Seeking the Legacy of Australian Sapphire

, , andDecember 14, 2015

The moment I held that stone up to the sun and saw a deep vibrant royal blue color throughout the sapphire…I knew I was hooked.

INTRODUCTION

Sapphire was discovered in Australia during the 1850s gold rushes and 1870s tin mining. One of the earliest written records is from 1851, when sapphire was found in New South Wales. Though the long history of sapphire mining and commercial production spans at least the past half century, Australian sapphire has not received the recognition it warrants from either the global gem and jewelry industry or the consumer market. The top-quality Australian stones were sold as being from other sources, such as “Pailin” from Cambodia. Australia’s sizable commercial-quality sapphire production and its contribution to the rest of the world, especially the current corundum trading center of Thailand, are under-recognized. The trade between the Aussies and the Thais led to the global sapphire industry’s current dynamics.

To enrich GIA’s global corundum research and learn the full story of the Australian sapphire industry, the Institute sent a group of field gemologists to explore the most important sapphire gem fields in eastern Australia. The group was led by GIA senior field gemology manager Vincent Pardieu and composed of field gemologist Andrew Lucas, Gems & Gemology technical editor Tao Hsu, assistant field gemologist Victoria Raynaud, and field cameramen Didier Gruel and Didier Barriere Doleac. The Institute’s field gemologists have covered all important sapphire fields in Australia—earlier this year another team led by Vincent Pardieu visited Tasmania’s sapphire fields (http://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/searching-sapphire-tasmanian-wilderness).

AUSTRALIAN SAPPHIRE GEM FIELDS

Of the areas on Australia’s east coast that have reported sapphire deposits throughout history, three regions are widely known as the main sapphire mining districts. From south to north, they are the Inverell–Glen Innes region on the New England Plateau in New South Wales, the Rubyvale-Anakie district in Queensland, and Lava Plains in northern Queensland. All Australian sapphire deposits are alkali basalt–related. Stones are recovered from both secondary deposits along current or previous watercourses and primary or reworked pyroclastic flows or volcanic mudflows (lahars). Taking off from Sydney, the GIA team visited Inverell, Rubyvale, and Lava Plains. Sapphire samples were collected at all three locations.

to Cenozoic basalts. From south to north, they are the Inverell field, the Anakie field, and

the Lava Plains field.

The Inverell–Glen Innes region is one of the world’s main suppliers of sapphires. The sapphire deposits are found in both the volcaniclastic rocks and their reworked alluvial placers but not in the lava flows. Due to weathering and vegetation cover, basaltic lava flows can barely be seen as ridges or terraces of different levels. The original volcanic edifice is not visible. Sapphire was reported in northern New South Wales for the first time in 1854, but the first commercial mining began in 1919. The 1960s and 1970s saw the heyday of mechanized sapphire mining in this area due to high demand from Thai buyers (leading to a price increase) and the introduction of new mining techniques.

At the Kings Plains deposits, our team visited a mine under the operation of Wilson Gems & Investment, about 45 kilometers northeast of the town of Inverell. The Wilson family is among the first miners who began working on the deposits in the sixties. The Kings Plains deposits are considered some of the richest sapphire deposits ever mined. According to owner Jack Wilson, there could be more than one sapphire-bearing layer, which might reflect multiple volcanic eruptions. During our visit we saw the miners extracting the clay-like sapphire-bearing layer below the topsoil. The washed material would eventually be handpicked to separate the rough sapphire crystals for further sorting. The majority of the production is cut in Thailand and exported to Russia.

During our visit to Inverell, we had the opportunity to see the Billabong Blue sapphire mine. In contrast to the Kings Plains open-pit operation, this mine is an alluvial deposit along old stream channels. The sapphire-bearing gravel layer is quite shallow on the currently exposed profile. Although there was no active mining when we were there, our team was able to find some stones in leftover washed gravel from the jig from the last production day.

After crossing the state border into Queensland, we visited a second sapphire field: the Rubyvale-Anakie area in central Queensland. Government surveyor Archibald John Richardson discovered the first sapphire in the region while surveying the railway in 1875. Soon he quit his job and moved to Anakie, filed a claim, and started digging for sapphire. Based on the numerous well-preserved basaltic plugs in this area, many people believe that the basaltic volcanism brought the sapphire to the surface, just as in the other sapphire fields.

region are very proud of their sapphire culture. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Sapphire is recovered mainly from current and previous river channels in this region, and no one is reported to be working a primary deposit yet. The sapphire-bearing sediments are above the granitic basement rocks, show large variation in thickness, and reflect a very high-energy local sedimentary environment.

