue sapphire, found in Ratnapura in June 1998

- the 563 ct grayish blue Star of India, which was actually discovered in Sri Lanka and donated to the American Museum of Natural History in 1900 by J.P. Morgan

- the 12 ct blue sapphire in the engagement ring of Diana, Princess of Wales, which is now worn by the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton

THE EXPEDITION

The goal of this study was to document the entire Sri Lankan colored gemstone industry from mine to market. While many past articles have focused on geology and mining, we decided to cover the entire spectrum, including gem mining, import and export, cutting, treatment, jewelry manufacturing, and retail. We wanted to rely heavily on our own observations for all of the sectors. We sought direct communications with industry leaders and trade members. Through extensive travel and numerous visits to different operations and businesses, we assembled the whole picture. Hundreds of hours of video footage and interviews and more than 7,000 photos documented all aspects of the industry in Sri Lanka.

Our first stop was at the offices of Sapphire Capital Group, where we saw Sri Lankan dealers serving as expert consultants for foreign buyers. For an entire day, we watched a buyer from New Zealand purchase parcel after parcel of sapphire and other gemstones from dealers his local contact had arranged (figure 6). As he chose his sapphires, the foreign buyer would consult the Sri Lankans on how the stones would recut. There we also captured the highly skilled recutting of sapphire and cat’s-eye chrysoberyl.

Over the next few days, we paid visits to wholesalers, retailers, and cutting facilities in Colombo. At Precision Lapidaries, we caught a glimpse of the modern Sri Lankan gemstone cutting industry, which emphasizes precision and quality. Our first trip outside of Colombo was to the weekend market at Beruwala, which was particularly busy (figure 7). We were able to see the art of street dealing in Sri Lanka, along with trading activity in the offices. We also interviewed traditional cutters and a specialist in the heat treatment of sapphire.

Our next stop was the famous gemstone market near Ratnapura, where the trading in the streets was even heavier than at Beruwala. We were allowed to visit numerous offices and traditional cutting and treatment facilities. After spending several hours at the market in Ratnapura, we explored pit-mining operations in the area.

At Balangoda we saw three mechanized mining operations and interviewed several miners. We were also able to watch a river mining operation. By this point in our trip, we had observed the three main types of gem recovery in Sri Lanka: (1) pit mining, including simple narrow pits with galleries and small open-cast operations, both worked by hand; (2) mechanized mining in open pits, incorporating backhoes or bulldozers for digging and sluices for washing; and (3) traditional river mining. In Elahera, another famous locality on our itinerary, we observed a mechanized operation and traditional pit mining.

Back in Colombo, we had three days to explore other cutting facilities, wholesalers and retailers, modern and traditional jewelry manufacturers, and the famous gem and jewelry hub of Sea Street.

GEM DEPOSITS

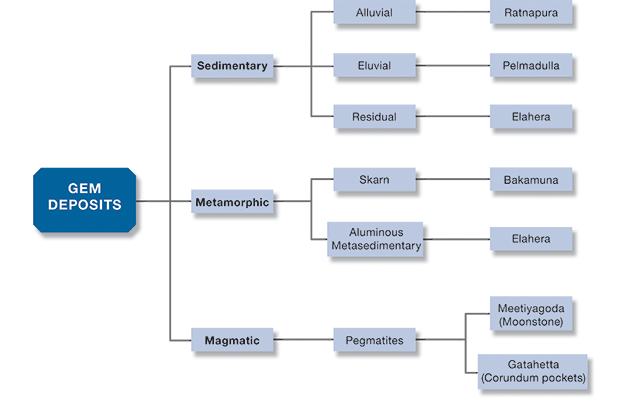

The classification of Sri Lanka’s gem deposits is summarized in figure 8. Most of the gem deposits are of sedimentary nature, though there are some primary deposits related to metamorphic and magmatic rock. Regional and/or contact metamorphism favored the formation of corundum and spinel by removing silica and water, transforming aluminum- and magnesium-bearing silicates into oxides. Pegmatites are the most important magmatic source of Sri Lankan gems, hosting beryl, tourmaline, corundum, and moonstone, among others. The most famous pegmatite is the moonstone deposit at Meetiyagoda, in southern Sri Lanka (Dissanayake and Chandrajith, 2003). Mendis et al. (1993) noted that many deposits are distributed along structural features such as faults, folds, and shear zones. Although these structures can influence the distribution of gem deposits, it remains unclear whether they are genetically related.

| Box A: A Related Earth History |

| The island of Sri Lanka has been blessed with some of the richest gem deposits on the planet. Metamorphism generated by a series of mountain-building events resulted in the gem wealth we see today. Before the well-known Pangaea, there were several supercontinents in Earth’s early history. The assembly and breakup cycles of these supercontinents are the engines that formed most of the world’s gem deposits (figure A-1), and some of these events are closely related to gem formation in Sri Lanka. Nearly nine-tenths of Sri Lanka is underlain by high-grade metamorphic rocks of Precambrian age. Neodymium and rubidium-strontium dating (see Milisenda et al., 1988; Kröner and Williams, 1993) indicate an age between 1,000 and 3,000 million years (Ma). The supercontinent Rodinia, the predecessor of Pangaea, assembled between 1300 and 900 Ma (Li et al., 2008), so the protolith of these high-grade metamorphic rocks must have been inherited from previous supercontinent cycles. McMenamin and McMenamin (1990) considered Rodinia the “mother” of all subsequent continents. More than 75% of the planet’s landmass at that time had clustered to form Rodinia, but gigantic size did not translate to stability for the supercontinent. Due to the thermal insulation caused by the giant landmass, the first breakup of Rodinia happened at about 750 Ma along the western margin of Laurentia. Rifting between Amazonia and the southeast margin of Laurentia started at about the same time (Li et al., 2008). While Rodinia was breaking up, the individual continents of Gondwanaland started to join together. Gondwanaland was assembled between 950 and 550 Ma (Kröner, 1991). Detrital zircon age distributions indicate that the global-scale Pan-African orogeny reached its peak between 800 and 600 Ma (Rino et al., 2008). This orogeny formed one of the longest mountain chains in Earth’s history: the Mozambique belt that extends from modern-day Mozambique to Ethiopia and Sudan and also covers most of Madagascar, the southern tip of India, Sri Lanka, and the eastern coast of Antarctica. This belt, a thrust-and-fold zone that marks the junction between East and West Gondwanaland, is also a mineral belt. Modern-day Sri Lanka occupied a central position in this belt. Uranium-lead geochronology shows that the zircons from Sri Lanka’s high-grade metamorphic rocks experienced significant Pb loss at 550 Ma, and new growth of zircon, monazite, rutile, and garnet occurred between 539 and 608 Ma (Kröner and Williams, 1993). These are the dates of the near-peak metamorphism that created the gemstones in this country. Figure A-1. The supercontinent Rodinia was formed 900 million years ago and started to break apart about 150 million years later. Some of its fragments reassembled to form Gondwanaland, which later became part of the supercontinent Pangaea. South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, Antarctica, and Australia were once connected in Gondwanaland. Adapted from Li et al. (2008) and Dissanayake and Chandrajith (1999).

|

Almost all of Sri Lanka’s sources are alluvial, containing rich concentrations of gem-bearing gravels called illam (figure 9). In addition to sapphires, a variety of other gems are recovered from the illam, including spinel, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, and moonstone. Very few important primary deposits have been found. One was discovered by accident during road construction in 2012 near the town of Kataragama (Dharmaratne et al., 2012; Pardieu et al., 2012). The sapphire find was highly valuable, estimated at US$100 million or higher, so the government auctioned off surrounding plots of land for mining. Although these small plots sold for the highest price ever recorded for gem mining licenses in Sri Lanka, no commercially valuable deposits were subsequently found. But a full geological study of the deposit has yet to be conducted, so the true potential of Kataragama is still unknown (V. Pardieu, pers. comm., 2014). Approximately 10 to 15 primary deposits of sapphire have been discovered over the last 20 years, all by accident (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014).

