An Introduction to Simulants or Imitation Gem Materials

The jewelry industry uses the term “simulant” to refer to materials, such as CZ, that look like another gem and are used as its substitute but have very different chemical composition, crystal structure and optical and physical properties. These simulants, also known as imitations or substitutes, can be natural or manmade.

Man-made simulants

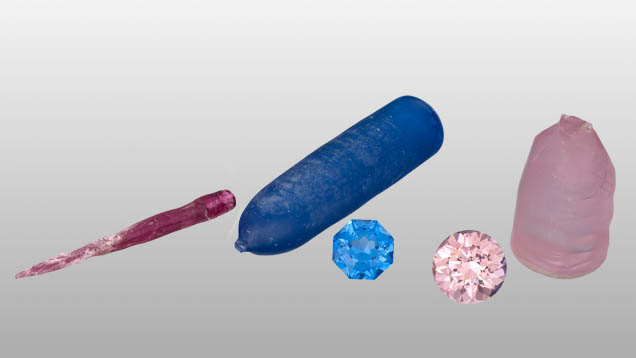

Synthetic cubic zirconia (CZ) – Numerous gems have been used as diamond imitations throughout history, but synthetic CZ has surpassed them all in popularity.

Introduced in the late 1970s, CZ is made through placing powdered zirconium oxide is inside a metal chamber and heating it to its melting point. The melt is then slowly moved away from its heat source, so that crystals grow at the bottom of the melt until the whole melt has solidified.

CZ has a Moh’s hardness of 8.5. That means it is a hard and durable gem although not as hard as diamond. Most CZ can be described as colorless, and most have high clarity with minute, if any, imperfections. CZ will, however, yellow in color over time. CZ has slightly more fire but less brilliance than diamond.

Cubic zirconia can be produced in almost any color. Pink and yellow CZs can be used as convincing pink or yellow diamond imitations. Other color CZs make good imitations of darker red, purple, blue, green or black gemstones.

Prevalence: common

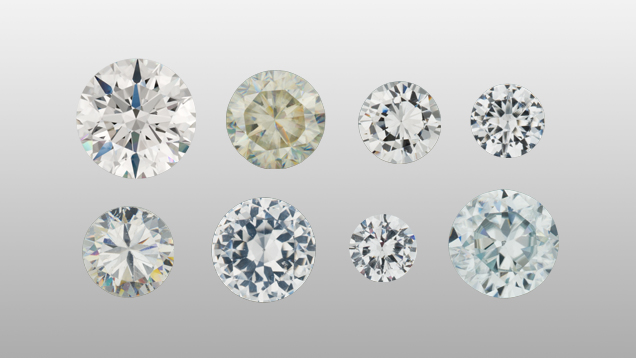

Synthetic moissanite – Colorless synthetic moissanite became popular as a diamond imitation in the late 1990s and has become a very popular engagement ring stone due to its brilliance, intense fire and durability.

Moissanite can be colorless to near colorless. Its value often depends on its degree of colorlessness. Moissanite tends to have a few more inclusions than CZ, with clarity that could be described as having minor, if any, imperfections. It has a hardness of 9.25 on the Moh’s scale, which makes it very hard and durable, although not as hard as diamond.

Moissanite has more than twice the fire of diamond and slightly more brilliance. In large sizes, one carat or above, its intense fire may give it away as a non-diamond gem. In very large sizes, its display of extreme fire is sometimes called the “disco ball” effect.

It is also different from diamond visually in that it is doubly refractive, so viewers will see a double image of its back facets. This means the inside of the moissanite may appear blurry. Some moissanites look slightly yellow or gray when viewed at certain angles.

Moissanite can come in colors such as yellow, black and blue and can be used as colored diamond substitutes.

Prevalence: increasingly common

Synthetic spinel – synthetic spinel is often used as a simulant because it can mimic the look of many different natural gems (such as sapphire, zircon, aquamarine and peridot), depending on its color. Its accurate reproduction of a wide variety of colors makes it a common choice for imitation birthstone jewelry.

Prevalence: common

Synthetic rutile – synthetic rutile was introduced in the late 1940s and used as an early diamond simulant. Made by the flame-fusion method, it is nearly colorless with a slight yellowish tint, but it can be made in a variety of colors by doping (adding chemicals during the growth process).

