Rough Diamond Auctions: Sweeping Changes In Pricing and Distribution

ABSTRACT

Since 2007, rough diamond prices have become extremely volatile. One reason is the growing percentage of rough diamonds now sold by tender and live auctions rather than the century-old system of marketing rough diamonds at set prices to a pre-approved clientele. This report explains the tender and live auction processes and discusses their effect on the rough diamond market, including pricing and the opening of a market that was once difficult to enter.

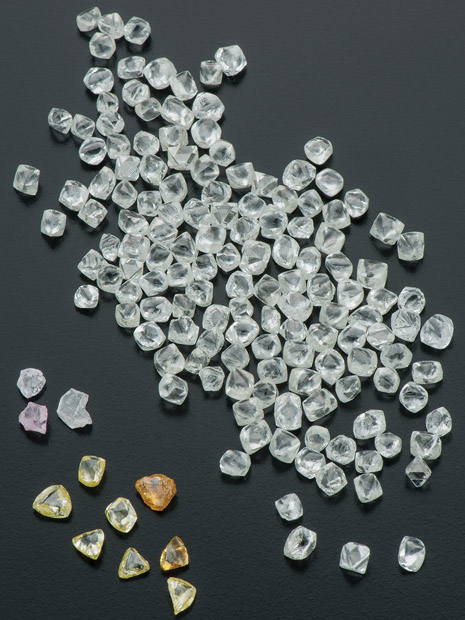

rather than the traditional set-price sights. These rough diamonds from the Kao mine in

Lesotho were auctioned in Antwerp in November 2014. They include three light pinks

(1.10 carats total), eight yellows (3.13 carats total), and a large group of colorless

diamonds (68.79 carats total). Photo by Robert Weldon/GIA.

BACKGROUND

In 1888, De Beers Consolidated Mines succeeded in taking control of the diamond mining operations around Kimberley, South Africa, following a lengthy battle that pitted its founder, Cecil Rhodes, against rival Barney Barnato. The Kimberley mines, discovered in the early 1870s, yielded millions of carats each year, most of which were sold into the market at wildly fluctuating prices (“Diamonds,” 1935). Rhodes and Barnato both believed that controlling production was essential to stabilizing prices. After Rhodes prevailed, gaining control of Barnato’s Kimberley Central Diamond Mining Company, De Beers signed a contract with 10 distributors in London that would buy all of its production. This group of diamond houses was dubbed The London Syndicate (“Diamonds,” 1935).The idea originated with Barnato’s nephew, Solly Joel, a De Beers director and diamond wholesaler whose firm was part of the original Syndicate. Joel believed that regulating sales through a small number of noncompetitive outlets was the key to maintaining stable rough diamond prices and an orderly supply chain. Another member of the original syndicate was Dunkelsbuhler & Company, managed by a young broker named Ernest Oppenheimer.

The Syndicate nearly collapsed during the financial crash of 1907 and again during World War I, when mining was suspended. Oppenheimer gained backers from the United States to take over the newly discovered coastal mines that Great Britain wrested from the former German colony of South-West Africa (now Namibia) after the war. That venture was named the Anglo American Corporation. Oppenheimer eventually leveraged Anglo American’s highly profitable operations to take over both the Syndicate and De Beers by 1929, in effect controlling most African diamond production directly through mine ownership or indirectly through the Syndicate, which also distributed production from other mining operations outside De Beers’s ownership.

Six years later, with the Great Depression causing a drastic drop in diamond sales, Oppenheimer dissolved the Syndicate and directed all rough sales through a new marketing subsidiary called the Diamond Trading Company (DTC). The DTC mixed rough diamonds from all sources, sorting them by quality, shape, and weight (figure 2). This allowed the DTC to set standard selling prices for each category of rough instead of charging different prices from each producer. It also established the modern sight system, in which selected clients would be permitted to buy directly from the DTC at 10 six-day sight periods during the year. All sales were “take it or leave it,” with immediate payment required and no negotiating permitted. Prices were adjusted upward when market conditions warranted, but never downward. The DTC also served as a market regulator: In periods of slack demand or overproduction, it would stockpile rough diamonds or impose production quotas on mining operations (“Diamonds,” 1935).

