The Museum of London’s Extraordinary Cheapside Hoard

ABSTRACT

An astonishing collection of jewels, discovered by chance in 1912 after centuries of concealment, is on display at the Museum of London. Nearly 500 pieces, including jewelry, loose gems, and functional items, offer a unique glimpse into the global trade and use of gems in the 1600s.

INTRODUCTION

Just over a century ago, in the summer of 1912, a workman’s pickaxe struck through the floor of an old tenement house in Cheapside, a commercial district near the renowned St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. A trio of adjoining houses there was scheduled for demolition.

In a brick-lined cellar under a chalk floor, the workman cleared the debris and saw what appeared to be a decayed wooden box or casket containing a hidden treasure of several hundred gleaming jewels (Museum of London, 1928). Shock and curiosity, perhaps mingled with apprehension and greed, must have overcome the man, though his own story is not recorded. In this dank, long-forgotten cellar, the gems spilled onto the muddy floor and experienced their first light of day after nearly 300 years of concealment.

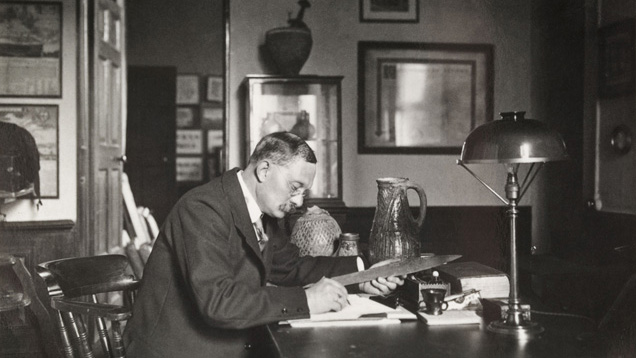

Fellow workmen are said to have immediately lined their pockets with the precious loot (figure 1; Forsyth, 2013), and much of the treasure buried in the cellar would have been lost to history were it not for a quirk of fate. An antiquities trader and pawnbroker named George Fabian Lawrence (1861–1939; figure 2) had established a shrewd arrangement with demolition workers. “Stony Jack,” as he was known, would pay them in cash or pints of beer for interesting finds made in the course of their work.

“I taught them that every scrap of metal, pottery, glass, or leather that has been lying under London may have a story to tell the archaeologist, and is worth saving,” Lawrence told the Daily Herald in 1937, toward the end of his life (Forsyth, 2003).

Lawrence’s success in antiquities, and his connections with the crews, paid off in 1912 when he became the inspector of excavations for the newly established London Museum. In the acquisition of archaeological finds, his accomplishments were remarkable—during his career he reportedly obtained 15,000 artifacts (Gosling, 1995), some of which were traded with museums around the world. In his first six months of employment with the museum, he sourced a total of 1,600 pieces (Macdonald, 1996).

The discovery on June 18, 1912, at the intersection of Cheapside and Friday streets (figure 3) was to become Lawrence’s most significant procurement. Over the ensuing weeks, parcels and handkerchiefs of jewelry from the hoard showed up at his office, and an astonishing collection began to accumulate. This treasure of mostly Elizabethan and Jacobean jewelry eventually constituted almost 500 pieces. Over the past century, items purportedly from the hoard have continued to trickle in. Mr. Lawrence’s own son presented two fancy-cut amethysts to museum officials in 1927. The stones were not documented, but it is quite possible they are the two amethysts pictured in figure 4.

After the discovery, pieces from the collection were held by three museums. The British Museum received 20 items in 1914, but the bulk of the treasure was split between the London Museum (now the Museum of London) and the Guildhall Museum in 1916 (H. Forsyth, pers. comm., 2013). Collectively the items became known as the Cheapside Hoard.

“The Guildhall Museum and the Museum of London came together in 1976, so we were really formed from two museums,” said Sharon Ament, director of the Museum of London. “Each of these museums had part of the Cheapside Hoard, and when they came together the hoard also came together.”

Most of the collection now resides permanently at the Museum of London. Its pieces continue to draw acclaim for their diversity, their enormous chronological range, and their relatively pristine condition. “This collection is unique in the world,” explained Hazel Forsyth, the museum’s senior curator of medieval and post-medieval collections. “It is the largest hoard of its kind, dating from the very late 16th to the early 17th century. Part of the reason why it’s so important is that jewelry tends to be broken up, refashioned, reworked, and so therefore doesn’t survive. Because this was buried and lay undisturbed for the better part of 300 years, it survived in the condition that it has. And it covers a huge spectrum of jewelry designs and types, but also gem material from many parts of the world, which really underlines London’s role in the international gem and jewelry trade in this period.”