Prevalence: rare

Strontium titanate – this colorless manmade material became a popular diamond simulant in the 1950s. However, its dispersion (the optical property that creates fire in a faceted gemstone) is over four times greater than diamond. Strontium titanate is most often produced by the flame-fusion method and can be made in colors, such as dark red and brown, by adding certain chemicals during the growth process.

Prevalence: rare

YAG and GGG – several manmade materials have been used as diamond simulants over the years. In the 1960s, yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) and its “cousin” gadolinium gallium garnet (GGG) joined classic simulants like glass, natural zircon, and colorless synthetic spinel. YAG and GGG are also available in a variety of colors.

Prevalence: rare

Glass – manufactured glass is an age-old gem imitation that is still used today. Since glass can be manufactured in virtually any color, this makes it a popular substitute for many gems. Although it is less brilliant, glass is used to imitate stones like amethyst, aquamarine, and peridot. It can also be made to look like natural phenomenal gems, like tiger’s eye and opal, and fused layers of glass can imitate the look of agate, malachite, or tortoise shell.

Prevalence: common

Plastic – plastic is often used to imitate gemstones in inexpensive fashion jewelry. However, this modern manmade substance has also been manipulated into convincing imitations of organic gems like amber, pearl, and coral, or aggregate materials like jade, turquoise and lapis. Plastic is not a durable imitation, so special care must be taken to prevent damage.

Prevalence: common

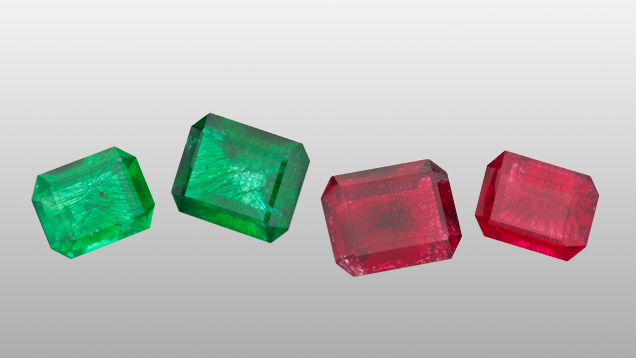

Quench crackled quartz – Natural colorless quartz can sometimes be subjected to thermal shock, known as “quench crackling.” The colorless material is first heated, and then subjected to quenching in a cold, liquid solution—such as water. The sudden contraction causes the material to develop a series of cracks that radiate throughout. Because these are surface-reaching fractures, the quartz can then be subjected to additional immersion in a dye solution, allowing the fractures to be filled with colored liquid. This makes a convincing simulant to such natural gems as emerald, ruby and sapphire, although the fractured and dyed appearance can quickly be seen under the microscope.

Prevalence: occasional

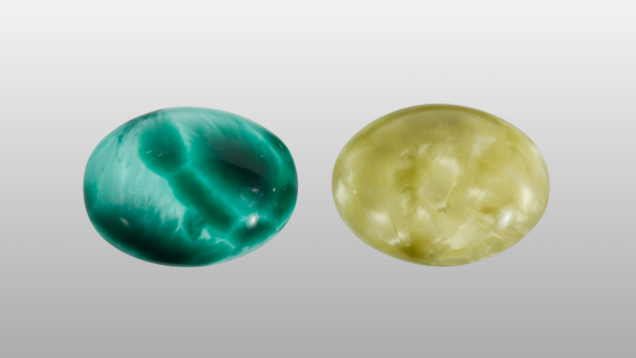

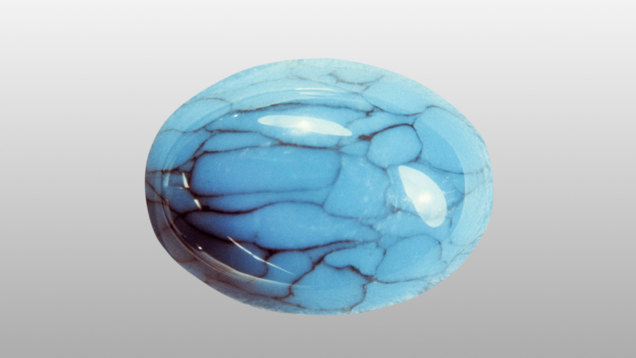

Ceramic beads – you’ve probably heard the term “ceramic” applied to clay pottery. In general, a ceramic can be any product made from a nonmetallic material by firing at high temperature. Two popular non-faceted gems, imitation turquoise and imitation lapis lazuli, are produced by ceramic processes. During this process, a finely ground powder is heated and sometimes placed under pressure to recrystallize and harden to produce a fine-grained solid material.