Charterhouse Street in London. Photo courtesy of the De Beers Diamond Trading Company.

De Beers’s approach to rough market control changed as well. Through nearly all of the last century, the company commanded 75–80% of world rough diamond sales. De Beers controlled not only production from its own mines but also the output from the former Soviet Union, starting around 1963, as well as Australia’s Argyle mine from 1983 and a small portion of Canada’s Ekati mine from 1998. In addition, the company operated buying offices in a number of African countries with large alluvial production, including Angola, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and Sierra Leone, to take in portions of diggings from artisanal miners (Even-Zohar, 2007a). Until the early 21st century, the 15–20% of rough diamonds sold outside De Beers’s sales offices were generally traded through long-established networks of dealers in source countries. These were distributed to large rough brokers in Antwerp, who in turn sold them into the diamond pipeline. Some of these transactions were completed in Antwerp’s legally sanctioned diamond clubs, and others were off-the-books “gray market” deals (King, 2009).

While the Soviet Union classified its yearly production figures as a state secret (including its sales arrangement with the DTC), it was generally estimated to account for one-fourth of DTC sales, making it the world’s third-largest diamond producer by value behind South Africa and Botswana (where production began in 1970). Thus, while De Beers’s own operations accounted for about 45% of rough production by value through the 1980s, the share it actually controlled was 80% (“The diamond cartel…,” 2004).

The DTC’s control over the rough diamond market began to wane in the early 1990s, after the breakup of the Soviet Union ended the central government’s tight grip on provincial resources. The Kremlin, in cooperation with the Sakha Republic, where most of the country’s diamonds are mined, created a mining and marketing organization called Alrosa (Shor, 1993). While Alrosa was still in its formative stages, some Russian government officials began releasing millions of carats of gem-quality diamonds into the world market under the guise of “technical” (industrial) stones that had been exempt from the sales agreement with De Beers (Shor, 1993). This depressed polished diamond prices for several years, especially with the smaller stones comprising the vast majority of these goods.

In 1996, Australia’s Argyle operation, owned by Rio Tinto, became the first major producer to leave the DTC sales arm. Argyle was then the largest source of diamonds by volume—more than 40 million carats yearly—though the material was predominantly lower in quality. Rio Tinto, whose executives had long chafed over the production and sales quotas De Beers levied on its operation, established its own sales office in Antwerp, as well as a selling system similar to De Beers’s sights (Shor, 1996).

In 1998, the large mining company BHP Billiton commissioned the first Canadian diamond mine, Ekati. BHP signed a three-year agreement to market 35% of its production through the DTC while selling the remainder through its own sales channel at fixed prices, a system akin to De Beers’s sight system (figure 3). When Diavik, another large Canadian mine majority owned by Rio Tinto, came on line three years later, BHP ended its sales agreement with De Beers, marketing all of its production through its own offices. Rio Tinto integrated the production from Diavik into its Argyle sales operation.

At the same time, De Beers itself contributed to the rough market’s fragmentation by divesting most of its aging South African mines to smaller companies. It sold its Premier mine (now called the Cullinan), the Finsch mine, its Kimberley operations, and several smaller prospects to Petra Diamonds, while its Namaqualand properties went to Trans Hex.

These changes brought a sharp decline in De Beers’s market share and, with it, the ability to dictate rough prices. In 2003, De Beers’s mines, which it owned outright or in partnership with the governments of Botswana and Namibia, produced just under 43.95 million carats and still commanded a 65% market share by value, 55% by volume. By 2012, De Beers’s production had declined to 27.9 million carats (De Beers Group, 2012); with no contract sales, the company’s share of the rough diamond market slipped to approximately 40% by value and 29% by volume.