The sapphire mining boom that began in the early 1970s with the introduction of mechanized operations faded later that decade. Since then tourism and fossicking (hobbyist mining) have grown considerably. Today a good number of mechanized miners and hand tool miners still work on the field, generating a commercially viable amount of stones every year.

The team was hosted by local sapphire miner Peter Brown, who is also an experienced sapphire cutter. Peter’s small-scale operation is very efficient and can even be handled by one person. The team also visited a large-scale machinery operation in Rubyvale, the Capricorn open-pit operation run by Richland, and a small-scale underground mine in Willows Gemfields west of Anakie.

hand-mining tools. Their screening and washing methods require little water and could be

adopted in artisanal mining areas around the world. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

After a short break in Brisbane, the group flew to Cairns, a city in the far north of Queensland. There we met our local contact, Michael McCann, president of the Mt Rosey Mining Company, who would guide us to visit the Lava Plains sapphire field. The Mt Rosey mine is about 250 kilometers southwest of Cairns, right outside the southern border of Undara Volcanic National Park. Compared to the other two field areas, the volcanic landforms in the Lava Plains field are much easier to see because they represent the most recent volcanic activities on this continent. The sapphire-associated McBride Basalt has an age range of 8–0.1 Ma. Cinder cones, craters, partially collapsed crater walls, and lava flows can all be easily mapped. Sapphires are found in placers and sediment accumulations along linear depressions either within the lava flow surfaces or associated with fissures or faults.

The Mt Rosey mine camp is at a historical mining operation called the Thai Sapphire Mine. Old mining facilities and multiple human-built water dams are still at the site. Since there is no available written record of this mine, the reason the Thai miners left is unknown. We also visited another historical mining site named The Scot’s Mine. Based on the discarded mining and processing machines, the mine was likely quite large. There is no available record of this mine either.

THE STONES

Australian sapphires are associated with volcanic activity and are often referred to as basalt hosted. The sapphire deposits in Thailand, Cambodia, China, Vietnam, and Nigeria are also basalt hosted. The iron content of these types of deposits is usually higher than that of sapphires that form in marble, like in Myanmar, so the blue color is often darker. There is also often a stronger green pleochroic color element.

also produce bright blue material. Photo by © GIA and Tino Hammid.

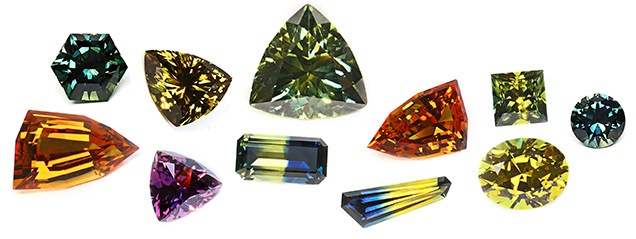

This dark blue material makes up the vast majority of Australian sapphires, with some almost black. However, some brighter blues can also be found, as well as yellows, greens, and parti-colored stones that show a combination of colors, like green and yellow or blue and yellow. The parti-colored stones are highly prized by the miners and often given to their wives, while foreign wholesale buyers are not as interested. Pink sapphires are rare and orange sapphires extremely rare. Australia is also known to produce black star sapphires and rare green star, yellow star, and blue star sapphires.

THE PEOPLE

Our team was privileged to interact with members of the Australian sapphire industry who had decades of experience and had seen the market go through many changes. Our expedition guide, Terry Coldham, with 50 years of experience in mining, cutting, marketing, and wholesale, is one of the leading authorities in the industry and has also been extensively involved in the global sapphire industry.

Some of the miners we met had seen the dramatic changes as the industry moved from small-scale to larger operations during the boom years of 1967 to 1979, and now to fewer mining operations with often more vertically integrated small-scale business models. To be competitive all the operations had to be extremely efficient and innovative.

Peter Brown arrived in the Rubyvale, Queensland, sapphire gem fields in 1974, driving an old VW Beetle, and set up camp. He grew his own vegetables and shot wild game for meat. Contemporaries remember him as a penniless hippie.

