Botswana’s Scintillating Moment

ABSTRACT

While South Africa’s Nelson Mandela inspired the world with his vision of forgiveness and racial harmony, leaders in neighboring Botswana long ago sowed the seeds of cooperation and economic development. They also demonstrated a clear understanding of how to harness the country’s natural resources—diamonds, primarily—for the good of its people. Botswana has now taken a bold step forward with a long-term plan for value-added industries that will keep the country vibrant long after its diamond reserves are spent. While Botswana’s aspirations of becoming a major diamond center are great, so too are the challenges that lie ahead.

But the die has been cast, and both De Beers and its parent company, Anglo American, have highlighted the positive aspects of the move. De Beers Group CEO Philippe Mellier (figure 3) says the efforts underscore the company’s commitment to beneficiation. “As we make this move, Africa is once again at the forefront as De Beers and its partners lead the diamond industry into a sparkling new chapter in its illustrious history,” Mellier noted (De Beers, 2013a). He added, “Africa was home to the diamond industry when it began in the late 19th century, and De Beers and its partners were central to that growth.”

CHANGES DOWNSTREAM

The changes have required De Beers’s 82 sightholders and their associates to alter their habits and travel schedules. Sightholders have begun to make the 10 treks a year to Gaborone instead of London (figure 4). Reports from the first DTC Botswana sight in November 2013 were largely positive, despite initial grumbling and some logistical challenges (Bates, 2013). For example, there are currently no direct flights to Gaborone from the United States, Asia, or Europe. The dearth of banking infrastructure, Internet service, hotels, restaurants that will accommodate special dietary considerations, taxis, theaters, and other amenities that sightholders were accustomed to in London is not making the transition easy. These challenges will have to be worked out over time.“In a sense, this is exactly what it’s all about,” explains Kago Mmopi, communications and corporate affairs manager at DTC Botswana (figure 5). “Botswana is a developing country, and infrastructure is also developing, and needs to develop further. The move is inspiring the Batswana to do that. We have been speaking to local businessmen and alerting them of many opportunities that lie ahead. We also know that we need to fast-track this area.”

The government is also pushing hard to create state-of-the-art infrastructure to facilitate diamond trading in Botswana. Jacob Thamage (figure 6) is the coordinator of the Diamond Innovation Hub, an organization set up in part by the government to coordinate banking, security, and transportation for the diamond business, as well as to address the concerns of De Beers sightholders. But it also hopes to seize the opportunities that will arise for new diamond manufacturers in Botswana and the attendant businesses that will begin to grow as the diamond sector expands.

“A lot of our youth have come into the diamond business and excelled, and that has been a pleasant surprise,” explains Thamage. “But as we all know, it is an expensive industry that requires a lot of cash. The schemes we have in terms of funding our youth are not enough now for them to be able to buy diamonds for themselves. What we hope to see, as a beginning, is that a lot of those workers will someday open an office, just like this one, become diamantaires, and start contract polishing.”

Growth in African manufacturing, however small, is not going unnoticed in other cutting centers. The Hindu Business Line cited beneficiation programs in Africa as one of the reasons why the Indian market is “losing its sparkle” (Ashok, 2013).

Those concerns are premature, given Botswana’s minor role in manufacturing. What the country needs is a critical mass of talent, manufacturing efficiencies, and an infrastructure that supports a cutting industry. For consumers of such goods, inevitable questions arise: Are the diamonds well cut? Is there an understanding of proper yield? Can African labor costs compete with those of India? Can the world do business in Africa? Will consumers around the world, heeding a call to contribute to beneficiation in Africa, demand diamonds that are both mined and cut there? To illuminate these questions requires a basic understanding of the country, its people, and its diamond richness (figure 8).