Thus, within a decade, the production and sale of rough diamonds passed from the control of one major company with a stated priority of maintaining price stability to a multichannel environment, with major players such as Rio Tinto, BHP, and Petra eschewing market custodianship in favor of maximizing sales by adjusting prices to market conditions. This policy required the creation of a flexible pricing mechanism, setting the stage for new avenues of marketing rough diamonds.

THE RISE OF TENDER AND AUCTION SALES

Before 2000, the use of tender auctions to sell rough diamonds was limited primarily to Rio Tinto’s small production of fancy pink diamonds. Starting in 1985, the company held an annual sale of these stones at a luxury hotel in Geneva, surrounding the event with a strong publicity push. Producers of saltwater cultured pearls had been using the tender auction model for decades, conducting sales in Japan and Hong Kong and experiencing, over the long term, much greater price volatility than rough diamond producers (Shor, 2007).Smaller mining companies that entered the market during the early 21st century began adopting tender/auction sales instead of dealing through brokers as their predecessors had done. Some of these companies, such as Petra Diamonds and Gem Diamonds (figure 4), were publicly traded and required a more transparent pricing model to comply with securities regulators. Meanwhile, the emerging diamond center of Dubai began hosting rough tenders in 2005 through the newly formed Dubai Diamond Exchange. Global Diamond Tenders, based in the United Arab Emirates, conducted the first sales from production of small mining operations in southern Africa, selling 435,000 carats for US$66 million. That year, Dubai saw the trading of 1.9 million carats of rough, valued at $2.36 billion (Golan, 2005).

stake in the mine and markets all of its production, began selling all of its approximately

100,000-carat yearly production by tender auction after restarting operations in 2006.

Photo by Russell Shor/GIA.

The remaining 30% of the rough went, through direct sale, to cutting firms in the Northwest Territories and to some retailers. Beginning in 2004, BHP added a trial tender sale, a market window channel (a limited sales channel for sellers to gauge prices and demand), and a separate channel for “special” stones over seven carats. The trial tender sales, which consisted of 20 assortments, ranged from $200,000 to $500,000 each. Generally the bids from customers came in a few percentage points above BHP’s price for comparable goods over the trial period, so the company expanded its tender auction to 60% of production (mostly melee goods) in September 2008, with a full conversion to tender sales in February 2009 (Golan, 2008).

BHP’s Ekati mine produced 6% of the world’s diamond supply in fiscal year 2007—3.3 million carats—with a revenue of $583 million. BHP’s tender system was divided into three channels: a spot auction, term auctions, and special sales. The spot auction was based on single transactions. Because there were a number of similar parcels or splits offered at each sale, all bids above the minimum reserve price were averaged out to what BHP called the “clearing price” and sold at that price. While the final sale price would be the same for all winning bidders, the reward for higher bidders was that they received larger allocations if the demand exceeded available supply for a particular deal. In a term auction, the company offered an 18-month supply contract with auctions conducted in a different system, as well as special sales for large stones over seven carats. Term auctions employed what is known as an ascending clock, lasting for three hours during each sale period. Prices for each split opened at a small discount below the prices set by the spot auctions and steadily rose via online bidding until the three hours expired, or until prices reached the point where bidders declined to raise their offers.

BHP conducted the third type of auction for special stones larger than seven carats in three sales each year. Stones were offered individually or in small lots that grouped several similar rough stones. The sale used the ascending clock format, which was believed to provide the truest price discovery (Cramton et al., 2012).

The bidding process was designed to achieve “true” market prices by averaging the clearing price, which would reduce the influence of speculative bidders and ensure that all serious bidders received goods. This process would also prevent buyers from colluding to limit prices by keeping a large client base spread around the world and establishing reserve prices based on extensive market knowledge (Cramton et al., 2012).

BHP began phasing in its regular tender auction sales in July 2008, selling more than half of its production through this avenue. It completed the process by February 2009. The move’s timing, coming as it did in the midst of the gravest financial crisis since the 1930s, ensured controversy.