Most alluvial mining is done in areas with a history of gem production. There are many such areas in the central to southern part of the island. Due to the nature of alluvial mining deposits, concentrated gem-bearing gravels may be left behind. The alluvial gravels of Ratnapura and Elahera may contain samples from several types of primary deposits (Groat and Giuliani, 2014). Crystals found at or near the original source rocks can be beautifully shaped, such as those at Kataragama (figure 10). Crystals that have been transported longer distances, like specimens found in Ratnapura, are usually rounded pebbles (Zwaan, 1986).

Prospecting in Sri Lanka is rarely scientific. When evaluating an area, the traditional method is to drive a long steel rod into the ground (figure 11). The prospectors examine the end of the rod for scratches and marks from contact with quartz and corundum, and for gravel stuck to it. Some can even distinguish the sound it makes. This method may also help in determining the depth, composition, size, character, and color of the illam (Ariyaratna, 2013).

With more than 103 natural river basins covering 90% of the country’s landmass (Dissanayake and Chandrajith, 2003), there are numerous places for gemstones to be concentrated in gravels. Deposits of corundum and other gems are known to occur in the southern two-thirds of the island (Hughes, 1997). We visited the mining areas around Ratnapura, Balangoda, and Elahera. Although these are but a small percentage of Sri Lanka’s gem deposits, they gave a representative overview of mining operations throughout the country. All of these are secondary gravel deposits—we could not find any primary deposits being mined.

| Box B: Local Geology |

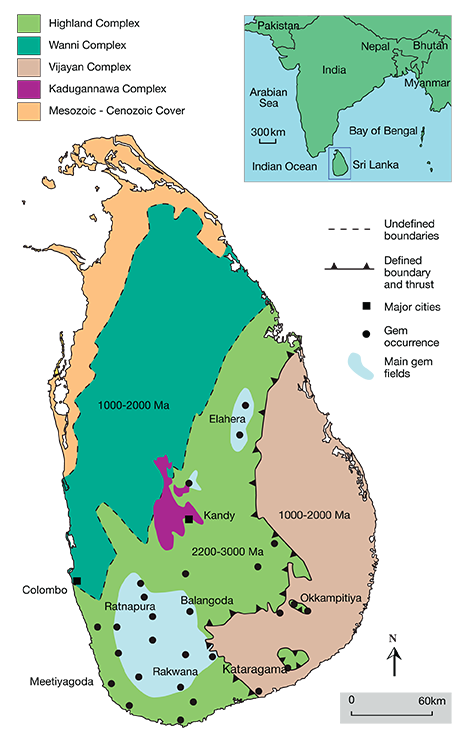

Consistent with the nomenclature suggested by Cooray (1994), the Precambrian basement of Sri Lanka can be divided into four units: the Highland Complex (HC), the Vijayan Complex (VC), the Wanni Complex (WC), and the Kadugannawa Complex (KC). Most of the gem deposits are located in the HC, which extends northeast to southwest (figure B-1). Found within the VC are klippes (island-like, isolated fragments of an overthrust rock layer) from the HC. One of Sri Lanka’s few primary sapphire mines was accidentally discovered in the Kataragama klippe (Pannipitiye et al., 2012). The Highland Complex contains high-grade metamorphic rocks such as pelitic gneisses, metaquartzite, marble, and charnockite gneiss (Cooray, 1994). Rocks in the HC have the highest grade of metamorphism (granulite facies), and the complex is younger than the VC to the east and south. The contact between these two complexes is a thrust fault dipping west and northwest, with the HC on top. This thrust fault is also a major tectonic boundary interpreted as a suture zone that marks the final junction between West and East Gondwanaland at approximately 550 Ma (Kröner, 1991). The VC is comprised of migmatites, granitic gneisses, granitoids, and scattered metasediments (Cooray, 1994). Lying west of the HC, the WC contains migmatites, gneisses, metasediments, and granitoids. The nature and exact position of the contact between the WC and HC is still not well defined (Cooray, 1994). The smaller KC is within the elongate synformal basins around Kandy. Hornblende and biotite-hornblende gneiss are the main rocks in the KC (Cooray, 1994). Other than these Precambrian basement units, the northern and northwestern coasts of the island are covered by Miocene limestone, Quaternary red beds and clastic sediments, and recent sediments (Dissanayake, 1986).

Figure B-1. Simplified geological map of Sri Lanka showing the main basement units and major gem deposits. Adapted from Sajeev and Osanai (2004) and Dissanayake and Chandrajith (1999).

|

MINING

While the modern mining industry promotes recovery by the fastest means possible, Sri Lanka embraces almost the opposite philosophy. Mining is done primarily by manual labor. The National Gem and Jewellery Authority (NGJA), the regulatory body that issues mining licenses, is very strict in its requirements for mechanized mining. This strategy keeps approximately 60,000 to 70,000 gem miners continuously employed (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014). The predecessor to the NGJA was the State Gem Corporation, which established regional offices and took control of mining licenses and guidelines in 1972. Its regulations for the gem industry supported legal mining operations (Dharmaratne, 2002).

Sri Lanka issued 6,565 gem mining licenses in 2013. Mining licenses must be renewed every year, and the number has steadily increased since 2009, when the NGJA granted about 4,000 of them. Many of these licenses are for small areas, half an acre to two acres. Each can accommodate two to four traditional pits, with about 7 to 10 miners per pit; deeper pits may accommodate 10 to 15 miners. This system has maintained a fairly constant number of active mines over the years.

Once a mining area is finished, the shaft or open pit must be filled in according to regulations enforced by the NGJA. These environmental measures pertain to loose gravel contaminating the surrounding water, damage to the landscape, and holes filled with stagnant water, a breeding ground for malaria-bearing mosquitos.

Pit Mining. In Sri Lanka, pit mining is the traditional mining method and by far the most widespread. More than 6,000 of the current licenses are for pit mines, compared to approximately 100 licenses for river mining and 10 for mechanized mining (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014). We witnessed numerous pit mining operations, all excellent demonstrations of the processes described to us by industry leaders. Miners are actually shareholders in such operations, receiving a small stipend and a percentage of the rough stone sales. As shareholders, they need little or no supervision. Several other people are involved in such a venture, including the landowner, the holder of the mining rights, and the person who supplies the pump to dewater the pit; they typically receive 20%, 10%, and 10% of the sales, respectively. The rest of the revenue is split among the financial stakeholders and the miners (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014).

To give an idea of scale, a standard pit mine in Sri Lanka consists of a two by four meter opening at the surface (figure 12). If the pits are deep and located in harder ground, the miners may choose smaller dimensions. The vertical shafts generally range from 5 to 25 meters deep.