BOTSWANA’S DIAMOND BUSINESS

Botswana remains a landlocked, sparsely populated territory comprising some 600,000 square kilometers, composed chiefly of arid savannah (figure 9). What Botswana lacks in agricultural capacity it makes up for with the world’s richest diamond reserves and production—four major mines and other deposits identified through exploration—as well as a relatively stable democratic government, and a hardworking, well-educated population. Its 2013 GDP per capita of approximately $16,400 is among the highest on the continent and closing in on neighboring South Africa’s, which is declining (CIA World Factbook, 2013).

Khama’s foresight appears particularly prescient today. Following his inauguration, he proposed the controversial 1967 Mineral Rights Act, aimed at vesting all mineral resources in the central government rather than in the hands of tribal leaders. Khama’s delicate negotiations, and his appeal for tribal elders to consider the good of the nation rather than the good of the tribe, ultimately led to passage of the act. His skills as a negotiator and leader were now cemented (Alfaro et al., 2005). This agreement, as well as a progressive and open attitude toward foreign investment, would lay the foundation for Botswana’s extraordinary growth, and ultimately for future negotiations with De Beers.

No other mining groups existed in Botswana. In 1968, a jointly owned company called Debswana (85% owned by De Beers and 15% by the government) was formed. For Khama and the democratic rulers who succeeded him, Debswana became the model for Botswana’s negotiations with other diamond and metal mining companies. By 1975, the discovery of additional diamond-rich pipes—such as the spectacular Jwaneng deposit—truly changed the equation. Two decades later, Botswana had become the most important diamond producer, supplying one quarter of the world’s diamonds by value (Janse, 1996). Although the government could have chosen to nationalize the mines, as neighboring countries were doing (Alfaro et al., 2005), Botswana’s leadership chose to negotiate terms that were extremely favorable to the country while acknowledging that it lacked the capacity to build the mining operations. Renegotiation with De Beers in 1969 led to a new agreement, essentially resulting in fifty-fifty joint ownership (Hazelton, 2002). That, combined with revenues from taxation of its resources, has given Botswana the lion’s share of the profits from diamond mining. Conversely, for De Beers, Botswana became a sort of insurance policy against growing competitors, particularly in Russia and Australia (Shor, 1990).

As much as the partnership between government and private enterprise has been lauded, it has also faced opposition. Critics contend that the partnership is too lopsided to be efficient and suggest that in recent economic downturns, as in the mining contraction of 2009 and 2010, many Batswana have been left without a safety net. Diversification of the economy and less reliance on a single “cash crop” would serve as a hedge against downturns, it is believed, particularly as diamond mining reaches an end in Botswana. Some suggest that the partnership is in fact counterproductive, for that very reason. “The…relationship serves as a disincentive to economic diversification and political accountability,” wrote Kenneth Good, an Australian professor in global studies at the University of Botswana who was expelled from the country in 2005 for writing a book critical of its politics (van Wyk, 2009).

The relationship has not always been smooth, and some historians note that Botswana has struggled, at times contentiously, to diversify its economy and to make De Beers its partner in the manufacturing aspect of the diamond business as well. According to industry journalist Chaim Even-Zohar (2007), De Beers was initially against bringing facilities to Botswana. Even-Zohar notes that the company “did everything in its power to prevent the establishment of more than two or three token manufacturing units.”

Shortly before the Jwaneng contract renewal, President Festus Mogae (1998–2008) expressed his country’s objective: “We are looking for some improvement in the sharing of benefit. The resource is ours, which is very important, but the investor is also entitled to a fair return” (Idex, 2004). Clearly much has changed since 2006, when the new agreements came into play. Today, beneficiation is a word that ostensibly holds equal weight with De Beers and Botswana. Mellier often singles out Botswana in speeches dealing with the company’s portfolio, noting the country’s role as a manufacturer and its rising profile as a rough diamond trading destination (Mellier, 2014).