In the fall of 2008, after news of the near collapse of the global financial system, the rough diamond market, along with most other economic activity, saw a plunge in demand. De Beers continued to hold its regular sights but at a greatly diminished level, announcing it would reduce rough sales to 50% of pre-crisis levels. But sights in early 2009 were down much more—just $135 to $150 million compared to $750 million the previous year (Golan, 2009a). The company also suspended or severely curtailed its Botswanan and Namibian operations, for which there was little demand. De Beers found itself in the extraordinary position of having to borrow $500 million from its shareholders to maintain cash flow (Even-Zohar, 2009a).

Other major players in the industry were also affected. Russia’s Alrosa, the world’s second-largest diamond producer, continued mining at pre-crash levels but sold most of its goods at unspecified discounts to Gokhran, the Kremlin’s stockpile of precious materials. Rio Tinto cut back production in its Argyle and Diavik mining operations by 12% in the fourth quarter of 2008. The next year, it shut portions of Argyle for maintenance (Golan, 2009b) while adjusting prices downward—nearly to the levels of BHP tenders. Rio Tinto made no formal announcement on prices, so the extent of its discounting did not become known until early 2010.

BHP, however, continued to sell Ekati’s full production. Prices at its October 2008 tender fell 35–45% from the previous month and continued to slide another 10–15% through February 2009. Critics of BHP’s move to the tender system blamed the company for undermining the market and adding to the diamond industry’s difficulties (Golan, 2008). Yet the company benefited greatly; BHP’s revenues during this period actually exceeded De Beers’s because it was able to sell its entire output instead of restricting sales and curtailing production (Cramton et al., 2012). Conversely, when prices began recovering after June 2009, BHP’s prices accelerated much more rapidly than those of other producers.

The economists who created the tender sale model for BHP wrote in a 2010 evaluation that the process offered a number of advantages to mining companies over the fixed-price sales employed by De Beers and other large producers, including:

- True market price discovery. The study claimed that De Beers had underpriced its rough for many years, which helped create the supply-driven market.

- Getting the premium value from bidders who wanted only the quantities and qualities of rough they needed, as well as a consistent supply. In short, buyers would be bidding highest for their preferences. Under the De Beers sight system, clients were usually obliged to purchase goods for which they had no current use, requiring them to sell that material to other diamond firms.

- A competitive bidding environment, which usually resulted in higher prices and getting goods into the hands of clients who valued them the most.

- Pricing transparency (Cramton et al., 2012).

- The competitive nature of bidding could compromise the regular supplies necessary to maintain a stable diamond manufacturing business. Without such supply stability, diamond industry banks would be reluctant to finance manufacturers’ operations.

- The bidding process encouraged speculative buying, especially from large companies that might want to dominate sales and push prices beyond the reach of smaller manufacturers. Ultimately this would work against the mining companies by putting them at the mercy of a few large buyers.

- Prices could become very volatile, cutting into profits and further discouraging banks from financing rough purchases (Ganz, 2011).

The first auction realized prices ranging 12–18% above comparable goods sold at De Beers’s sights, because most of the buyers believed that rough prices were rising sharply enough for them to recoup their premiums over the long run (Even-Zohar, 2008). Eighty companies based in Hong Kong, Tel Aviv, Antwerp, and Mumbai bid on the 300 lots offered at online auctions (De Beers Group, 2008). By the year’s end, Diamdel had reported sales of $444 million, but the percentage sold at auction remained unspecified because the company had included set-price transactions by the Hindustan Diamond Company (the Mumbai branch of Diamdel).

The following year, Diamdel did not report a sales figure, noting the rapidly deteriorating demand for rough as the world economic crisis took hold. The company revealed that it had sold 85% of the 695 lots offered at its first presentations, with 88 companies participating. By 2011, sales had increased 30% over the previous year to $405 million, with 2,614 auction lots offered and 152 firms placing winning bids (De Beers Group, 2011). Using Diamdel’s 70% auction sales as a guide, an estimated $310 million worth of rough was sold through this channel.