Prevalence: occasional

Imitation turquoise – the cool blues and greens of turquoise have attracted people for centuries. More than 5,000 years ago, Egyptian pharaohs first adorned themselves with turquoise. The familiar gem is a microcrystalline aggregate that often features attractive, vein-like inclusions of host rock known as matrix. In the early 1970s, Gilson introduced an imitation turquoise as well as an imitation lapis.

Prevalence: occasional

Imitation lapis lazuli – dark blue lapis, treasured by ancient civilizations, has been mined in Afghanistan for more than 6,000 years. The gem is an aggregate of several different minerals. It sometimes contains gold-colored flecks of pyrite that can enhance its appeal. Gilson’s lapis is more accurately considered an imitation because it has some ingredients and physical properties that are different from natural lapis.

Prevalence: rare

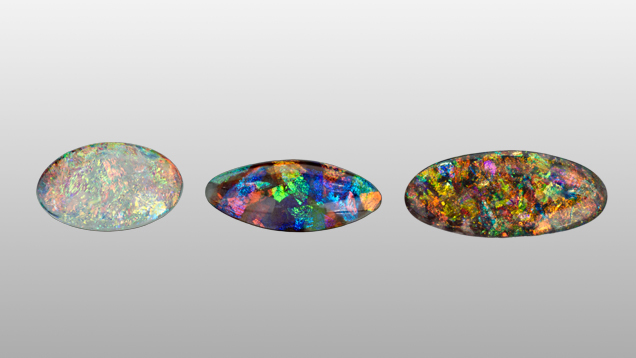

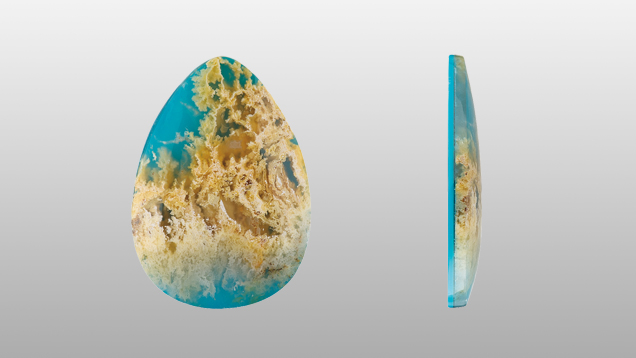

Assembled Stones

When manufacturers glue or fuse two or more separate pieces of material together in the form of a faceted gemstone, the result is called an assembled or composite stone. The separate pieces can be natural or manmade. The flat surfaces that are glued together are parallel to the large table facet of the gem so as to impart a more uniform face-up color.

Doublet – a doublet consists of two joined segments.

Prevalence: common

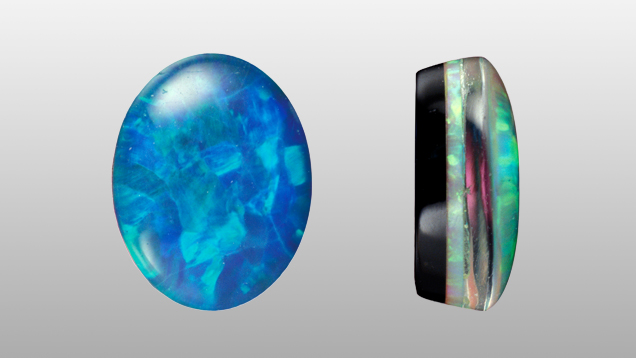

Triplet – a triplet has three segments, or two segments separated by a layer of colored cement.

Prevalence: common

Although doublets and triplets are used to imitate natural gems, assembled stones are not always imitations. This is the case with natural opal, which sometimes occurs in layers so thin that they need reinforcement to be sturdy enough for jewelry use. Black onyx, plastic, or natural matrix have served as the bottom layers of opal doublet or triplet cabochons. Opal triplets are topped with a transparent dome made of rock crystal, plastic, glass, or synthetic corundum.