Seretse Khama and subsequent presidents have all played significant roles in harnessing the country’s natural wealth and building institutions of good governance, education (the current literacy rate is almost 85%), and anticorruption. As in several preceding years, Botswana was rated the least corrupt African country in 2013 by Transparency International. But it was not only the rich diamond reserves that affected Botswana’s destiny; more recently, copper, gold, nickel, uranium, and other resources have been discovered. A focus on bolstering secondary and higher education, and a commitment to steering the economy away from total dependence on diamond revenue, began in earnest in 2008, when Ian Khama was voted into office. The fruits of an educated populace, good governance, and skillful negotiation for the extraction of its wealthy natural resources—particularly diamonds—have kept Botswana on track as one of the world’s fastest-growing countries, averaging 10% annual growth for almost three decades (Sanchez, 2006; Farah, 2013; figure 11).

From the late 1970s into the early 21st century, well over half of the country’s GDP was from diamonds, but a consistent policy to make the country less dependent on mining has emerged. In 2013, the diamond business alone—not counting copper, nickel and gold, or other industries—contributed to over a third of the country’s revenues. Over the years, Botswana has been lucrative for De Beers as well. In 2000 alone, over 80% of the company’s revenue came from its Botswana portfolio—53% of that from the Jwaneng mine alone (Even-Zohar, 2002). For De Beers, reliance on Botswana’s riches—and some might argue overreliance—is also evident.

Of course, there are still enormous challenges Botswana must contend with. In the 1990s, the scourge of HIV/AIDS virus hit hard in the sub-Saharan country (Weldon, 2001). Today, approximately 24% of the population is infected with the virus, according to the World Health Organization. Botswana’s relatively tiny population and workforce can ill afford such a devastating blow. Nevertheless, Botswana’s leaders have met the challenge with education programs on HIV prevention, partnerships and grants with pharmaceutical companies such as Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the construction of hospitals and treatment centers. Grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are aimed at managing the symptoms of the disease or preventing its progression. Over 80% of Batswana infected with HIV/AIDS are covered by free antiretroviral medication, and 100% have access to it. President Quett Masire (1980–1998) was the first Batswana leader to face the problem at the turn of the century, and in 2009 he declared it a national imperative to wipe out the disease. He established 2016 as the target year when no new infections would occur. In 2011 alone, the Botswana government spent some $385.5 million on AIDS prevention, care, and treatment, with a special focus on children stricken with AIDS or orphaned by the disease. The results have been dramatic in terms of life expectancy through earlier detection and treatment, and reductions of HIV transmission from mother to child (figure 12). In 2012, President Khama noted in a state of the nation address that the country was on track to achieve a less than 1% transmission from mother to child by 2015. Botswana’s example has been lauded throughout Africa and the rest of the world. The expenditures “come at a considerable cost,” according to Khama, though they are universally considered utterly necessary for Botswana to move forward economically and socially.

In 2012, De Beers produced less than 30 million carats worldwide—another year of retrenchment from a high of 34 million carats in 2006—due mainly to flagging global diamond demand, a lingering after-effect of the 2008 global recession. The following year saw major changes at the sources, such as the sale of the Finsch mine and a slope failure at Jwaneng (Greve, 2013). Liquidity problems for many Indian manufacturers, which still cut most of Botswana’s diamonds, also slowed the momentum. For Debswana, a company dedicated to addressing safety concerns, it was also a difficult year. The slope failure at Jwaneng in June 2012 killed an employee, and investigations into its cause shuttered the mine for several months. Debswana has since taken an even more aggressive stance on safety, promulgating a “zero harm culture” while improving its production figures (Gowans, pers. comm., 2013).

In tandem with declining production, 2012 sales totaled $5.5 billion, a billion less than 2011 (De Beers, 2013b). Nevertheless, the goal of transferring De Beers’s sales arm to Botswana was accomplished in 2013. The business lull may have been advantageous by allowing a more gradual buildup of Gaborone as a diamond sorting, valuing, and selling center. Debswana is poised for growth, particularly as new diamond customers emerge in India, China, and other developing markets. De Beers estimates 5% growth in China, Hong Kong, and India by 2017, while the U.S. market—which now represents over a third of global diamond sales—will slip by about a third of its present portion.