In 2012, Diamdel was renamed De Beers Auction Sales and began selling 100% of its rough through online auctions. That year, however, saw the company’s production reduced by a severe accident at its largest mine, Jwaneng in Botswana. Furthermore, growing liquidity problems in the diamond industry forced De Beers Auction Sales’s total down 12% to $356 million, from 151 online auctions that offered 3,807 lots totaling an estimated 2.7 million carats. The company noted that despite the slowdown in the rough market, “competition in short-term rough diamond buying opportunities is intensifying as more players adopt the auction sales and pricing approach” (De Beers Group, 2012).

In 2013, Diamdel and its online provider, Curtis Fitch, instituted forward contract sales in addition to its spot-market bidding system to help clients develop supply continuity. The first contracts, for three-month supplies of specific sizes and qualities, began in December 2013. The company planned to extend contracts to one year in 2014.

According to De Beers, the new forward contract sales would provide customers the opportunity to secure longer-term supply at auction events and enable more effective planning and commitment to longer-term agreements with their own customers. “The forward contract sales offer customers the opportunity to bid for future supply of the types and quantities of rough diamonds they require, when they require them. The new proposition will complement current spot auction events,” announced De Beers Auction Sales senior vice president Neil Ventura. The purchase price for the volume of rough diamonds in a forward contract would be determined by a customer’s bid relative to the spot price for the same type of goods at the De Beers Auction Sales spot auction when the contract matured (Odendaal, 2013).

Within two years of BHP’s and Diamdel’s adoption of the tender system, most smaller mining companies, seeing how the returns had improved, moved from selling through contracted rough dealers to tendering their own productions. By 2010, as much as 20% of all rough production worldwide was being sold through some form of auction, and this had become a key price driver in the rough market (R. Platt, pers. comm., 2013). Rio Tinto, currently the world’s third-largest diamond producer, announced in early 2010 that it would tender a “small percentage” of its Diavik production to gauge price levels. After the initial sale, several longtime Rio Tinto clients claimed they were priced out of the tender by the newer companies invited to bid (Golan, 2010).

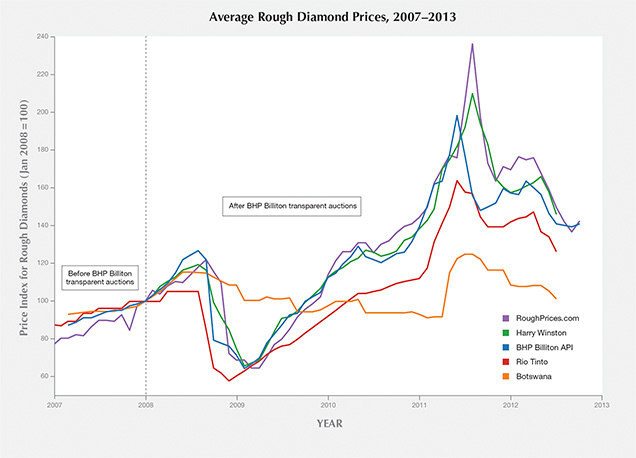

A BHP economic study confirmed the volatility of the rough market from mid-2009 through 2012. The study found that average prices, which had been slowly rising through most of the past decade (with the exception of the deep plunge late in 2008), more than tripled between June 2009 and March 2011. BHP tender prices led these increases by one month, suggesting that bidders in other tenders, as well as set-sale producers, were following its ascent. Similarly, in early 2011, after disappointing Christmas sales of diamond jewelry in the U.S. cooled the market, BHP’s sales were the first to fall, giving up about one-third of their gains by year’s end. Fixed-price producers De Beers and Rio Tinto showed much less volatility, but their prices remained well below the tender sellers’ (figure 6). But in December 2010, Diamdel chief executive Mahiar Borhanjoo denied that the company’s auction results were causing the rapid rise of rough prices at De Beers’s sights, claiming that auction results were only one of many data sources the company used in pricing its set-sale sights (Shishlo, 2010).