The pits are created by first digging the opening to about a meter deep. The next step is making a wooden frame of timbers slightly taller than the depth of the pit. The miners place the first set of four timbers into the pit wall, which is grooved for a secure fit. Vertical struts of timber are wedged between the crossbeams. Branches and foliage help shore up the pit walls from water erosion, and timber braces are used in the center (figure 13). This process continues down the depth of the pit about every meter, until the miners reach the gem-bearing gravel. At this point they create horizontal crawl tunnels about 1.5 meters in height, called galleries, from the pit into the gem-bearing gravel. The length of these tunnels varies depending on the extent of the illam, but often reaches 5 to 10 meters.

The galleries extending from the pit are interconnected with other tunnels. This leaves some areas of illam that cannot be mined because they are needed for structural support. Buckets of gravel are either passed to the surface or hauled up by rope on a manual winch. Some pits have a wood and branch rooftop to shield the miners from the intense sunlight.

A pit with an opening wider than the traditional two by four meters is more like a very small open pit (also called an open cast), but it is still worked by manual labor. We witnessed some of these operations in Ratnapura and Elahera. Usually there were a half dozen people working in each pit. At least one miner at the bottom would shovel the illam into a woven bamboo basket held by another miner. That person would toss the basket to another miner, slightly higher up in the pit, who simultaneously tossed back an empty basket, like a perfectly harmonized juggling act. This process continued through several miners until the illam-filled basket reached the top, where it was dumped into a pile for washing. The accumulated mound of gem-bearing gravel could be covered with leafy branches, similar to those used to shore up the pit walls, to prevent rainwater from washing it away.

Pit mines with a standard two by four meter shaft opening follow a similar process for removing the illam, but often using a manually operated winch for hauling buckets to the surface (figure 14). In both examples, the illam is either washed in a nearby reservoir by simple panning or removed to a more sophisticated washing facility featuring a sluice. The sluices are often modified from Australian designs, as they are in other parts of the world. The washed gem-bearing gravel is called dullam (Zwaan, 1982), which is also the term for the smaller, lower-quality gems picked from washing baskets and usually given to miners to sell.

With around 6,500 mining licenses issued annually and around four or five pits in each mine, at any given time there could be 20,000–25,000 active pits in Sri Lanka. With extensive mining over the past 50 years, more than a million pits may have been dug altogether. Compared to many African mining countries, very few abandoned pits are left unfilled. This is because the NGJA collects a cash deposit upon issuing a mining license. If the mine owner fails to rehabilitate the land, the NGJA keeps the deposit for that purpose (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014).

Mechanized Mining. Only a limited number of mechanized mining licenses are issued in Sri Lanka each year. They may be granted if the concentration of gemstones is not high enough to make pit mining viable, or if there is a serious threat of illicit mining. To avoid large rushes of illicit miners to a rich discovery, the government may block access to the area or issue a mechanized mining license so the deposit can be mined quickly and legally (P.G.R. Dharmaratne, pers. comm., 2014).

Mechanized mining speeds the removal of overburden soil and the recovery of gem-bearing gravel for washing. Most mechanized mines in Sri Lanka are relatively small open-pit operations. Overburden soil sometimes contains dispersed gemstones, and it too may be washed. At mechanized operations, the illam is washed by sluices to keep up with the production (figure 15). Mechanized operations in Sri Lanka must also pay a deposit for the rehabilitation of the land.

While mechanized mining operations may use bulldozers, backhoes, excavators, front-loaders, trucks, and sluices for washing, they are still small-scale compared to those in other countries. The mechanized mining licenses are often issued by auction from the NGJA in blocks measuring 30 square meters.

We witnessed three mechanized mining operations near Balangoda. The largest was an open-pit operation about 60 meters deep on a property covering 50 acres (figure 16). It had four excavators, two washing sluices, and a few trucks. The excavators at the bottom of the pit loaded the trucks with gem-bearing gravel. The trucks climbed the roads on the pit benches back to the top to the washing operations. The four excavators worked in tandem to move the gravel up the pit until the highest one loaded the trucks.

With global weather changes, Sri Lankan miners are finding that the rainy seasons are no longer as predictable. This interferes with mining operations, whether traditional or mechanized. At the time of our trip, rainwater had filled many of the pits and needed to be pumped out before mining could resume. The pit at the largest mechanized operation we visited took more than a week to dewater.

River Mining. Although nowhere near as prevalent, river mining is also conducted in Sri Lanka. These areas may contain alluvial gem deposits where the river bends or otherwise slows down. The miners choose shallow waters and build a dam made of wood or rock where the stream slows, allowing the water to escape from one side of the dam but trapping the gravels.

Using metal blades attached to long wooden poles called mammoties, the miners dredge the gravel until they reach the illam (figure 17). Long pointed steel rods are used to loosen the illam, which is dragged up and washed by the rushing water. Once any visible gemstones are removed, the remaining gravel may be further washed.

We observed a river mining operation in Balangoda next to a tea plantation. There were four miners using mammoties to remove the illam, two miners washing gravels with baskets, and another removing larger rocks and building dams. Another miner would wade into the water to remove gravels and larger rocks. We did not see the use of mechanized or powered dredgers at any river mines.

CUTTING

Gemstone cutting is another area where the traditional meets the modern in Sri Lanka. Centuries of experience in cutting corundum and other colored gemstones continue alongside new technologies and business models. The time-honored art of reading rough and orienting stones is integrated with the global market’s growing demand for exact calibration, well-balanced proportions, and high-quality polish.

Our team observed several examples of traditional and modern cutting, as well as some of the highest-precision cutting of colored gemstones we have ever witnessed. Numerous interviews with members of the Sri Lankan cutting industry revealed the interwoven nuances of blending the past, present, and future. There is still a relevant place for old-style cutters and their expertise, even as innovative companies are thriving.

While Sri Lanka has seen some growth in diamond cutting, with 20 companies active in 2013—including De Beers sightholder Rosy Blue—most of the activity is focused on colored stones, particularly sapphire. The number of licensed cutting businesses has increased only slightly over the last five years, from 174 to 192, though today there are larger, more modern lapidary companies.

Traditional Cutting. While the West and Japan sometimes view traditional cutting in Sri Lanka as outdated and not up to modern global proportion and symmetry standards, one can still appreciate the craft. These cutters use a bow to power a vertical lap, often holding the stone by hand or with a handheld dop as they cut and polish (figure 18). They have a high degree of skill in orienting rough gemstones to achieve the best face-up color while retaining weight. Decades and even centuries of knowledge have been passed down on orienting sapphires and other gemstones such as cat’s-eye chrysoberyl. Of all the cutting steps for colored stones, orienting the rough to display the best color through the table requires the highest skill, especially with valuable rough where weight retention is foremost. For high-quality sapphires, this method is still preferred by Sri Lanka cutters, especially for preforming.

While blue sapphire often displays its best color through the c-axis, a skilled cutter can make slight angle adjustments to the table and still achieve a fine color with higher weight yield. If this is not done at the initial orientation, multiple recuts may be needed to get the right orientation of the table. With the orientation properly set, the recut produces a beautiful stone with minimum weight loss. For example, a 22 ct blue sapphire that is properly oriented for face-up color can be recut to close windows and optimize proportions and symmetry, while keeping the stone above 20 ct.