For experts such as Forsyth, numerous unanswered questions surround this extraordinary find (figure 5). Who was the owner? Why did he hide the treasure, and when? Why was it never claimed? In seeking answers to those questions, close examination of the pieces elicits a form of intimacy with the onetime owner’s tastes and predilections, almost as if an image of the person could be conjured up through time. These found jewels also provide a snapshot of time and place, aligning themselves with historical events and filling gaps in our knowledge about how gems were cut and jewelry was fabricated and enjoyed in eras past (figure 6).

A picture of those eras emerges more clearly upon visiting London’s Victoria & Albert Museum and National Portrait Gallery. Both museums house magnificent portraits from the 16th through 18th centuries, often depicting European aristocracy wearing jewelry. In many cases they mirror the jewels found in the hoard and offer a tantalizing glimpse into how the jewels were actually used (figure 7).

In the summer of 2013, GIA was given the rare privilege of photographing several important items from the Cheapside Hoard at the Museum of London. This took place as the museum prepared for its first major exhibition of the collection, opening in October. The hoard was initially displayed in a small glass case in 1914, coinciding with the museum’s inauguration. In 1928, a richly illustrated catalogue describing some of the items was published. Over the years, some pieces have been shown in smaller exhibits. Now, nearly a century after the museum’s original exhibit, this new high-tech, interactive multimedia event features all of the known pieces from the hoard. This includes its wealth of rare enameled long chains, which were being painstakingly prepared for display at the time of our visit.

CONCEALMENT OF THE CHEAPSIDE HOARD

Scholars have concluded that the hoard was likely stashed for safekeeping by someone who expected to recover it at a later date. Forsyth said that newspaper accounts from 1914 describe a wooden box or casket. She and a colleague found possible evidence of soil contamination in some pieces, suggesting that the container disintegrated and its contents were gradually enveloped by the surrounding soil. “The other thing that is clear is how many pearls are missing,” Forsyth said. “I have worked out from the empty settings that there were probably 4,000 originally, or perhaps more in loose form, that rotted away in the soil.”

The location of the hoard is also telling. In the late 1500s, Cheapside and Friday streets in London’s West End were at the heart of a bustling jewelry manufacturing district, mostly concentrated along Goldsmith’s Row. By 1625, other businesses had entered the area, diminishing its luster. The properties where the hoard was located, tenement houses 30–32, were owned by the Goldsmiths’ Company. Because of subleasing and sub-subleasing to foreign workers, though, it is difficult to reconstruct the buildings’ inhabitants or determine who may have buried the hoard (Forsyth, 2002; Mitchell, 2013).

THEORIES ABOUT THE HOARD

Nonetheless, the condition and contents of the hoard offer potential insights. Forsyth describes it as a mixture of finished jewels of the latest fashion and design (figure 8), alongside other pieces that may have already been in circulation for centuries. Some of the stones had been removed from their settings, possibly for a jeweler to repair or repurpose. Forsyth believes the collection was most likely owned by a jeweler or syndicate of jewelers, but the extent and diversity of its contents also suggest the possibility that a wealthy collector or even a fence for stolen property could have owned it.

The hiding of the treasure occurred at a time before commercial banks were available to preserve valuables, so it may have been secreted away for safekeeping. “It could be that the jeweler did this regularly—that he had a hole in the floor where he kept his stock in trade,” Forsyth said. “It could also be that he was facing a calamity or emergency that required him to take desperate action. Possibly he planned to go abroad for a period of time. We know that almost 60% of the jeweler goldsmiths in London were immigrant craftsmen, and that they traveled.” Whatever the case, the owner of the hoard never reclaimed it.

Certainly it was a calamitous time in England. The outbreak of civil war in 1642 ultimately resulted in an overthrow of the monarchy and the execution of King Charles I in 1649. Unrest and political upheaval may have caused the hoard’s owner to hide his prized possessions, as many jewelers took up arms to fight. More uncertainty followed, including the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the return from exile of Charles II, son of the former king. Over the centuries, the bubonic plague had swept through Europe and Britain in waves, culminating in 1665–1666 with the Great Plague of London, which killed about 15% of the population. Those who had the means fled the city to avoid the deadly epidemic.