Fusion Alternatives holds several consolidated producers’ sales each week in its offices. Each sale consists of about 25,000 to 30,000 carats, including larger stones from Namakwa Diamonds’ Kao mine in Lesotho, with 30 to 50 buyers participating. Company executives say that prices fluctuate from one sale to the next but maintain that competitive pressure in the auction setting is only one reason.

“Of course some buyers will overpay to obtain certain goods,” says Raphael Bitterman, a partner in the company. “But there are many factors at work to affect prices and demand today: the wild changes in exchange rates, particularly the rupee; the credit standing of the buyer; and, of course, the banks’ changing credit requirements.”

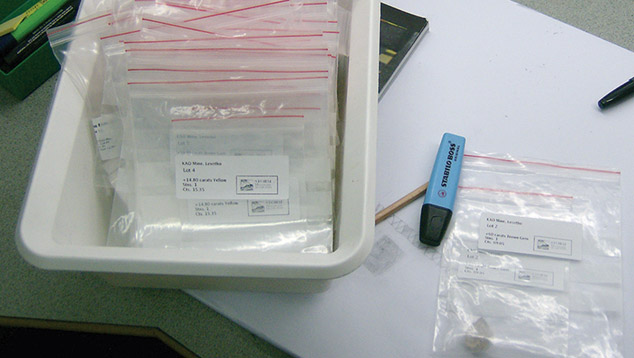

Tenders are often more focused on specific sizes and qualities than the larger sights, where clients are usually obliged to buy rough for which they have no immediate use. Larger companies can absorb these goods and sell them—often profitably—into the secondary market, but small operations cannot assume this financial burden up front. Similarly, manufacturing is becoming more specialized for niche markets, and manufacturers now have very specific needs. Tender sales give smaller players access to direct supplies of rough. For instance, Fusion Alternatives will sell rough parcels as small as $25,000 to $50,000 (about 10% of a minimum De Beers sight) to small cutting firms (figures 7 and 8). This helps small manufacturers source rough to grow their business, says Bitterman, while staying price-competitive with larger firms.

brown, was sold by Fusion Alternatives at a December 2013 tender in Antwerp. Photo

by Russell Shor/GIA.

Another significant move toward the auction system came at the end of 2013, when De Beers began auctioning a portion of its Botswana production through a newly formed government enterprise called the Okavango Diamond Company. Okavango is actually a hybrid set-price/auction setup that purchases rough allocations from Debswana—the fifty-fifty joint venture between De Beers and the Botswana government—for a fixed price and then sells the rough in auctions held every five weeks. Okavango’s plan is to market 12% (increasing to 15% within two years) of Debswana’s production, representing about $400 million yearly, or 2.5 to 3 million carats (Robinson, 2013b).

While the company vets each potential client that registers to buy, the process is not nearly as cumbersome as the lengthy application De Beers requires for its sightholders. Consequently, about half of the clients are nonsightholders. As with other tender sales, rough is divided into various size, shape, and quality categories and then subdivided into parcels. Special stones 10.8 carats and larger are auctioned separately. Every lot is available for a full day of viewing before the scheduled auction. The auction is held online during a three- to four-hour period (M. ter Haar, pers. comm., 2013; Robinson, 2013b).

The first pilot sale of 123,000 carats, held in August 2013, netted a total of nearly $20 million (Wyndham, 2013). Some categories of rough sold as much as 51% higher than comparable De Beers goods. These prices were surprising, considering that throughout 2013, De Beers clients had deferred buying as much as one-quarter of their regular sight allocations, presumably because prices were too high. Okavango’s first full auction in November saw prices more in line with De Beers’s sight goods, possibly because the banks that finance the diamond trade had announced they would fund only 70% of rough purchases going forward, instead of 100% (Shor, 2013).

Okavango executives acknowledge that auctions can create short-term price volatility but insist that over the long term, auctions reflect market prices. Besides driving higher prices for its rough diamonds, the Botswana government is hoping the Okavango tenders will help supply the growing diamond-manufacturing industry around the capital city of Gaborone (Weldon and Shor, 2014). This would increase traffic of smaller and midsize diamond manufacturers into Botswana while boosting revenues (M. ter Haar, pers. comm., 2013).