If the orientation or proportions of a blue sapphire cause a reduction of color, the stone’s value suffers accordingly. This is especially true for light- to medium-tone blue sapphires, where even a 5% to 10% reduction of color diminishes the value more than a 5% to 10% weight reduction.

Precision Cutting and Free Size Cutting. For Sri Lanka to become a leader in the colored stone trade, its cutting industry must meet the specific needs of the global market, where customers from different countries require a wide variety of cutting specifications and tolerances. In Sri Lanka, many fine-quality sapphires over one carat are cut as free sizes. The cutting is performed to minimize windowing and yield pleasing proportions and symmetry rather than exact calibrated measurements. This allows weight retention on more valuable material while creating a beautiful stone with high brilliance. This is essentially a cost decision. It is less expensive to adjust mountings from the standard 12 × 10, 10 × 8, and 9 × 7 mm sizes than to lose weight from valuable gem material. With larger fine-quality material, sizing considerations always give way to beauty and weight retention.

Even customers of calibrated sapphires have a range of tolerances. Some can accept a tolerance range as wide as 0.5 mm. For instance, sapphires cut to 7 × 5 mm sizes can vary up to 7.5 × 5.5 mm for some clients. Others have stricter tolerances, such as 0.2 mm, based on their jewelry manufacturing and mounting requirements. Some cutting companies offer tolerances of 0.1 mm or less (figure 19).

In Colombo, our team visited Precision Lapidaries and interviewed managing director Faiq Rehan. We also spoke with Saman K. Amarasena, vice chairman of the lapidary committee of the Sri Lanka Gem and Jewellery Association and owner of Swiss Cut Lapidary. On both occasions, we gained insights on the state of precision cutting in Sri Lanka.

Despite being a fifth-generation member of the gem industry, Rehan started Precision Lapidaries in 1990 with a business model that was unconventional for Sri Lanka. Rather than cutting only large stones and selling them individually, he specialized in bulk quantities of calibrated cuts, applying the precision standards he had learned years earlier while cutting diamonds. The new company soon received large orders for calibrated sapphires in 2 to 4 mm princess cuts from Japanese clients who constantly pushed for tighter precision and higher quality. In expanding his business, Rehan preferred to hire young people directly out of school and train them to cut sapphire to his exacting standards. This philosophy was unusual in Sri Lanka, where cutters often come from a long line of cutters with deeply ingrained procedures and standards.

As he entered the American market, Rehan found buyers wanting much larger quantities of stones cut at a much faster rate. They did not share the Japanese appreciation for precision measurements and higher quality of symmetry and polish. Rehan did not want to abandon his standards of precision and quality, however. He found that serving a high-quality niche market, rather than having a large inventory full of product similar to what was already available, allowed for constant inventory turnover.

Rehan believes that the high-end and commercial markets in the United States and elsewhere are moving toward stricter precision and cut quality, and he has expanded his business to fill this demand. Many others are doing the same, and this is changing how the world views the Sri Lankan cutting industry. China now requires very bright stones with no windows or dark areas, as well as excellent proportions and symmetry. Chinese demand for its massive jewelry manufacturing industry has helped fuel the growth of precision cutting in Sri Lanka.

The actual production model at Precision Lapidaries is also very different from many other cutting operations. Each cutter assumes full responsibility for a given stone instead of handing it off at different stages as in an assembly line. Some large-scale diamond cutting factories in India have also switched to this model to achieve higher quality standards through personal accountability (D. Pay, pers. comm., 2014). Using this model, Rehan treats his cutters more like partners, basing their compensation on both production and quality.

Each cutter has an individual glass-walled workstation to eliminate distractions. A cutter’s typical output, using an already preformed and calibrated 8 × 6 mm oval as a benchmark, is 140 to 180 stones per eight-hour workday. The stones are tracked throughout the process and entered into a database. There are several quality control checks at the calibration stage (which requires tolerances of 0.1 mm or less), the faceting stages, and the finished product stage. The company’s production manager noted that if any quality factors are not up to standards for calibration tolerance, facet symmetry, proportion variations, or polish, the stone is returned to the cutter with a repair order.

Another nontraditional practice at Precision Lapidaries is its use of detailed inventory and grading reports, the kind favored by large diamond cutting companies. While there was initial resistance, over time customers became comfortable with the information contained in these reports. Each one itemizes a parcel by shape, weight, cutting style, color, and other quality factors. Established customers can review the reports to make buying decisions and place orders, even through the Internet.

Swiss Cut Lapidary, which supplies the watch industry with colored gemstones, also stakes its reputation on precision and accuracy. The luxury watch industry requires very small stones cut with a high degree of precision, including very tight proportion tolerances for crown height, pavilion depth, and crown angle. Swiss Cut Lapidary cuts round faceted stones below 1 mm, and even down to 0.35 mm for ladies’ watches. At these sub-millimeter sizes, each faceted stone has eight crown facets and eight pavilion facets. By achieving zero tolerances to the hundredth of a millimeter, the company is able to meet the stringent demands of watch manufacturers. In finished rounds below one millimeter, the size difference between the starting rough and the faceted stone is very slight—for Amarasena, only 0.20 mm. In other words, for a round faceted stone of 0.50 mm, the rough can be as small as 0.70 mm.

To achieve this level of precision, Mr. Amarasena first learned traditional cutting by hand before working with mechanical lapidary equipment for Japanese clients. To further his skills, he traveled to Germany and Spain, where he cut a variety of colored gemstones using modern machines and techniques. Upon returning to Sri Lanka with high-precision Swiss-made equipment, Amarasena purchased mine-cut sapphires and recut them to global market standards. In Europe he had seen many Sri Lankan sapphires being recut, so he knew the exact requirements.

Amarasena also decided to shift his focus from recutting to unique designer cuts. At the annual Basel jewelry show, he noticed watches with small faceted gemstones set in the bezels. Back in Sri Lanka, he looked for small rough to use for cutting these stones. Rough chips were practically given to him because they were abundant and there was no real market for them. Amarasena faceted tiny precision stones from these chips in a wide variety of colors and tones, providing many options to watchmakers (figure 20). Although the rough costs slightly more today, its cost is minimal compared to the finished cut product. Micro-pave settings are another growing market for these precision-cut gemstones.

Recutting. In Sri Lanka, some sapphires are initially cut with what has been termed a mine cut or native cut (figure 21). While the proportions and symmetry are not up to modern gem industry standards, the cutters execute a high degree of skill in orienting the rough primarily for weight retention. These stones are considered advanced preforms that can be recut to market-friendly proportions and symmetry without substantial weight loss. The ideal color orientation has already been applied, so many Sri Lankan dealers simply have them recut to close windows and remove excess depth from the pavilions while making the shapes less bulky and more appealing.

The same holds true for gemstones sold decades ago that are reentering the global market. Special care must be taken with stones that have deep pavilions. While the market prefers pavilions that are not overly deep, any reduction of color will lower the value considerably (figure 22). If the recut involves more substantial weight loss, then the calculations become more complicated, and every case is unique. If a 2.08 ct stone is to be recut to 1.80 ct, the buyer must decide if too much of the premium would be lost below the 2 ct size.

These mine cuts from Sri Lanka were once exported to Thailand, the United States, and other countries to be recut to modern global standards. Eventually, Sri Lankan dealers realized they were missing out on a significant value-added service for their customers. Since the 1990s, they have provided that service, selling stones directly that meet the highest international cutting standards.

