Tsavorite Garnet and Mahenge Red Spinel

At GJX, Daniel Assaf (The Tsavorite Factory, New York City; figure 1) explained the current market situation for tsavorite garnet, Tanzanian red to pink spinel, and yellow danburite. According to Assaf, the recent recession and the ensuing disruption in supply had less of an impact on his business than increasing demand from China. For him, current rough scarcity and high prices relate more to the growth in the Chinese jewelry market, which 5 to 10 years ago was a fraction of its size today.

Assaf explained that both tsavorite and spinel are rare stones, and even minor changes in the market might have a considerable impact. If just a fraction of one percent of Chinese consumers becomes interested in tsavorite, this has a measurable consequence for supply, especially if production in mining areas is static or even showing slight declines. According to Assaf, the biggest tsavorite purchasers at the source in Arusha, Tanzania, are Sri Lankans buying for the Chinese domestic market. These buyers are prepared to pay very high prices for tsavorite rough.

To illustrate the sporadic nature of current supply, Assaf cited a bright, light-toned green grossular garnet. This material has become popular and is sold as “Merelani mint” garnet. It is usually recovered as a byproduct of tanzanite mining. Every so often, he related, miners find a productive pocket and buyers fly in within a couple of weeks.

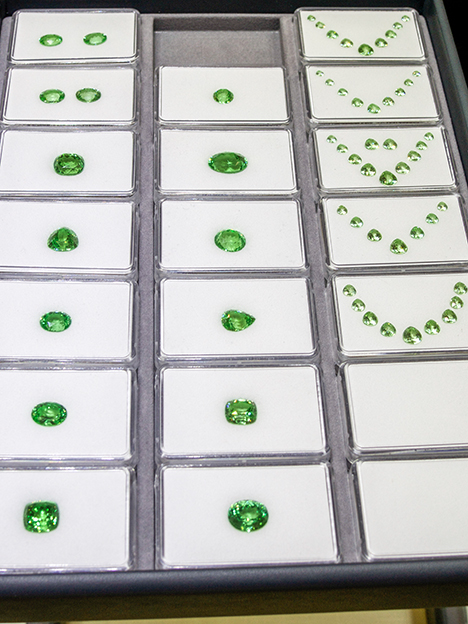

According to Assaf, the stones on the tray in front of us (figure 2) were from the latest small pocket and had been in the ground just a few months earlier. After the initial flurry of buying activity, Assaf said, it might be another year or two before a similar discovery. In the meantime, the miners might bring buyers the occasional stone—at much higher prices.

In Assaf’s opinion, today’s tsavorite rough prices in Arusha are almost “out of control.” In effect, there is a disconnect between the Arusha prices and the prices in Tucson, which will likely take several years to readjust.

His company stops buying before the Tucson show because the clientele here will not pay the high asking prices. He cited an instance several weeks earlier in which buyers were offering him top-quality rough for approximately $10,000 per stone, in sizes sufficient to cut 3 ct finished gems. A stone cut from this rough would have a per-carat price well above what the market at the Tucson show would pay. Besides the high asking price, Assaf said there is a significant element of risk in buying rough: “You never know what kind of unpleasant surprises you might find.”

He pointed out that there are places in the world where such high prices are accepted—China and possibly parts of Europe—which is why the few fine rough tsavorites that become available every month are snatched up. Assaf had just heard of a 7-gram piece of tsavorite—perhaps suitable for a 10 ct finished gem—that sold for $200,000 in Arusha.

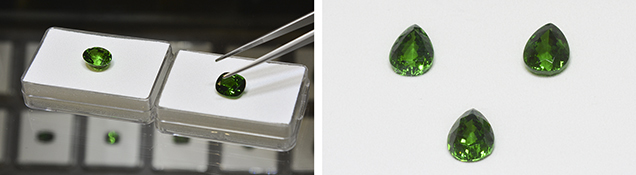

Assaf showed us two examples of the finest tsavorite colors. In his opinion, both are of equal merit (figure 3, left). Some clients love the deeper, darker color, while others prefer a brighter, lighter-toned green. In either case, he said, the most important consideration is to have a blue color component rather than a yellow one. As long as the gem is not overly dark, and has a bluish cast to the green, it is a quality stone. If it is pale but still has a bluish component to the green, he would classify it as a “mint” garnet.

We asked Assaf how recent Chinese demand has affected tsavorite prices. He said that for sizes under 2 ct, prices have increased as much as 30–40%. The impact has been most dramatic in larger stones: For gems larger than 3 ct, prices have tripled. He felt that prices for large tsavorites have gone up in relation to emerald and other gems due to scarcity of supply and high demand.

To emphasize the point, Assaf chose a suite of three tsavorite pear shapes totaling 37.79 carats (figure 3, right). Each gem was above 10 ct and of the highest clarity, so they constituted exceptionally rare material. Aside from these standouts, Assaf admitted he had few stones of such size—large stones are typically a Tsavorite Factory specialty—due to the prohibitively high price of rough. He lamented that with today’s stratospheric prices, he would have to pay around $200,000 to obtain another 7-gram piece to cut another 10 ct gem. And very few clients—likely none at this show—would accept the resultant high per-carat prices for the finished gem. That leaves two possibilities: Either the prices will adjust in Arusha, or they will become accepted in the U.S.

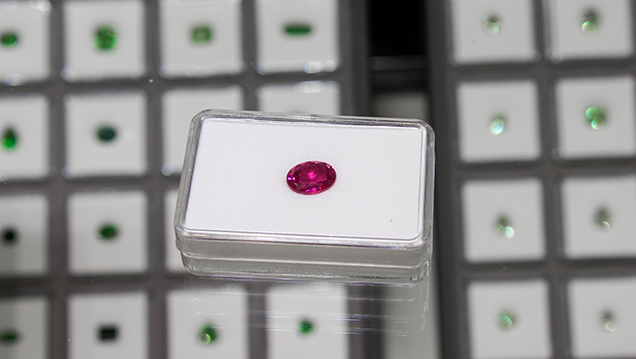

Assaf recounted that some of the same market factors apply to red spinel. His company does not carry spinel from Myanmar, focusing instead on Tanzanian material. This year, he said, a specific color people were calling “Mahenge”—deep pink with a touch of orange, almost like a “padparadscha” color—was in extremely high demand (figure 4). Assaf had sold all of his “Mahenge” spinel but none of the other colors. While these lavenders, blues, and mauves are quite beautiful and competitively priced at around 10% of the pinks, the red to pink spinels are what his clients seek. Assaf also mentioned that buyers looking for something unusual picked yellow danburite from Tanzania, and that this gem had sold quite well for him at the show (Summer 2008 GNI, pp. 169–171).