Like De Beers, Alrosa and Rio Tinto still market most of their rough to specific clients in set-price sale contracts. Both companies have been auctioning their “specials”—rough diamonds larger than 10.8 carats—and very specific types of rough for more than a decade. Alrosa, mostly in conjunction with major trade shows where there is a concentration of diamond firms, sells about 25% of its production by value through such sales (figure 9). Through its Antwerp sales office, Rio Tinto sells about 10% of its production by value through auctions or tenders (Bain & Company, 2013).

A 280,000-carat pilot tender in December 2013, consisting of mainly lower-quality material, was deemed a success by Zimbabwe’s government and the AWDC, which led to the scheduling of a second sale in February 2014. While that tender in Antwerp exceeded 960,000 carats, the licensed producers have continued to hold separate tenders in Dubai and Zimbabwe while also providing goods for the Antwerp sales (Shor, 2014).

THE TENDER DEBATE

In the fall of 2013, a resurgence of prices at the tenders and auctions, while polished prices remained soft, prompted the International Diamond Manufacturers Association (IDMA) to ask that mining companies allocate “reasonably large amounts” of their goods for sale outside of the tender system (Robinson, 2014). The IDMA blamed such sales for the speculation that has further reduced industry profits, except at the mining level.The IDMA complained that the system was especially hard on the small and medium-sized companies that comprise the bulk of its membership. These firms did not have the financial muscle to compete with larger companies, which often push prices beyond an affordable range. IDMA members added that tender sales made it difficult to plan for the long term and fulfill their customer needs because they could not be assured of a consistent supply of rough diamonds. IDMA further argued that producers might benefit from high prices in the short run, but in the long run a healthy diamond market is in their best interest as well.

By late 2014, nearly every diamond mining company was conducting either a portion or all of its sales by tender and auction. An estimated 30% of world diamond production was sold by tender and auction events, compared to almost none a decade earlier. This was despite the fact that Dominion Resources, which acquired BHP’s diamond operations at the end of 2012, reverted to the set-price model (R. Platt, pers. comm., 2013). In mid-2014, however, the company reported that it planned to resume tenders for a small portion of its production to monitor market prices. The major producers such as De Beers, Alrosa, and Rio Tinto have adopted a mixed model that allows them to reap the steady cash flow from contracted set-price sales while adjusting prices (mainly upward) based on the results of their auction sales (“Times are changing,” 2013).

Lukoil, a new Russian producer that owns a majority stake in the Grib diamond deposit in the Arkhangelsk region adjoining Finland, began selling its production at auction in Antwerp in the fall of 2014. The sales were operated by several former BHP executives using the ascending clock format that had characterized most of that company’s rough sales until the end of 2012 (Miller, 2014).

While tender and auction sales still comprise a minority of rough sold into the market, they have become the driving force of rough prices. Nearly all diamond producers, including De Beers, apply the results of their own tenders or auctions to the rough prices at their traditional sights. As one analyst explained, De Beers’s use of the tenders means that, in effect, the prices realized at these sales influence the pricing for 40% of total diamond production by value. Likewise, Alrosa tenders a small percentage of its run-of-mine production to gauge price levels, and this influences the prices for the goods it sells by contract sales (Wyndham, 2013; M. ter Haar, pers. comm., 2013).