In 1666, a fire that started in a bakery spread quickly through the city. In less than three days it consumed more than 13,000 buildings, including St. Paul’s Cathedral, about a block away from the hoard. The Great Fire of London, as it came to be known, destroyed most of the city’s wooden structures, including those above the site of the treasure. Evidence of fire damage found during the Cheapside excavations led experts to conclude that the jewels were buried no later than 1666. It is unlikely that the owner of the hoard perished in the fire, as very few casualties were actually recorded.

Following the Great Fire of London and the rebuilding of the city, new structures were erected in the Cheapside district around 1670. This time, brick and mortar structures rose above the forgotten cellars, sealing the Cheapside Hoard for two and a half centuries.

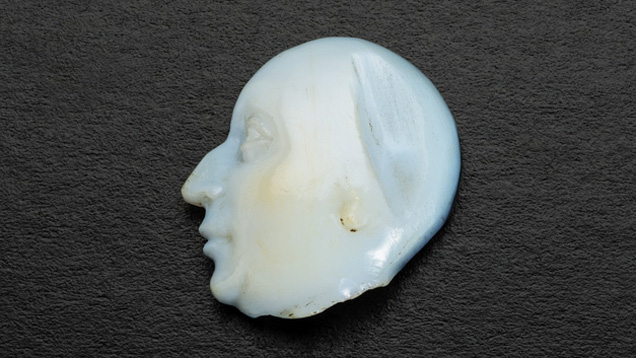

Despite the enormous historical expanse of the collection, several clues have allowed experts to pinpoint the stashing of the hoard within a few years’ range. According to Forsyth, comparing the pieces with contemporaneous portraits helps date the collection. For example, the style of dress in a cameo of Elizabeth I (figure 9, right) suggests it was most likely carved after 1575, toward the end of her reign (Forsyth, 2003; H. Forsyth, pers. comm., 2013). In fact, the cameo closely resembles the Armada Jewel (figure 9, left), a gold locket featuring an image of Elizabeth I fashioned by Nicholas Hilliard. The jewel was bestowed on Sir Thomas Heneage in 1588 to commemorate Britain’s resounding defeat of the Spanish Armada that year.

Forsyth and her museum colleagues believe that an intaglio from the collection, only recently identified, establishes a possible time frame for the hoard’s burial. In 1640, William Howard received the title of Viscount Stafford upon his marriage to Mary Stafford. A chipped, unassuming carnelian intaglio from the Cheapside Hoard (figure 10) exhibits his newly appointed heraldic badge, narrowing the concealment date between 1640 and the time of the Great Fire of London in 1666. Once again, the diversity of the collection and the presence of this flawed, inconspicuous jewel suggest that this was the working stock of a professional gem merchant or jeweler who received gems in trade, took in items for repair, or traveled extensively.

CURIOSITIES IN THE CHEAPSIDE HOARD

Furthering the theory that a working jeweler owned the hoard is the presence of an imitation gem that raises some thought-provoking possibilities. In 1610, the Goldsmiths’ Company investigated one of its own members, a goldsmith-jeweler who was making fake “balas rubies” (an old misnomer for spinel). Pendant spinel drops were extremely popular and extraordinarily expensive (H. Forsyth, pers. comm., 2013). The counterfeiter used an old recipe for quench-crackling inexpensive rock crystal quartz and infusing the surface-reaching fissures with a red dye—possibly cochineal, an insect-based dye—to produce a very realistic imitation of spinel (Nassau, 1994). Three and a half centuries later, the dye has faded to a pale pinkish orange (figure 11).

Forsyth noted that many such fakes were sold. Some even made it back to India and Africa, eventually bringing enormous discredit to the British East India Company, which was sourcing gems and jewels for the crown. That the quench-crackled quartz pendant ended up in the Cheapside Hoard casts another oblique, uncertain light on who might have owned the collection.

One of the jewels was carved long before the 1600s. It is a banded agate cameo of a Ptolemaic queen, likely Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of ancient Egypt (figure 12). She is depicted in the guise of the goddess Isis, wearing a vulture headdress. It is unquestionably Egyptian in origin (H. Forsyth, pers. comm., 2013). Both the Roman conquest of Britain, and Cleopatra’s relationship with Julius Caesar, raise tantalizing possibilities as to how it surfaced in 17th century Britain, as well as its possible origin. Egyptian and Greek carved gems were highly collectible in Renaissance Europe, and were sometimes reused in jewelry during this time.