Besides facet-grade sapphire, our team witnessed the recutting of cat’s-eye chrysoberyl and star sapphire. The original mine cuts strongly favored weight retention over symmetry and placement of the cat’s-eye or the star. Recutting was needed to reposition these effects to the center of the cabochon and add symmetry. The recutting also made for a straighter cat’s-eye that moved more smoothly across the stone. While this involved some weight loss, it was often limited to a few points, and the final product would have significantly higher value on the global market. Japan was once the main market for cat’s-eye chrysoberyl from Sri Lanka, but that distinction now belongs to China.

TRADING

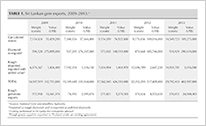

Much of Sri Lanka’s gemstone trading industry is centered on sapphire. Traditionally this was limited to goods of domestic origin, but today sapphires from around the world are brought to Sri Lanka for enhancement and cutting. Most import and export businesses are family-owned and go back several generations. For example, the fifth-generation Sapphire Capital Group has more than 100 family members involved in the industry. In 2013 there were 4,429 gem dealing companies in Sri Lanka, only a slight increase since 2009. Yet the quantity and value of exports has risen sharply over those five years (table 1).

Table 1 (PDF)

During the 1970s and 1980s, Thailand emerged as the undisputed leader in corundum trading. Its facilities began mastering the art of heat treatment, purchasing corundum rough from around the world. This included Sri Lankan geuda sapphire, which is translucent and has a desaturated, often grayish color. As the Thais discovered, heating this material gives it a transparent, highly saturated blue color. Sri Lankan buyers considered the geuda rough virtually worthless and were slow to capitalize on the use of heat treatment to turn it into a very valuable gemstone (Kuriyan, 1994).

Unlike their Thai counterparts, Sri Lankan buyers dealt primarily in domestically mined rough. Part of this had to do with the idea of preserving a national brand identity, but what really hindered them was a cumbersome import policy for rough. This changed in the mid-1990s when the government lifted import duties that had inhibited the purchase of corundum rough from other sources. Sri Lankan buyers have, in turn, established a strong presence in the marketplace, especially at global gem sources such as Madagascar and Mozambique. While the country’s industry still capitalizes on the brand identity of domestic gems, the trade is much more open to gems mined elsewhere.

The improvements in the Sri Lankan industry are timed perfectly to take advantage of the increased global demand for sapphire, particularly the Chinese colored stone market (“China becoming Sri Lanka’s top gem buyer...,” 2011). As an example of the rise in sapphire prices over the last few decades, untreated top-quality blue sapphires sold in Sri Lanka can reach US$15,000 to $20,000 per carat. Those are dealer to dealer prices. In 1969 similar stones would have sold for US$400 to $1,000 per carat—approximately $2,600 to $6,500 per carat, adjusted for inflation (N. Sammoon, pers. comm., 2014).

Local Mining Area and Street Markets. The first major street market we toured was in Beruwala, 60 km south of Colombo. The gem trading area of Beruwala is also known as China Fort, named for the Chinese merchants who arrived about 300 years ago. Most of the dealing occurs within a single block, where there is constant activity of dealers on the street. This market is open on Saturday from 6:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., or later if there is strong activity. During our visit, the market was also busy on Sunday. At any given time, over 5,000 dealers may be active on the street and in the hundred or so offices—the major dealers in Colombo have offices in Beruwala—offering rough sapphire from the mines of Sri Lanka, as well as Africa and other global sources. We witnessed a flurry of trading activity. Sri Lankan dealers often traded rough among themselves on the street (figure 23). Once word got out of a foreign buyer in a dealer’s office, other dealers would come by with their stones. There were also traditional Sri Lankan cutters and heat treatment facilities in Beruwala.

Just off the street was Emteem Gem Laboratory, where dealers could bring in stones for testing and identification. The demand for lab services has grown tremendously with the influx of foreign customers, especially Chinese buyers. One of the most sought-after services is the detection of heat treatment in corundum. This is also one of the most challenging identifications, especially if relatively low temperatures are used in the treatment. For corundum that has been subjected to very high temperatures, clients were advised to submit the stone to a foreign laboratory with more sophisticated instrumentation that could conclusively identify beryllium diffusion. About half of the stones submitted to the Emteem lab are believed to be of African origin (M.T.M. Haris, pers. comm., 2014).

We also stopped at the gem market in Ratnapura on the way to several nearby gem-mining operations. This market is active daily from 6:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Like Beruwala, this market was bustling on the streets and in dealer offices (figure 24). While the streets were crowded with dealers, the market was spread out over several streets, as opposed to the single block in Beruwala.

Ratnapura had numerous small traditional cutting operations. Like Beruwala, transactions were happening all over the street, particularly between Sri Lankan dealers. The market at Ratnapura is centered in one of the country’s major gem sources and offered plentiful rough from the nearby mines and other areas (figure 25). There was also an abundance of cut stones for sale. Some foreign buyers on the street dealt directly with local miners, but most transactions were between Sri Lankan miners and dealers. We saw the same dealers attending different markets.

Consulting for Foreign Buyers. One growing trend is for foreign buyers to work with Sri Lankan dealers to develop long-term supply chain management. The foreign dealers can arrange to have a variety of goods brought to their local contact’s office, allowing them to see much more inventory during a trip. The local dealer puts the word out to suppliers for the type of material required. Dealers bring their goods to the office for inspection by the foreign buyer. Prospective sellers are screened, making the transaction process more organized and less of a selling frenzy. Once the price is negotiated, the rest of the logistics—payment for the stones, export requirements, and shipping if required—are handled by the local contact, who receives a set commission from the seller.

Besides convenience, this arrangement offers several other benefits. The local contact can give expert advice on recutting, including the difference in carat weight and price per carat. They can also recommend an acceptable counteroffer and give an expert opinion on the nature of the material (figure 26). This system minimizes risk, as the local contact stands behind the goods they have brought to the foreign buyer. For extra assurance, they can have the stones checked by a gemologist before the buyer leaves the country. Colombo is a hub for such services, and this same expertise and assurance is sought by foreign buyers in Sri Lankan mining areas and street markets.

Imports and Exports. Sri Lanka’s import policies have been greatly simplified, making the process much easier and more cost-effective. For a US$200 charge, rough, preformed, and cut stones can be imported for cutting, recutting, and heat treatment. The flat rate charge is assessed regardless of quantity and value. As of 2013, foreign customers buying gemstones parcels valued at over US$200,000 are expedited through customs so they can board their flight with minimum processing. The export fee for these parcels is a flat rate of $1,500. Parcels valued below US$200,000 require about two hours to be processed by the NGJA for export (A. Iqbal, pers. comm., 2014).

Buying on the Secondary Market. Because Sri Lanka has been supplying sapphire, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, and other gemstones to the global market for so long, many dealers have decades of experience and an international clientele. Having maintained relationships with their customers, they know where to find important stones that were sold years before. They can contact their clients and act as brokers to resell the gemstones, making a substantial profit for both parties. As global wealth shifts toward China, previous customers in Japan and the West have become sources of fine-quality gemstones for this secondary market. These stones may be recut to more contemporary proportion and symmetry standards, and sapphires that were heated 30 years ago can be retreated using modern technology. A couple of decades ago, Sri Lankan dealers would attend exhibitions and trade shows in Japan and the United States to sell gemstones. Now some of them go to buy gemstones for recutting, heat treatment, and resale in the Chinese market.