PRICE VOLATILITY AND ITS EFFECT ON THE MARKET

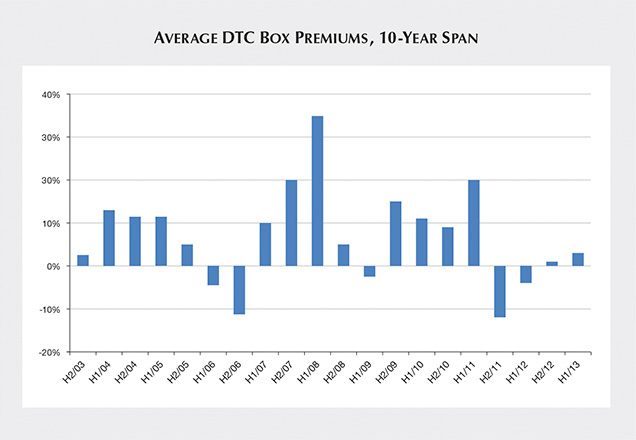

While the debate over the effect on rough prices continues, proponents still argue that, speculation aside, tender sales more accurately reflect prevailing market prices. Opponents maintain that the stability afforded by the sight system is necessary for a healthy diamond market. But as figure 10 shows, rough diamond prices over the past decade were stable only at the sources: De Beers, Alrosa, and Rio Tinto. In the secondary rough market, where the rest of the players operated, volatility was high. The chart, which lists average premiums De Beers sightholders got for selling their sight goods to diamond manufacturers, shows fluctuation between +13% and –11% between the second half of 2003 and the second half of 2006, well before tender/auction sales had a pronounced effect on the market. Of particular note is the 35% premium during the first half of 2008. The extraordinary events of 2008, after BHP Billiton’s full conversion to the tender auction system, touched off a credit-fueled speculative bubble, mainly on larger goods, that drove prices of both rough and polished to unprecedented highs just before the late-year economic crisis (Even-Zohar, 2009b). After the crash, prices fell to a 2.5% deficit one year later.

By 2010, bank financing was fueling a speculative boom in both rough and polished prices. Much of this boom was caused by a practice later dubbed “round-tripping,” in which some Indian diamond manufacturers secured higher credit lines by inflating export totals by as much as three to four times to make it appear their business was growing at that rate (Golan, 2012).

In the second half of 2011 (again, see figure 6), rough prices abruptly declined. The catalyst that broke the bubble was disappointing economic news from the United States, which caused banks to issue their first round of credit tightening. The Indian government announced it would impose a 2% duty on polished diamond imports to discourage round-tripping (Golan, 2012).

How volatile these prices would have been under the De Beers–dominated sight system is open to debate. Evidence shows that during difficult economic circumstances, the company reduced sales volume in an effort to maintain rough prices. As noted earlier, price stability at the primary (i.e., sightholder) level did not always carry over to the secondary rough market or the polished market, both of which showed high volatility during the early 1980s, when commodity markets crashed after a bubble, and in the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s.

Looking back on the 2013 results, De Beers CEO Philippe Mellier said the company had no plans to increase the percentage it sells through auctions (pers. comm., 2014) but noted that its sales allowed many newcomers and nonsightholders the opportunity to purchase rough diamond directly from a producer. He said that several customers were named sightholders in 2012 based on their participation in De Beers auctions. Between its direct auction sales and indirect sales through Okavango, De Beers is, ironically, the largest seller of rough at auction and tender, with an estimated total of 5.75 million carats in 2013 (Anglo American Corp., 2013).

CONCLUSION

The diamond industry is in the midst of numerous transitions as it moves from single-source to multichannel supply, with more pressure from governments, regulatory agencies, and financial institutions, in addition to the trend toward tender and auction sales. There is general agreement that the evolution to tender/auction sales of rough diamonds has caused considerable price volatility at the producer level, particularly as the shift occurred during one of the most turbulent economic periods in recent history. Yet volatility has always been a part of the secondary rough market, reflected in the premiums that De Beers sightholders received for their goods, so the true effect may not be fully apparent until the world economy is on a surer footing and the industry has adjusted to stricter banking policies. It is reasonable to conclude that tender sales have considerably widened the quantity and selections of rough available to smaller diamond manufacturers (figure 11), because the purchase requirements are lower and the application processes are less complex (and less expensive) compared to traditional sight contracts. It is certain that rough diamond tenders and auctions, combined with these other forces, will continue to influence how these goods are priced and traded in the coming years.

among those auctioned at Fusion Alternatives’ November 2014 sale in Antwerp. Photo

by Robert Weldon/GIA.