TRADING PARTNERSHIPS AND GLOBALIZATION

The profusion of loose and mounted gems in the collection includes, among others: diamonds from India or Borneo; emeralds from Colombia; natural pearls from the Persian (Arabian) Gulf, Scotland, or possibly the Caribbean or Comoros; sapphires, rubies, spinel, and other gems from Sri Lanka and Burma; garnets from European sources or India; peridot from Egypt (figure 13); turquoise from Persia; and opal from an unknown source (figure 14). This global snapshot indicates that London’s gem merchants and jewelers enjoyed a wide array of commercial choices. It also underscores the rising significance of the Cheapside district as a trading center. England’s global outlook at the time clearly stemmed from the colonial impulses of Queen Elizabeth I. She sent explorers—Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh, among others—on expeditions around the world, with an eye toward establishing colonies and new sources of raw materials. For England, it was a global competition for power with other European countries, particularly Spain (Sinkankas, 1981). We photographed some very interesting and important examples of these gems during our visit to the Museum of London.

Corundum. Corundum was first recognized in Europe by the Greek Theophrastus and later by Pliny the Elder, as evidenced in their writings. Two important blue sapphires from the Cheapside Hoard were made available to photograph. Both are well cut, with a square outline, and paired with spinel in a pendant (see figure 7, right). The sapphires are likely Sri Lankan or Burmese in origin and contain visible rutile silk inclusions.

Following the initial classification efforts of Belgian mineralogist Anselmus Boetius de Boodt (1609), Europeans began to understand gem materials much more clearly, including the relationship between sapphires and rubies, and how to differentiate them from gems of similar color. Red gems, for example, had once been known collectively as “carbuncles” (Hughes, 1997). Thomas Nichols, an English naturalist at the time the Cheapside Hoard was hidden, furthered the leap forward in gemological knowledge. In 1652, he clearly described gem treatments as well as the sources for ruby and sapphire and other gem materials: “The best of these [rubies] are found in the island of Zeilan [Ceylon, modern-day Sri Lanka]. . . . there are excellent ones found in the [Burmese] river Pegu, the inhabitants there try them with their mouth and tongues: the colder and harder they are, the better they are,” he wrote, adding that the same deposits often carried sapphires. Nichols (1652) also reported other producers of sapphires, including India, and even some European sources such as Silesia (a region on the Oder River, mostly in modern-day Poland). Most of the rubies we viewed from this collection were smaller stones, many of them adorning an enameled perfume bottle (see figure 1). One large, mostly opaque ruby from the hoard was in cabochon form.

Diamonds. After expeditions led by Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) opened trade with the East, diamonds began to appear in Europe. The Indian mines at Golconda were the only known source at that time, and many centuries would pass before diamonds attained the status of ruby and sapphire. Around 1500, the discovery of a sea route around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope increased the supply of high-quality rough from India to satisfy Europe’s growing demand for diamonds (Lenzen, 1970).

Polished diamonds initially appeared in Europe in the 1380s. The earliest cut, the point cut, remained popular into the 15th century. It closely followed the rough diamond’s octahedral shape. The late 1400s saw the recutting of point cuts into a new style, the table cut. This was produced by removing the top point to create a square polished facet. Often the lower point was also removed to create a smaller square facet. Thus the table cut resembled a square within a square, which appealed to European interest in classical proportions during the Renaissance. Because table-cut diamonds were more brilliant than point-cut gems, they remained popular throughout the 1500s and 1600s (Tillander, 1995).

The gold ring with white enamel in figure 15 dates from the late 16th or early 17th century. It is set with a table-cut diamond that measures 8.4 mm × 8.0 mm and weighs an estimated 3 to 4 ct. With its table-cut crown and modified “scissor-cut” pavilion, it is an extraordinary survivor, as most were recut by about 1700. India is the likely source of this diamond (Jobbins, 1991; Gosling, 1995).

Emeralds. The hoard’s largest and arguably most striking item is a pocket watch set in a massive polished hexagonal emerald crystal from Colombia (figure 16). It measures an estimated 42 mm deep × 20 mm wide (Jobbins, 1991). Aside from its inherent beauty and craftsmanship, the piece serves as a fitting metaphor that says much about the time and place of the Cheapside Hoard. Emeralds from Colombia began to enter the European trade in the mid-1500s. Although Hernando Cortez had received emeralds as a gift from Montezuma in the early 1500s, an actual South American source for the gem remained elusive. But in 1537 Spanish conquistador Jimenez de Quezada seized areas of Colombia that included the emerald-rich Somondoco Valley (Sinkankas, 1981). Emeralds and gold from Nueva Granada, as Colombia was then called, were soon being exported to Spain. The Spaniards regarded emeralds as a commodity and readily traded them. By the late 1500s, these gems from the New World were making their way across Europe. The beauty, size, and intense color of the Colombian material overshadowed the meager supply from the so-called Cleopatra Mines in southern Egypt.