“Beyond mining, the creation of long-term, value-added products, training, and employment for Botswana is beginning to take effect, though there is still a ways to go,” says Pauline Paledi, the executive director of the Botswana Diamond Manufacturers Association (figure 13). The organization, established in 2007, consists of some 17 full members who actually manufacture diamonds in the country today, plus recent applications for an additional four members at the time of this writing. The association lobbies the Botswana government “as a single voice,” explains Paledi, and works out compliance matters regarding labor laws and visa and residency issues for foreign manufacturing companies. The goal is to attract more foreign investment, and eventually homegrown diamond manufacturing as well. “We see growth ahead,” says Paledi. “The market is getting stronger for manufacturing, and it is diversified, as we can all see.”

DIAMOND MINES OF BOTSWANA

From Gaborone, a car can reach the front gate of Jwaneng, the world’s richest diamond mine, in about two and a half hours, a ride straight through a desolate, hilly region of savannah and occasional cattle ranches. For those lucky enough to receive an invitation to visit the mine and proceed through security checks and briefings, the overwhelming desire is to peer over the edge into this open pit, a gigantic manmade hole visible from outer space (figure 14).Jwaneng—whose name means “place of small stones” in Setswana—was discovered in 1973. The pit currently descends nearly 400 meters into three separate kimberlite pipes. It is expected to reach almost 700 meters in depth by 2017, as new cuts dig into the kimberlitic ore in the search for diamonds. The latest is Cut 8, which extends laterally into the kimberlite pipes at Jwaneng and is expected to produce over 100 million carats and extend the life of the mine until 2028. A bird’s-eye view of this massive removal of earth reveals the rugged face of Botswana’s principal mine by value, which has the capacity to produce some 2.5 million carats of diamond on a monthly basis. During the recession, and because of the 2012 slope failure, production dropped to about half of that (Mmopi, pers. comm., 2013). Once fully operational, Cut 8 will transform Jwaneng into one of the world’s super-pit mines.

Jwaneng employs over 2,500 people, though they are rarely visible, partly due to the pit’s immense size and partly for security and safety reasons. Cut 8 is expected to expand the workforce by at least 50%. At the bottom of the pit, kimberlitic ore is broken up through dynamite blasting on a regular basis. Miners are also busy maneuvering the massive Komatsu 930 trucks, each the size of a house and designed to cart out 250 tons of kimberlitic ore per haul (figure 15). A staggering 60 million tons of earth are thus removed in a high production year; on any given workday, traffic from the trucks forms a constant stream into and out of the mine. Where the earth goes after processing is another logistical and engineering feat.

First, the ore is crushed into much smaller particles at a plant on the surface. The clay and mud are removed, and the diamonds are separated from the ore by X-ray at a completely automated recovery plant (CARP) where, as a theft countermeasure, no human hands touch the ore. After that, the diamonds are presorted, cleaned, and packaged using laser technology (again with no hands touching the rough). The diamonds are then ready for transport to Gaborone for sorting and valuing, and ultimately for sale. The rough is classified by weight, shape, clarity, and color, regardless of source. According to Kago Mmopi, Debswana’s mines alone supply between 200,000 and 500,000 carats to DTC Botswana on a weekly basis (figure 16).

Botswana’s other diamond mines are independently owned rather than joint ventures between De Beers and the government. One of these is the Lerala mine, owned by DiamonEx, which has been stalled due to restructuring and is expected to reopen in 2014. Others such as the Karowe mine, operated by Lucara Diamond Corporation, are selling diamonds through auctions. Karowe made news by yielding 26,196 carats for auction (“Lucara completes first sale of Botswana diamonds,” 2012) and announcing the find of a 4.77 ct blue diamond as well as several large diamonds (Golan, 2013). Auctions are also the government’s preferred method of selling diamonds, at least for now.