HEAT TREATMENT

Sri Lanka is highly regarded for its heat treatment expertise (figure 27). Those who perform heat treatment, called burners, are known for their ability to get the finest blue color out of a sapphire. They typically use a two-part process, a combination of gas and electric furnaces. The second burn, in the electric furnace, refines the blue color, often achieving a much more valuable color. Some other countries that treat sapphire send their heated material to Sri Lanka for the second burn (A. Iqbal, pers. comm., 2014).

We visited one burner in Beruwala who heated blue sapphire from Sri Lanka and Madagascar in a gas furnace. The stones were heated to approximately 1600°C to 1700°C for four hours in an aluminum oxide crucible with a reducing atmosphere. For yellow Sri Lankan sapphires, the burner used an oxidizing atmosphere at approximately 1600°C for six hours. No compounds or fluxes were used in the crucible. The gas furnace is typically a Lakmini furnace, which has an alumina chamber covered in insulation and a stainless steel exterior, a water cooling system, two gas flow meters, two thermocouples and temperature indicators (digital or analog), a view hole, and an inlet top feed for an additional gas such as nitrogen or hydrogen (M. Hussain, pers. comm., 2014). An atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide is reported to work best for geuda sapphires, turning them transparent and blue (Kuriyan, 1994).

Clients typically bring mixed parcels of sapphires in different colors. The burner will divide the lot by color and type of sapphire and the desired result, and then advise the client of the different heating processes and what can be expected after treatment. Most stones brought to the burner are in the preform stage, so most of the inclusions that could cause damage are already cut away. Treatment in the gas furnace is almost always followed by heating in an electric oven to further improve the color (M. Hussain, pers. comm., 2014).

Expertise in heat treatment has also made Sri Lankans more competitive in buying rough from Africa and other sources. Some African blue sapphire, especially from Madagascar, is similar to Sri Lankan geuda material (F. Rehan, pers. comm., 2014). In value terms, the effect of modern heat treatment is tremendous. One Sri Lankan burner can reportedly take light blue sapphire with silk inclusions causing a foggy appearance, valued at US$300 per carat for a 10 ct stone, and heat it to a transparent fine blue color valued at US$2,000 per carat. This burner asks for one-third the value of the heated stone rather than a flat fee (N. Sammoon, pers. comm., 2014).

JEWELRY MANUFACTURING

As with gemstone cutting, there are both traditional and modern methods for jewelry manufacture. Both approaches are used in Sri Lanka, though some metals and styles are more suited to modern manufacturing. Mass-production techniques give some companies a competitive advantage by lowering costs. Jewelry made in Sri Lanka is targeted to the domestic retail market and to Sri Lankans living abroad. Manufacturing for export and for the emerging tourist industry is expected to grow.

Traditional 22K Gold Jewelry Manufacturing. The 22K gold jewelry manufactured in Sri Lanka is alloyed to have a slightly more reddish yellow color than similar goods from India, Singapore, Dubai, and Turkey. This is accomplished by using a slightly higher percentage of copper and a lower percentage of silver in the alloy.

In countless small workshops in Colombo and other areas of Sri Lanka, 22K gold jewelry is manufactured using time-honored and modern methods. We witnessed many of these shops in Colombo and during an extensive tour of the Sujitha Jewellery workshop on the famous hub of Sea Street. While small by global standards, this was one of the larger facilities we observed. They worked primarily with 22K gold and created traditional styles.

About a dozen jewelers were working in small rooms that made very efficient use of space. The jewelers sat on the floor as they fabricated by hand. Many of them were shirtless due to the heat. They bent and formed metal with pliers, filed, sawed, polished with flex shafts and traditional leather strips embedded with polishing compounds, and soldered. Most used jeweler’s torches, but one still preferred a blowpipe for soldering (figure 28). Equipment such as a hand-powered rolling mill and draw plate was used to make gold sheet and wire.

Modern Jewelry Manufacturing. In contrast to these traditional shops are modern facilities where technology has been embraced by the Sri Lankan jewelry manufacturing industry. Large-capacity vacuum casters imported from Italy can handle numerous waxes for mass production of both 22K gold jewelry and more contemporary pieces in 18K gold, white gold, platinum, or even silver. Other technologies such as casting diamonds in place, laser welding (instead of soldering), stamping or die striking, machining, and CAD/CAM—the methods used in manufacturing centers such as Italy, China, and India—have been adopted by progressive Sri Lankan jewelry manufacturers (figure 29).

We visited the modern factory of Wellawatta Nithyakalyani Jewellery in Colombo. The company manufactures jewelry primarily for its retail store and online business, which also serves overseas clients. The spacious facility handled all types of gold alloys, silver, and platinum, but a large part of the production consisted of 22K gold jewelry. While the factory incorporated methods such as lost-wax casting and die striking, there were also jewelers working on hand fabrication using traditional forming techniques, albeit at modern jeweler’s benches.

Besides traditional 22K gold jewelry for the domestic market, modern jewelry manufacturing is also being adopted by colored stone cutting and trading companies who are moving into finished jewelry. Customers from the United States and other developed markets are increasingly purchasing Sri Lankan jewelry with mounted colored stones (S. Ramesh Khanth, N. Seenivasagam, and N.S. Vasu, pers. comms., 2014). Jewelry that can be designed and custom-made to specifications is also manufactured in Sri Lanka.

One of Sri Lanka’s leading retailers and jewelry exporters, Wellawatta Nithyakalyani Jewellery is also one of its most progressive manufacturers. Along with mass-market 22K gold jewelry, they manufacture a full range of styles, including gemstone, synthetic gemstone, white gold, and platinum jewelry (figure 30). To safeguard against cross-contamination, tools such as files, polishing wheels, and burs are dedicated solely to platinum manufacturing.

In 1990, Wellawatta Nithyakalyani invested in a vacuum casting machine from Italy. The few other casting operations in existence used centrifugal casting. This machine gave the company an advantage in capacity, speed, and cost of producing jewelry for its retail store. In terms of consistency, vacuum casting lowered the weight variation of pieces from about 10% with hand fabrication to less than 1%. Today, the factory incorporates hand fabrication, wax carving, casting, stamping, and various settings such as prong, bead, pavé, and channel.

Wellawatta Nithyakalyani’s manufacturing methods are becoming more modernized and cost-effective. Even though hand fabrication costs remain relatively low in Sri Lanka, the competitive market and low margins for 22K jewelry have led to the widespread use of casting (figure 31) and stamping. Companies that manufacture and sell directly to retail customers have a distinct advantage, as they can eliminate distribution costs for this low-markup jewelry.

The company focuses its retail efforts on women and middle- to upper-class consumers in Colombo and its suburbs, where the country’s strongest jewelry market exists. The precious metal weight of its jewelry ranges from one gram to over 100 grams in a single piece, catering to a broad span of income. Wellawatta Nithyakalyani also manufactures and retails jewelry set with diamonds, colored gemstones, cubic zirconia, and crystal glass. This includes white precious metals, 18K gold, and traditional 22K gold used for weddings and as financial assets. The 22K gold wedding necklaces generally range from US$450 to $4,500.

