Insights From Inclusions

September 29, 2014

Natural gemstones are typically far more valuable than synthetics, so being able to identify them correctly is a powerful skill. One of the best ways to determine if a gemstone is natural or synthetic is to note the type and variety of its inclusions.

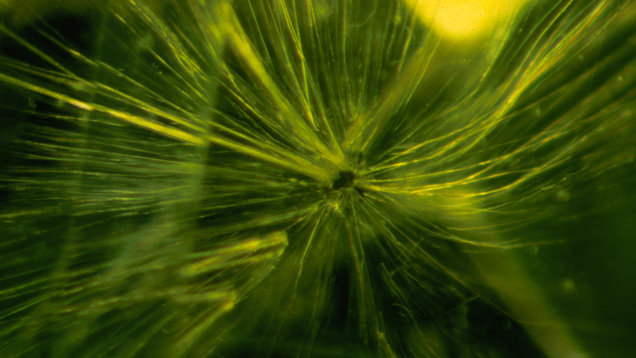

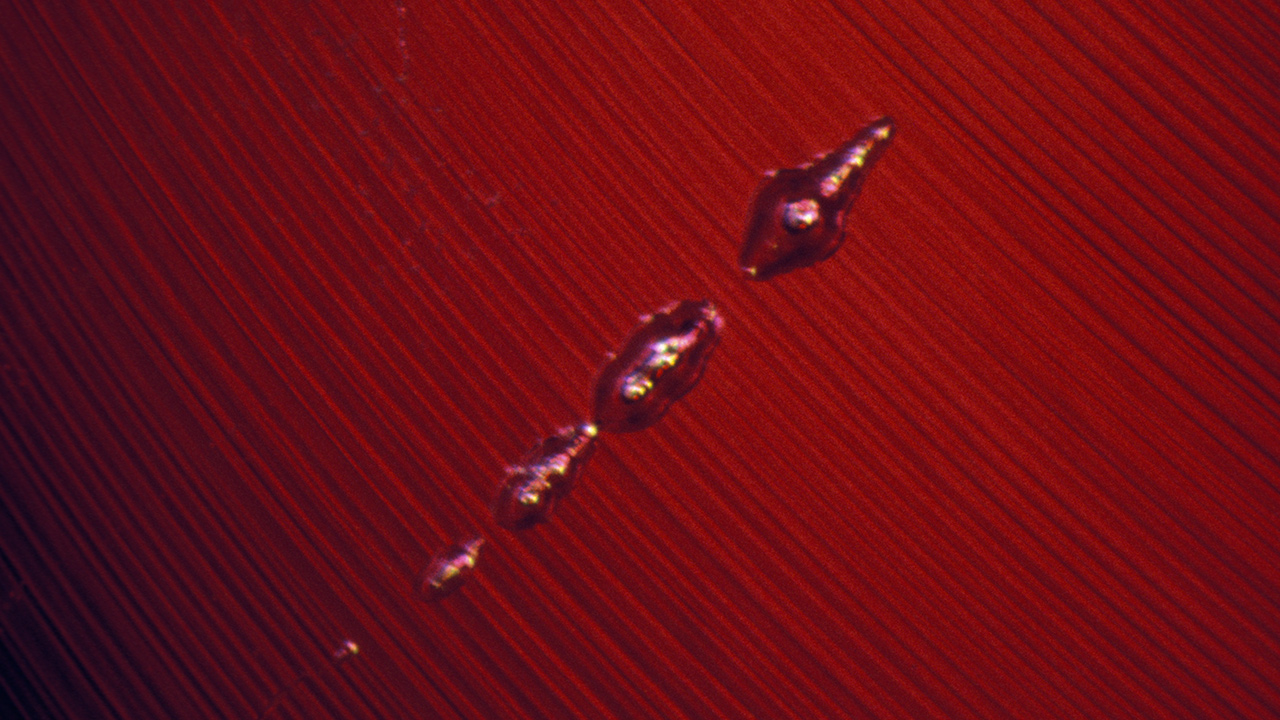

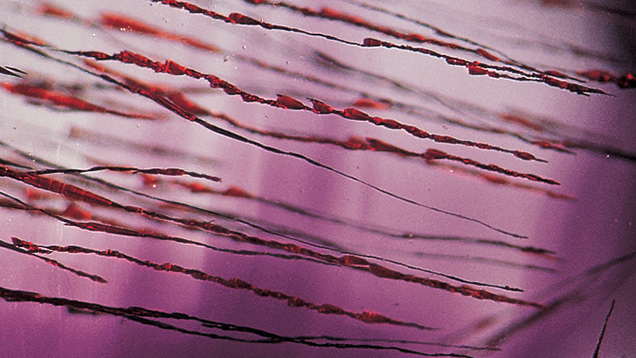

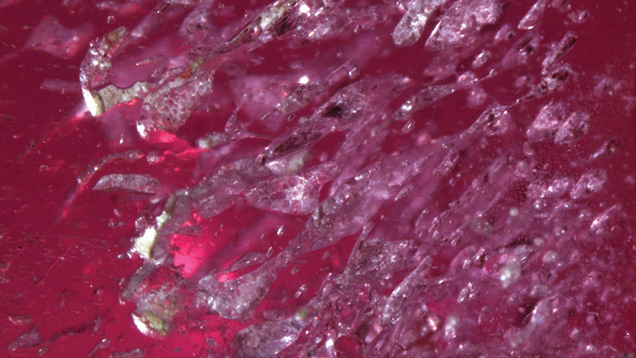

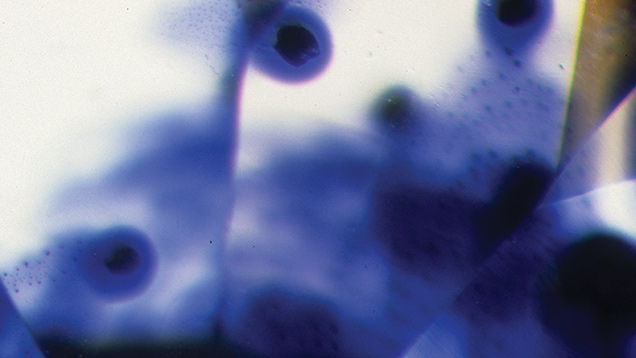

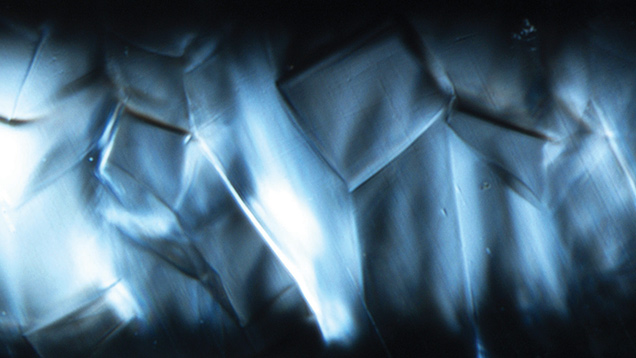

Certain types of inclusions are found more often in natural gemstones than in their synthetic counterparts. Needles, clouds, fluids, and crystals are examples of inclusions typically found in natural gemstones.

Synthetic gems generally have inclusions specific to their method of growth. These characteristics include translucent to opaque coloring, coarseness, and a web-like appearance, which are stark contrasts to natural, transparent, partially healed fracture “fingerprint” inclusions. For example, translucent to opaque-white to yellowish granular-looking flux are types of inclusions you would typically find in a flux-grown synthetic stone.

“By understanding the types of inclusions and their characteristics, you can determine if a gem is natural or synthetic. That helps you understand the stone’s history and value,” says Brenda Harwick, GIA’s manager of on-campus and laboratory gemology instruction in Carlsbad.

The three-volume Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, authored by Eduard Josef Gübelin and John Koivula, is widely considered a definitive read on the subject. To learn more about these valuable resources visit store.gia.edu and enter keyword “Koivula.”