THE OKAVANGO DIAMOND COMPANY: THE MARKET EXPERIMENT

De Beers was traditionally the sole purchaser of diamonds mined in Botswana. A renegotiation in September 2011 changed that, with the government obtaining the right to purchase a progressive 10–15% allotment of the rough to sell through its own channels over the next few years. To that end, the government established the ODC (figure 17) in 2012 and appointed Toby Frears as its managing director that same year.

The 10%-plus that the ODC buys on a weekly basis is gathered and sold to clients around the world via auction. Sales occur about 10 times a year and include parcels and single stones 10 ct or larger. It is thus a different system from the fixed allocation contracts implemented by De Beers and its sightholders. As would be expected, ODC clients must be properly vetted and comply with strict guidelines to register and qualify as buyers. Details about each company’s role in the diamond value chain, top personnel, and compliance with all diamond sector regulations are required by ODC.

For all its advantages, the auction system tends to be risky: volatile during good economic times, and slow to nonproductive during bearish economies. Under such conditions, fixed contracts make it easier to fine-tune and control the market. Marcus Terhaar (figure 18), ODC’s deputy managing director, explains that the auctions help the government derive current market value for the products.

ODC officials seem open to the idea of a dual selling system that incorporates both ideologies. “A lot of companies use dual systems—meaning that they have options and contracts. That tends to mitigate the risk,” Thamage explains. “By the middle of 2014, we will have completed a full cycle of selling and understood the possibilities of auctions and contracts.”

Terhaar highlights the beneficiation aspects that are already taking place through the ODC: “What we have in Botswana, insofar as the diamond sector is concerned, is a very strong diamond mining industry. We have a very well-established sorting and valuing operation in Debswana, and we have a good five to seven years into diamond manufacturing. Rough trading is clearly the missing link for Botswana, and that is the primary focus of the ODC. It will bring jobs. This means that 150 people are coming to our premises every five weeks or so. That means 150 more hotel accommodations, 150 more seats on local airlines, and 150 more customers looking for taxis, making dinner reservations at restaurants. It will foster the growth of ancillary services: diamond reports, banking, rough valuing, and marketing services, and so many other types of related services.”

For now, ODC is busy establishing its operation, conducting sales, and promoting itself as a viable separate channel for rough diamond buying. “This is a big feather in Botswana’s cap,” says Terhaar. “Ten years ago this was all bush country. Botswana has proven that it can be done. And while there is a lot of learning to capture, there is certainly the motivation, and the will, for Botswana to perform as a benchmark diamond center—as efficiently as Antwerp, Israel, or any other diamond center in the world.”

CAN A CUTTING INDUSTRY BE SUSTAINED IN BOTSWANA?

While Botswana prospered by carefully redirecting its diamond wealth into nation-building, establishing a domestic diamond manufacturing industry remained an elusive goal until recently. Neighboring South Africa benefited from a well-established diamond cutting industry that employed several thousand workers. Even so, much of this industry survived because De Beers subsidized local cutting operations by providing rough at a 10% discount (actually sparing buyers export taxes on rough). Some of these operations existed mainly as a means for their owners to obtain rough allocations from De Beers. They performed minimal work on stones in the local plants before exporting them to Israel, Antwerp, or India for actual manufacturing (Shor, 1990; figure 19).

De Beers’s opposition began to crumble in 1990 when the company entered negotiations to renew its five-year contract with the government to sell rough mined by Debswana. With De Beers owning 50% of Debswana, such contracts would seem to be a routine matter, but in 1989 the government had raised the issue of starting a domestic manufacturing operation. At the same time, a number of major rough diamond dealers were lobbying Botswana’s parliament to sell 20% of the company’s production outside De Beers’s network, claiming they would be willing to pay 5–7% higher prices than De Beers. One of those dealers, Maurice Tempelsman of Lazare Kaplan International (LKI), offered to build a polishing factory if the government was willing to supply diamonds to the operation (Shor, 1990). The government made no such promise, but LKI built the factory anyway.