Invented in the late 1400s, pocket watches had improved significantly by the mid-1500s. The combination of new technology and this spectacular emerald must have proven irresistible for the watchmaker. The champlevé style of enameling, where recessed areas are carved into the metal and filled with enamel, at the center of the dial adds to the splendor of the timepiece. Forsyth believes this watch dates to the 1600s, and that the skill and craftsmanship required to manufacture this elaborate jewel suggest it was made for nobility.

A salamander hat pin, also containing Colombian cabochon emeralds, is one of the hoard’s most iconic and recognizable jewels (figure 17). It compares in style to another item in the collection, an apparent fan holder in gold and white enamel with Colombian emeralds (Scarisbrick, 1995; figure 18). Together the pieces underscore the European demand for Colombian emeralds in the late 1500s and early 1600s.

Pearls. The primary source for pearls in the 1600s was the Persian (Arabian) Gulf, where they had been traded for thousands of years (Dirlam and Weldon, 2013). These popular organic gems were also being sourced from the Gulf of Manaar, between Sri Lanka and India (Tavernier, 1676). In his description of the hoard, gem expert Alan Jobbins (1991) attributed the decomposition of the organic conchiolin to exposure to the elements. He also described the beauty revealed in the breakdown of some of the concentric layers of nacre, which is clearly evident in a pendant featuring a large pearl paired with a pale blue sapphire (H. Forsyth, pers. comm., 2013). The carving dates to the Byzantine period and depicts the incredulity of Saint Thomas, with exquisite green and white enamel detail on the reverse (figure 19). As noted, many jewels that would have contained pearls were empty due to their presumed decomposition.

Spinel (“Balas Ruby”). One of the most misunderstood yet coveted gems during the Renaissance was spinel. For its subtle differences with ruby, red spinel was known as “balas ruby.” The name was derived from a source in the Pamir Mountains of modern-day Tajikistan, where they were known as Laal-Bedashan. Marco Polo, who traveled through the area in the 13th century, used the term in his notes (Hughes, 1997).

Spinels were long thought of as rubies, perhaps because they were often intermingled with actual corundum in the alluvial gem gravels. Interestingly, spinels were much in demand—as evidenced by the counterfeit “balas ruby” contained in the hoard and the high prices fetched by these goods. One historical example of a mistaken spinel is the Black Prince’s Ruby, the most important colored gemstone in the British Imperial State Crown. This spinel was believed to be a ruby for many centuries.

Toadstone. Though virtually unknown today, this unusual gem enjoyed considerable prestige at the time the hoard was assembled. Toadstone was considered an antidote for poisons and also thought to warn of their presence by becoming hot (Kunz, 1915). Shakespeare (1564–1616), writing during this time, mentioned toadstone in As You Like It:

Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.

Three centuries later, American mineralogist George Frederick Kunz (1915) wrote:

While it is quite possible that some of the so-called toadstones may really have been concretions found in the head of the toad, by far the greater part were probably small pebbles sold as “toad-stones” to those who believed in the magic virtues of such a stone and were willing to pay a good price for one.

Many toadstones are actually fossilized teeth, approximately 150 million years old, from a species of fish called Lipodotus maximus (Forsyth, 2003). Fourteen toadstones were among the loose gems found in the hoard (figure 20). They would have been set in rings and worn as amulets for protection or to bring good fortune and prosperity (Kunz, 1913; Kunz, 1915).

CONCLUSION

Because of its centuries of concealment and the context in which it was found, the Cheapside Hoard is a supremely important collection of jewels. This unique assemblage encompassing a wide variety of gems from around the world shows fine examples of 16th and 17th century jewelry, including rings, chains, necklaces, pendants, buttons, brooches, hat or cloak pins, and watches. Functional items are also represented: tankards, vessels, utensils, a scent bottle, and even a few mystery objects. From this treasure we can glean valuable insight into the global trade and use of gems in the 1600s (figure 21).

“London has always been a trading port,” said Sharon Ament. “Even from the early Roman days it has been a place of many different cultures. The Cheapside Hoard and the history of London really come together in this museum.”

Undisturbed in a cellar in the Cheapside district of London, the gems and jewelry worn nearly 400 years ago emerged relatively unscathed. Now they are once again in the spotlight, and the world will have the opportunity to see this remarkable collection at the Museum of London from October 11, 2013, through April 27, 2014.