Some GIA students become so curious about the particular types of minerals that make up inclusions that they pay less attention to the general type of inclusion they are examining.

Here’s a helpful study tip: First become adept at identifying the overall types of inclusions, and then pursue your natural curiosity as to their specific make-up. Advanced chemical and structural testing is often required to determine what they are, but rutile and zircon are some common culprits (depending on the species of gemstones).

Remember, though, it’s the type and number of inclusions that really matter – and not their precise chemical composition. Keep this in mind, and you will become a better gemologist.

Tips for Viewing Inclusions

By looking at gemstones under a microscope, you’ll see the number and general type of inclusions. Doing this can help you determine if a gem is natural or synthetic; and that information can affect a gemstone’s value.

Studying gems under a microscope also helps you create your own “visual library” of inclusions, which over time, will become references as you examine new stones.

Here are a few tips for using a microscope for this purpose.

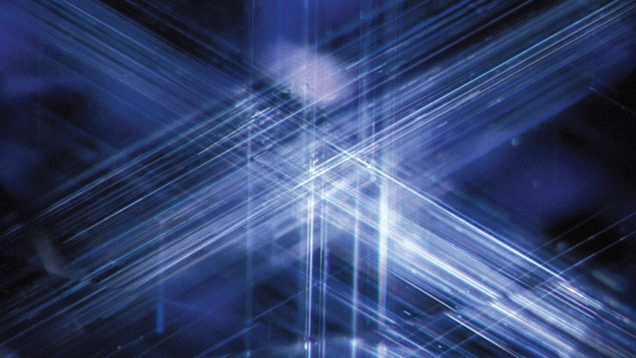

- Use a variety of lighting environments to examine inclusions, including: brightfield, darkfield, polarized light, and fiber optic illumination. This lets you see how the gemstone reacts to a controlled pathway of light, revealing valuable information about the inclusions. Each type of light may yield new information and help you see something you would otherwise miss if you only used one lighting environment.

- First look through the broadest window into the gem, which is generally the table facet, and then into the gemstone’s pavilion (this often gives you an excellent view of the inclusions).

- Be certain to rock and tilt the gemstone so that you view it from a variety of angles.