De Beers, which already employed 5,000 workers at its three mines in Botswana, eventually agreed to develop a cutting factory, mainly to forestall the parliament from considering this 20% “market window” (Shor, 1990). The operation, named Teemane, opened in 1993, but a decade later only three others had been built, the largest being the Lazare Kaplan International operation (J. Thamage, pers. comm., 2013).

Botswana assumed a much greater role in De Beers’s operations after 2001 when, as part of the company’s reorganization, it assumed a 15% stake in the firm’s ownership. Botswana also captured a much greater strategic role after De Beers began phasing out its agreement with Alrosa, the Russian diamond mining company, to market its production—accounting for about 25% of De Beers’s rough sales—and sold off its aging South African mines and its $5 billion diamond stockpile (Even-Zohar, 2007). By 2005, Botswana was by far the largest and most profitable part of De Beers’s operations, accounting for 70% of its earnings (Grynberg, 2013). This fact was not lost on the country’s leadership, which leveraged an aggressive series of beneficiation measures in its negotiations for both the sales contract with Debswana and the renewal of the 25-year lease at Jwaneng (Even-Zohar, 2007).

The agreements, reached in 2006, covered a thousand pages but contained three main requirements that would transform operations for both sides:

- De Beers would directly supply local firms that qualified for a diamond manufacturing license.

- De Beers would relocate all of its sorting and rough sales operations from London to Gaborone by 2009.

- A certain percentage of De Beers sight goods would be reserved for local polishing operations.

While the 2006 agreement provided for supplies to 10 factories, as selected by De Beers, Botswana moved aggressively beyond De Beers’s plans and issued licenses to 16 companies, which began taking rough supplies through separate sights domestically in January 2007. By fall of that year, six had gone into production (Golan, 2007). On the second point, the 2008–2009 world financial crisis hit De Beers hard, requiring the company to borrow $500 million from shareholders (including $200 million from the Oppenheimer Trust, which owned 40% of the company). The crisis also forced De Beers to postpone its relocation plans until 2013 (Krawitz, 2008; Anglo American, 2009).

In 2008, in preparation for De Beers’s arrival and the growth of a domestic cutting industry, the diamond industry, led by South African manufacturer Safdico with the Botswanan government’s cooperation, commissioned the Diamond Technology Park. The secure 35,000-square-meter facility was located next to the new De Beers building and just four kilometers from Sir Seretse Khama International Airport. It was designed to house about 15 medium-size manufacturing operations in two buildings, plus industry services such as banking, manufacturing equipment, and diamond grading—GIA’s Gaborone laboratory was one of the first tenants—in a third building. The Diamond Technology Park website notes that by 2012, these operations had outgrown the complex, causing a number of manufacturers to locate in the industrial parks nearby.

Statistics for 2013 indicate that Botswana’s drive to create a local diamond manufacturing industry has been a success. More than 3,000 workers are employed in polishing operations (compared to fewer than 500 in 2006) and several thousand more through ancillary businesses serving the diamond sector. Polished diamond exports neared $800 million and were forecast to top $1 billion by 2015, compared to $100 million in 2008. The Diamond Technology Park was fully rented, and the government commissioned plans for a fourth building of 4,000 square meters to be completed by the end of 2014 (Grynberg, 2013; Shor, 2013). By the end of 2013, 24 manufacturers were operating in Botswana, 21 of them receiving rough from Debswana through local sights (figure 20).