Since then Peter and his wife, Eileen, and sons have owned and operated successful sapphire mining operations. The family cuts a percentage of its own stones, manufactures jewelry, and owns a retail store called Rubyvale Gem Gallery. They also converted a miner’s cottage into an inn for tourists and started a restaurant adjacent to their store. The Brown family operates a complete mine-to-market enterprise.

the Queensland Tourism Industry Council. Photo by Andrew Lucas/GIA.

Jack Wilson has also seen the changes over the years and currently operates an open-pit mining operation with his son. His father started mining sapphire in the New South Wales fields in 1964. Jack now mines and runs the business with his wife and two sons and a small crew at Kings Plains. He adapted a magnetic separator to separate the magnetic ore from the sapphire for greater efficiency in processing. Australian sapphire miners have learned to be very efficient, to do more with less so they can be competitive globally.

Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

Jack Wilson has found that to be competitive globally, he must cut the stones in a factory in Thailand and sell the finished stones as opposed to selling only rough on the wholesale market. He and his family also operate a retail store in Inverell, where they sell finished sapphires and jewelry to tourists.

We interacted with sapphire miners including Daryl Mosly, who runs a very efficient mechanized open-pit mine; small-scale miners working underground with jackhammers; a new large-scale open-pit modern operation called the Capricorn mine (due to its proximity to the Tropic of Capricorn) operated by Richland, the former mining company at TanzaniteOne; and another new operation at the Lava Plains fields, managed by Michael McCann. All in all we met a fascinating mixture of innovative and efficient independent miners, small-scale miners and hobbyists called fossickers, and new larger-scale operations.

AUSTRALIA’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE GLOBAL SAPPHIRE INDUSTRY

Over the decades Australia has made major contributions to the global sapphire and colored gemstone industries. In the late 1950s to early 1960s, Australian sapphire miners converted jigs used by tin miners near Inverell for use in sapphire mining. As time went by, simple sluices used for sapphire recovery now incorporated pulsating jigs and trommels in a more sophisticated system. Sapphire miners also discovered that spinel and some of the iron oxide materials could be separated using a magnetic separator, greatly reducing the amount of material that had to be handpicked. Variations of these jigs are used in many colored gemstone mining areas, including Southeast Asia and Africa.

The connection between Australia and Thailand has helped shaped the modern sapphire market. The demand from Thailand led to the boom years of production from 1967 to 1979. This fueled more mining operations and larger mechanized operations. In turn the influx of large quantities of Australian sapphire greatly helped to expand the Thai sapphire cutting, treatment, and trading market, helping to push Thailand to the forefront of the global sapphire industry. A leading factor was Thai dealers implementing heat treatment to clarify the Australian stones—previously unusable sapphires from Australia could then be faceted and sold in jewelry around the world in large quantities. The rough from Australia was used to cut large quantities of calibrated blue sapphire to supply mass jewelry manufacturers and then large retailers.

This not only provided the fuel and capital to expand the Thai industry but also influenced consumers around the world to see dark blue sapphires from Australia as the norm. Later other volcanic-associated sapphires from Thailand, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Nigeria would come to consumers. Thailand would become the center for cutting and treating sapphires from all sources, including the geuda sapphires from Sri Lanka in the late 1970s, when they treated the translucent grayish material to create a very attractive blue color.

sapphire miners. Photo by Vincent Pardieu/GIA.

In the last few years, demand has increased, but it is still not nearly as high as in the boom years. Thai buyers are coming to the Australian sapphire fields again, looking for larger dark blue-black stones they did not want before. Beryllium treatment can give these stones an attractive golden color. A newer treatment has helped to create a demand again.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology. Andrew Lucas is manager of field gemology for education at GIA Carlsbad; Vincent Pardieu is senior manager of field gemology at GIA Bangkok.

DISCLAIMER

GIA staff often visit mines, manufacturers, retailers and others in the gem and jewelry industry for research purposes and to gain insight into the marketplace. GIA appreciates the access and information provided during these visits. These visits and any resulting articles or publications should not be taken or used as an endorsement.

The authors want to thank Terry Coldham, who was instrumental in planning this trip, drove tirelessly across the Australian outback, and generously shared his extensive knowledge from over 50 years in the sapphire industry; the Gemmological Association of Australia; and all of the miners, cutters, wholesalers, and retailers in the Australian sapphire industry.