Between its manufacturing and retail operations, the company staffs about 115 employees, representing a cross-section of Sri Lanka’s ethnic and religious groups. Its two full-time designers have degrees in architecture and are trained in jewelry design using CAD/CAM.

Most of Wellawatta Nithyakalyani’s export business is for mass-produced lines of jewelry sold in high volume. These are shipped to retailers in Canada, UK, Switzerland, Australia, and Dubai, where they are usually purchased by Sri Lankans living abroad. These expatriates also buy jewelry, especially diamond and gemstone merchandise, when they return to Sri Lanka for holidays. In addition, the company’s website offers an extensive line of jewelry directly to retail customers worldwide.

Another company that encompasses the manufacturing-to-retail value chain can be found on Sea Street, home of Ravi Jewellers. The company, founded in the 1960s by Ravi Samaranayake as a small traditional 22K gold jewelry retailer, has operated continuously for almost 50 years. Today, the firm is involved in jewelry manufacturing, creating jewelry of all styles sold directly to retail customers (figure 32).

With its modern manufacturing capability, Ravi Jewellers also sells wholesale to other retailers throughout Sri Lanka. This demonstrates another emerging trend where companies that cover the manufacturing-to-retail value chain sell wholesale to smaller domestic retailers. Their manufacturing division also allows them to provide an extensive custom design service to their retail clients and on the wholesale level to other retailers, a business model that creates a competitive advantage. In addition to being the Sri Lankan agent for Swarovski synthetic cubic zirconia, the company markets Italian alloys and serves as an official currency exchange to accommodate tourists. It has even ventured into selling gold bullion purchased in Dubai. For all its modernization and expansion of services, Ravi Jewellers remains a family business, typical of the Sri Lankan industry.

JEWELRY RETAIL

Sri Lanka has a thriving domestic retail jewelry industry. Its dynamics are different from those of Western jewelry markets and even elsewhere in Asia. Its retail industry is strongly influenced by jewelry’s role in Sri Lanka as an investment and hedge against economic uncertainty, the tradition of gold wedding jewelry, the preferences of religious groups, the tourist trade, the Western tendencies of younger consumers, and the lack of emphasis on gemstones in jewelry.

Jewelry as a Financial Asset. The use of gold jewelry for financial security is a tradition among many Sri Lankans. As one European gem dealer noted, they are more practical than Western jewelry buyers, who purchase luxury branded products as status symbols that lose most of their value immediately. When there is ample income, Sri Lankans typically buy gold jewelry that can be converted to cash during difficult economic times.

The pawn industry is a major component of the Sri Lankan economy, and most major banks issue loans with jewelry as collateral. The loans are based almost entirely on the commodity value of the gold, with heavier 22K pieces receiving the highest loan value. Some of the country’s major banks have anywhere from 17% to 40% of their lending portfolios concentrated in gold jewelry as collateral (A.P. Jayarajah, pers. comm., 2014). Many lower- to middle-class Sri Lankans use pawn shops for 22K gold jewelry loans, receiving instant cash for 75% to 80% of the gold value. Most of these pieces are heavy, from about 80 to 160 grams. Clients generally redeem their items within six months to a year and pay a slight interest charge. Men tend to pawn jewelry more than women (V. Rishanthan, pers. comm., 2014).

During the height of the gold market, when prices soared to more than US$1,700 an ounce, the lending industry became very competitive and pawn shops were offering around 90% of the gold value of jewelry. Many consumers did not redeem their jewelry at these loan values, and when the price of gold fell, the pawn shops lost substantial collateral value.

Wedding Jewelry. For most jewelers in Sri Lanka, the wedding business is arguably the most important. Although jewelry trends inevitably change, gold is an essential component of a Sri Lankan wedding. Jewelry is given to the bride and the groom, as well as the bridal party. Around 80% of this wedding jewelry is for the bride, though jewelry purchases for the groom are on the rise (V. Rishanthan, pers. comms., 2014). Traditional 22K gold jewelry remains the wedding jewelry of choice, and it is still used as a dowry in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lankans comprise many of the major religions: Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity. Each religion has its own style of jewelry, especially for weddings, with differences both subtle and obvious (A.P. Jayarajah and V. Rishanthan, pers. comms., 2014). Hindus tend to wear larger, heavier jewelry of a more Indian style, and designs are often based on what is popular in India (V. Rishanthan, pers. comm., 2014). In Hindu weddings, the bride is given substantial amounts of 22K gold jewelry, including a thick Thali necklace (often weighing between 80 and 250 grams) and longer chains, as well as bangle bracelets. The groom usually receives one simple ring. The bridesmaids and the groom’s mother and sisters also receive 22K gold jewelry, making Hindu weddings a major jewelry purchasing event in Sri Lanka.

Buddhists use both rings and necklaces for weddings, often with more floral and classic Sinhalese designs. Sinhalese Buddhists tend to choose lighter, more delicate designs than Hindus for weddings. Brides are presented with a ring, necklace, bangle, and matching earrings in their wedding sets, and the groom receives a gold ring. Still, most Buddhist weddings do not involve as much gold jewelry as Hindu weddings.

In addition to the Thali, Sri Lanka’s Christian community uses rings for the bride and groom. Whereas Hindu Thali necklaces often incorporate a square shape with a symbol of Vishnu inside, Christian Thali designs feature the Bible or a heart shape with a dove. Muslims tend to buy larger and heavier bangle bracelets than the Hindus, Buddhists, or Christians.

Sri Lankan retailers immediately know the ethnicity and religion of their customers by observing the jewelry they wear into the store. Of the more than 3,500 bangle bracelets in Wellawatta Nithyakalyani’s product lines, around 95% of these are 22K gold. This is the bracelet of choice in the Muslim community, whose women display their bangles stacked on the arm. Muslim brides also receive a Thali and a large chain, matching earrings, and engagement necklace. Grooms often prefer a white metal for their ring.

Expatriate and Tourist Trade. The strong tie between Sri Lankans and their jewelry is not confined to the island. Sri Lankans living abroad, many of whom left during the civil war, purchase traditional jewelry when returning to their native land. The month of August is especially busy for Sri Lankan retailers, as many expatriates living in Europe return for vacation (V. Rishanthan, pers. comm., 2014). They will plan out and purchase all the jewelry gifts needed for the entire year, such as weddings, birthdays, and other occasions. Again, most of them choose traditional 22K gold jewelry based on ethnic or religious heritage.

Since the end of the civil war in 2009, tourism has been growing. With over one million tourists in 2013 and an expected doubling of that figure in 2014, retailers noted a dramatic impact on sales. Many of these tourists are Sri Lankans living abroad, but retailers are seeing more European, Australian, American, and especially Chinese visitors. The country’s jewelry industry is working to brand Ceylon sapphires, which are sold in boutiques of major hotels (A. Iqbal, pers. comm., 2014). Retailers are reporting the positive effects of tourism on sapphire jewelry sales. Global awareness of Sri Lankan sapphires was also heightened in October 2010, when Great Britain’s Prince William gave Kate Middleton a Sri Lankan blue sapphire engagement ring—the same ring worn by his mother, Diana, Princess of Wales. According to officials from the NGJA and the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA), demand for Sri Lankan blue sapphires in engagement rings rose sharply in the West and in China.