MANUFACTURING COSTS

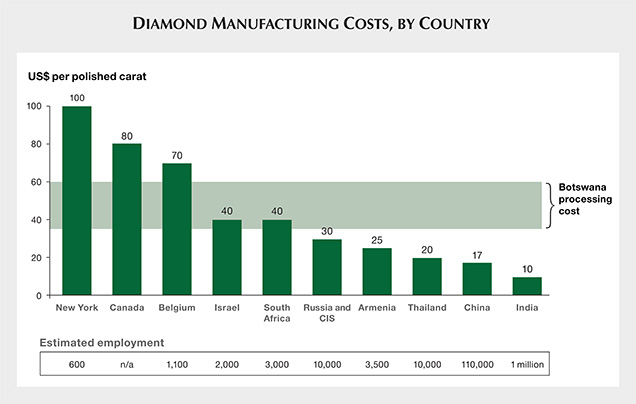

Diamond manufacturing costs in Botswana range from just under $40 to $60 per carat, depending on the efficiency and technological capabilities of a given operation. These costs include labor, utilities, maintenance and technology support, and transportation. This cost range is much lower than Canada’s ($80 per carat) but still more than double that of China ($17 per carat) and four to six times that of India ($10 per carat), which polishes 92% of world production by volume (Gregorian, 2013; figure 21).

Labor costs are less of an issue with Safdico and Diacore Botswana (formerly Steinmetz), which specialize in large, high-quality diamonds. Both companies have developed rigorous training programs because each diamond must meet very high, exacting standards. Safdico and Diacore both added that they are in Botswana for the long term (K. Teichman and R. Moses, pers. comms., 2013).

The government has been diligently auditing companies to ensure that diamond factories provide full training and employ Batswana to perform all of the work necessary to produce finished stones (R. Moses, pers. comm., 2013). Diamond executives give the government high marks for introducing regulations and policies that support equipment imports, funds transfer, building licenses, and transparency.

Several diamond firms have taken their beneficiation role beyond offering training and employment to local workers. Safdico supports programs that train computer technicians, schoolteachers, and other community-building professionals in villages outside the capital. Diacore Botswana provides microloans to employees for school fees and conducts events for community improvement projects. They have also supported sporting events and employ prominent local athletes (figure 24).

Executives of manufacturing facilities in Botswana, while acknowledging the economics and challenges, are divided over whether the country’s diamond industry can become fully self-sufficient. But even the most skeptical see significant potential for improving Botswana’s competitive position so that it may become a successful niche producer, like New York or Antwerp. “It is still early days, initial stages,” said Erik van Pul, manager of Eurostar in Botswana. “We are seeing improvements all the time as workers gain more expertise and government services and infrastructure improves.”

In 2010, for example, most Botswana diamond operations could not profitably produce polished diamonds below one carat because training and high-tech processing equipment were not fully in place. By 2012, the more advanced operations were producing 0.40 ct stones—at a profit, according to van Pul. At least 10 factories were producing precision “triple-excellent” cuts comparable to any diamond polishing operation in the world. While that represents true progress, one analyst believes that the ability to polish melee (0.10–0.20 ct) profitably is necessary to create a manufacturing industry that sustains large-scale employment (M. van den Brande, pers. comm., 2013).

THE FUTURE

The year 2027 is the government’s benchmark for developing a diamond-polishing industry that does not depend on domestic rough (figure 25). Jwaneng is scheduled to be redeveloped into an underground mine that same year, which will sharply reduce production. By comparison, Australia’s Argyle mine fell from a peak annual output of 42 million carats as an open pit to 20 million carats as an underground mine (Argyle Diamond Mine, 2013). Production will likely continue 30 to 40 years beyond this date, but with much smaller volume and higher cost.

Indeed, one World Bank study (Grigorian, 2013) noted that “[diamond] producing countries hoping to establish a viable cutting industry are squeezed by competition from two directions: one from low-cost economies such as India and China, another from high-skills economies such as the United States, Belgium, Israel, and Canada. For any latecomer, the challenge is plain: Either be cheaper (and work harder) than the former, or be more knowledgeable and skills-intensive than the latter.” The way through this competition, the study concluded, was for these countries to achieve a manufacturing niche by branding to provide added value to their products.

It remains to be seen whether Botswana-branded cut diamonds will captivate consumer attention globally. Buyers are increasingly conscious of the products they purchase and the supply chain involved. The storyline for a Botswana brand is undoubtedly strong. Consumers, drawn to African diamonds for well over a century, could find assurance in knowing that the diamonds they purchase today have contributed to skills transfer in Africa, poverty alleviation, and the dignity of employment for Botswana’s people.