Sea Street. One of the most important areas for Colombo’s jewelry trade is near the harbor on Sea Street. The Sea Street jewelry trade was started in the early 1900s by the Chettiar community, a Hindu caste originating in southern India. They are known as a mercantile class of businesspeople and bankers. The Chettiar merchants were involved in money lending, largely with jewelry as collateral. Over time, this led to the development of jewelry retail, wholesale, and manufacturing businesses on Sea Street. By the 1950s, the district had become the major jewelry hub of Sri Lanka, focusing on 22K gold. There are still Chettiar temples on Sea Street today, though much of the community has returned to India (V. Rishanthan, pers. comm., 2014).

While Sea Street remains the country’s jewelry hub, the rest of the country has seen significant retail and wholesale growth since the end of the civil war. Sea Street often supplies these new retailers with wholesale jewelry and manufacturing, or with specialized services such as stone setting, laser welding, and plating. In return, small local manufacturers throughout Sri Lanka supply finished jewelry to Sea Street retailers (V. Rishanthan, pers. comm., 2014).

Walking down the few blocks of Sea Street, you see hundreds of jewelry stores and pawn shops (figure 33). Closer examination reveals that some of the storefronts lead to complexes divided into 50 to 100 very small shops, some just 10 by 10 meters. Within these shops, jewelry is crafted using traditional methods. Much of the manufacturing on Sea Street consists of family businesses that continue from one generation to the next.

Gemstone Jewelry Market. While Sri Lanka is known all over the world as an abundant supplier of sapphire and other colored gemstones, the local market for gemstone jewelry is surprisingly weak. Much of the domestic demand is for 22K gold jewelry without gemstones.

Even more interesting is the Sri Lankan preference for synthetic cubic zirconia and crystal glass in jewelry. This is directly related to the custom of buying jewelry as much for financial security as for personal adornment. Sri Lankans can always go to a pawn shop or bank and receive a high percentage of the gold value in their jewelry as a loan. Once gemstones are added to the jewelry, it becomes more difficult to receive a loan value close to the cost of the piece. The gemstone value is not as liquid and cannot be assigned a market value for a loan.

As a low-cost alternative to add color and sparkle to their jewelry, many Sri Lankans opt for cubic zirconia and crystal glass (figure 34). For instance, a 22K gold bracelet set with CZ might cost US$500 at Wellawatta Nithyakalyani, compared to US$5,000 for a comparable bracelet set with good-quality natural diamonds. Unlike consumers in the West or Japan and China, Sri Lankans see little reason to spend the difference. For mass-market 22K gold jewelry, most consumers only allow the addition of gemstones up to 25% above the price of the gold. After that, there is price resistance. Sri Lankans are often willing to spend more on gemstones in 18K gold jewelry—approximately 40% above the gold value—and even more for platinum jewelry. But this custom is slowly changing, and the market for natural colored gemstones and diamonds set in jewelry is growing, especially among upper-income and young consumers.

Younger Consumers. V. Rishanthan, director of Ravi Jewellers, compared the buying preferences of his mother’s generation and his wife’s generation. His mother’s generation, composed of women in their sixties, prefers large sets of 22K gold jewelry and substantial pieces weighing 40 to 80 grams. These impressive sets are reserved for special occasions such as weddings, birthdays, and visits to the temple. The rest of the time, such jewelry is kept in a safe or other secure location. This generation also views jewelry as a commodity that can be readily pawned for cash.

Rishanthan’s wife, representing the younger generation of women in their twenties and thirties, prefers lighter jewelry, such as necklaces weighing around 8 to 10 grams. His wife may own ten lighter pendants while his mother may have only two much heavier pendants. Younger women are very aware of jewelry’s financial uses but want to wear it every day, in a variety of fashionable styles.

Another trend among younger Sri Lankans is to resell their jewelry back to a store within six months to a year to trade it in for a new style. So while younger consumers may be buying lighter jewelry, they are buying more pieces and constantly exchanging them for new styles, creating more opportunities for the Sri Lankan retail industry. These younger consumers pay close attention to design trends and up-and-coming designers (V. Rishanthan, R. Samaranayake, J. Sasikumaran, and Y.P. Sivakumar, pers. comms., 2014).

The younger generation is also far more open to other gold alloys such as 18K, and they are especially fond of white metals such as platinum, white gold, and silver. Still, the sentimental and investment aspects of 22K yellow gold jewelry are not lost on the new generation of Sri Lankan consumers. Younger men are buying more jewelry for themselves, and these still tend to be heavier pieces.

With their preference for modern designs, younger consumers also buy more jewelry with diamonds (especially smaller ones) and colored gemstones, usually set in white metal. Blue sapphire is quite popular. Synthetic cubic zirconia or crystal glass can also be used to achieve the desired color. As with yellow gold jewelry, these white metal pieces tend to be lightweight.

CONCLUSION

Our expedition to Sri Lanka took us through all sectors of the colored gemstone and jewelry industry. While other reports have tended to focus on mining or treatment, very few have tackled the entire scope of the Sri Lankan industry. Over the course of two weeks, we witnessed mining operations, traditional and modern cutting, trading, treatment, and retail. The resulting documentation revealed a very vibrant industry across all sectors and allowed us to construct a complete picture.

The changes over the last decade have been significant. Modernized cutting has allowed Sri Lanka to produce precision cuts of the highest caliber. Meanwhile, traditional cutting continues to incorporate centuries of experience orienting sapphire, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, and other colored stones for color and weight retention. Mining is still aggressively pursued but mostly by small-scale operations, helping to preserve the environment and gem resources so more Sri Lankans have more opportunities to strike it rich.

A wealth of trade expertise gives Sri Lanka a competitive advantage as it looks to expand its share of the global gem market. Many foreign buyers consult with local dealers on purchasing decisions and the potential benefits of recutting and heat treatment. Rough stones imported from other global sources fuel the value-added industries of cutting and treatment. With decades of trading experience and a global client list, Sri Lankan dealers know where to find important stones for the growing secondary market, particularly in China. Meanwhile, trade organizations such as the National Gem and Jewellery Association and the National Gem and Jewellery Authority are working on a bilateral trade agreement that could eliminate import tariffs on colored gemstones entering China from Sri Lanka (R. Kamil, pers. comm., 2014).

Jewelry manufacturing is another sector that incorporates both traditional and modern techniques. Most of the manufacturing is to satisfy consumer demand for 22K gold jewelry, as a wedding gift and as a financial asset, at home and in Sri Lankan communities around the world. Younger consumers are demanding contemporary styles, new metals and alloys, and a greater use of gemstones. A growing tourist industry is also influencing Sri Lankan jewelry manufacture.

With rapid economic development since the end of the civil war in 2009, the Sri Lankan gem and jewelry industry could see dramatic growth, albeit at a much smaller scale than in neighboring India. Some of this growth is already happening in the diamond jewelry market, which has long been hindered by consumers’ limited purchasing power and the tradition of pawning jewelry for the commodity value of the precious metals. It remains to be seen whether Sri Lankan demand for contemporary jewelry featuring diamonds, colored stones, and alternative precious metals will match the popularity of 22K gold jewelry (figure 35).

The island’s gem and jewelry industry displays remarkable vitality and ambition for growth. With the ICA Congress coming to Colombo in 2015, the influx of foreign buyers to the annual Facets Sri Lanka show, and a stronger presence at trade shows in China, the Sri Lankan industry is striving for greater international recognition.